Charles Quest-Ritson: 'Gardens of supreme botanical importance are being degraded by new owners and changing priorities'

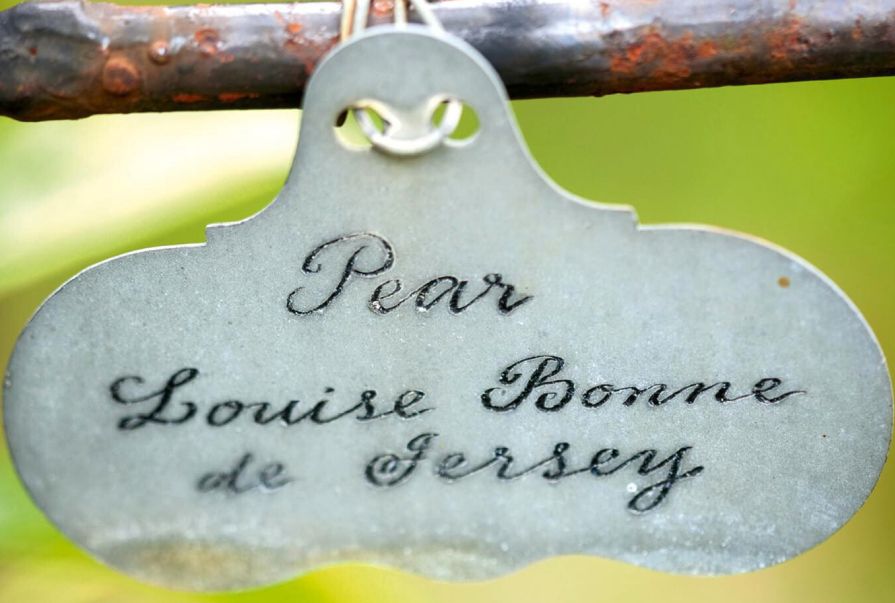

What's in a label? More than you might think, says Charles Quest-Ritson.

I was given my first ‘garden’ in a corner of my grand-parents’ apple orchard and that’s where I sowed the seeds we had bought at Woolworth’s. Then we labelled them, using pieces of white-painted wood (query — was that the norm in those days?), on which I used the gardener’s BB pencil to write their names in capital letters. Sowing the seeds was an act of faith because, later that year, they would turn into flowering plants. But labelling them was an act of ownership.

Labels and labelling are an essential part of gardening. There is nothing more disappointing than seeing a beautiful plant in someone else’s garden and not finding a label to tell you its name. Actually, that’s not quite true, because it’s just as bad when this happens in your own garden. It’s especially embarrassing if you have someone with you who asks the question, because owners are supposed to remember the name of everything in their garden. There are, however, situations where ignorance is excusable: if you buy lots of new bulbs — tulips or daffodils for example — that you haven’t grown before, you cannot be expected to remember their names as soon as they start to flower.

There are gardens, however, where the owners decide that labelling would contradict the spirit of the place that they have created. This is true of Ninfa, the magical Anglo-Italian garden in the Pontine Marshes south of Rome, where labels would detract from the otherworldly effect of wandering through the ruins of an abandoned medieval town where the walls are covered by climbing roses.

"I asked a gardener there if there were any plans to restore the labels. Her reply was that she had neither the time nor the funding for it"

Some years ago, too, in England, the then generalissimo of John Lewis decreed that all the labels at the group’s Longstock Water Garden in Hampshire should be removed. I think this was a mistake, however: Longstock is beautiful, but not in the ethereal way that Ninfa is. Labels would add greatly to the garden’s value — it was at Long-stock, years ago, that I first learned the names of all the best water-loving plants. Earlier this year, I asked a gardener there if there were any plans to restore the labels. Her reply was that she had neither the time nor the funding for it.

Plant labels are important. You won’t learn anything from visiting a plantsman’s garden unless the plants say what they are. Gardens that are open to the public have a special duty to get their labelling right. I feel cheated — not merely disappointed — if I visit a major educational garden and can’t find a label. Gardeners will tell you that labels get stolen, but that’s no excuse for failing to replace them. And they have to be clearly visible, too.

Go to the Savill Garden in Windsor Great Park for an exemplary display of comprehensive labelling. Every tree, shrub and group of herbaceous plants is correctly labelled and the label itself easily found in surely the best-managed woodland garden in Britain. On a par with the Savill, although very different in scale, is David Austin’s immaculately maintained rose garden at Albrighton in Shropshire. It is, of course, a show garden for the nursery, so everything must be correctly labelled, but the clear and extensive labelling adds immeasurably to the pleasure and value of a visit.

Labelling in the RHS’s gardens is a massive undertaking and very well managed. Over the past two years, staff have produced nearly 19,000 labels, with a further 3,000 in the pipeline. That said, the society considers it wise to remove the labels that mark some of its rarer snowdrops. For the same reason, some of its more valuable plants on display in the alpine house are held behind locked glass windows.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

We are lucky with the RHS, but, time and again, I find that gardens of supreme botanical importance are degraded as a result of changing priorities on the part of the new owners. Usually, this means increasing the footfall, which creates extra problems for the hard-pressed gardening staff. I am sorry for the great Hillier arboretum near where I live in Hampshire, which falls under the aegis of the county council. I don’t know how the on-staff botanists and horticulturists feel, but it is clear from walking in all but the most visited parts of this vast domain of mega importance that they are insufficiently supported by the council. When I pointed out recently that a label was missing from a fine rhododendron near Sir Harold Hillier’s home, Jermyn’s House, they were profuse in their thanks and replaced it immediately.

I still label my annuals, although I am now old enough to know what I have sown and where I put it. But I do miss those large, white-painted labels and our gardener’s BB pencil.

Charles Quest-Ritson wrote the RHS Encyclopedia of Roses

Credit: Getty Images

Charles Quest-Ritson: no chain, no gain — how using a chainsaw will improve your garden

Gardeners can be reluctant to take a blade to a healthy tree, but sometimes a severe pruning will leave both

Credit: Getty Images

Charles Quest-Ritson: 'I'm always amazed by the codswallop that garden experts write'

Charles Quest-Ritson takes aim at some of the gardening advice that constantly does the rounds despite being complete nonsense.

Charles Quest-Ritson: I hate almost all alliums — their colour is hideous, their smell is disgusting — but there's one I've fallen hopelessly in love with

Charles Quest-Ritson loves almost all flowers. And the emphasis this week is very much on 'almost'.

Charles Quest-Ritson: All gardening is habitat destruction, but gardens have a purpose — and rewilding is an absurd fantasy

The 19th century's hugely successful cultivation of plants on the once-barren Ascension Island has lessons for us today, says Charles

Charles Quest-Ritson is a historian and writer about plants and gardens. His books include The English Garden: A Social History; Gardens of Europe; and Ninfa: The Most Romantic Garden in the World. He is a great enthusiast for roses — he wrote the RHS Encyclopedia of Roses jointly with his wife Brigid and spent five years writing his definitive Climbing Roses of the World (descriptions of 1,6oo varieties!). Food is another passion: he was the first Englishman to qualify as an olive oil taster in accordance with EU norms. He has lectured in five languages and in all six continents except Antarctica, where he missed his chance when his son-in-law was Governor of the Falkland Islands.