Curious Questions: What is a garden hermit?

Martin Fone takes a look at the curious history of the hermits who spent years living happily in the grounds of country houses, perhaps the ultimate garden folly.

A garden gnome might well add a touch of whimsy to a corner of a modern garden but their origins are rooted in a darker and curious practice that fascinated the landowning classes in Georgian England. By the 18th century garden design in country estates had moved on from the highly stylised, geometric approach favoured by the continentals to a more naturalistic approach, espoused by the likes of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, even if the natural topography of the land had to be altered root and branch to achieve the effect.

Out went parterres with their forced formality and in came artfully-designed sweeping landscapes, romantic-looking lakes, shady bowers, and waterfalls. To complete the look of a long-lost Arcadia, temples, grottos, and follies were erected, often artificially aged and offering commanding views of the vista or areas of welcome seclusion.

A must-have feature was a hermitage, a roughly-constructed hut of a type that would appeal to someone who was more concerned with spiritual improvement than creature comforts. Made from brick or stone or, occasionally, from gnarled tree roots and branches, they were often decorated with shells or bones inside.

England’s first garden hermitage was built by William Stukeley at his home in Grantham in 1727, and inspired — as he claimed in a letter — by a druidic grove that hid ‘a cell or grotto…like those I have frequently seen in travels’. When he moved to a new estate in Stamford in 1730, he built another hermitage, this time sitting at the back of a druidic stone circle and decorated with sculptures and stained glass.

Another early example was built in the 1730s for Queen Charlotte of Ansbach, wife of George II. Consisting of an octagonal stone sanctuary stuffed with busts of great thinkers, doubtless to inspire lofty thoughts and provoke deep contemplation, it was described by one contemporary as ‘a heap of stones, thrown into an artful disorder, and curiously embellished with moss and shrubs, to represent rude nature’.

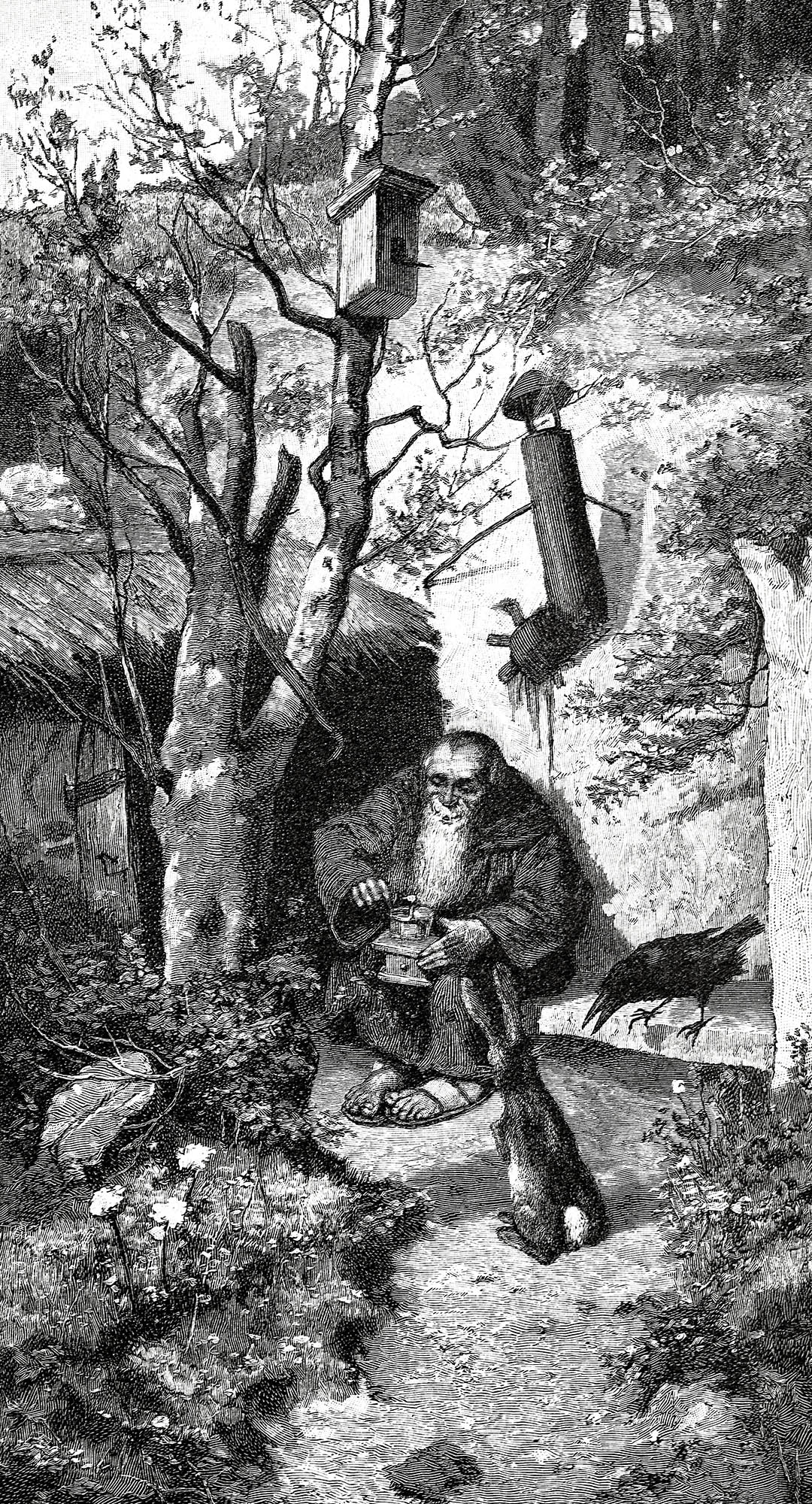

Charles Hamilton created a landscaped park at his home at Painshill near Cobham between 1738 and 1773. One of its features was a hermitage — one you can see to this day, thanks to the recreation that is pictured at the top of this page.

It did not meet with universal approval, Horace Walpole observing that ‘it was ridiculous to set aside a quarter of one’s garden to be melancholy in’, according to Edith Sitwell’s English Eccentrics (1933). Sitwell remarks that the hermitage was ‘remarkable more for its discomfort than its beauty’ consisting of ‘an upper apartment, supported in part by contorted legs and roots of trees, which formed the entrance to the cell’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Undeterred, Hamilton decided that what his hermitage needed was its own live-in hermit and set about recruiting one to meet his onerous and very specific requirements. The hermit must ‘continue in the hermitage seven years, where he should be provided with a Bible, optical glasses, a mat for his feet, a hassock for his pillow, an hour glass for his timepiece, water for his beverage, and food from the house. He must wear a camlet robe, and, never under any circumstances, must he cut his hair, beard, or nails, stray beyond the limits of Mr Hamilton’s grounds, or exchange one word with the servant’.

If he met these conditions, the hermit would receive the princely sum of £700. A man by the name of Remington secured the position but within three weeks he had been summarily dismissed, having been found having a drink in the local public house, so the story goes.

Near Preston a garden hermit with more endurance accepted the challenge of living underground without human contact for seven years in return for a stipend of £50 per annum for life. His subterranean accommodation was described as ‘commodious’ and included a cold bath, a chamber organ, as many books as he desired, and food from his employer’s table. He stuck it out for four years.

The most famous garden hermit was Father Francis who was accommodated on Richard Hill’s estate at Hawkstone in Shropshire in what was described in 1784 as a ‘well-designed little cottage’. Sensibly, Francis was only in residence during the summer months and was generally found, according to a contemporary report, ‘in a sitting posture, with a table before him, on which is a skull, the emblem of mortality, an hourglass, a book, and a pair of spectacles…he always rises up at the approach of strangers. He seems about ninety years of age yet has all his senses to admiration. He is tolerably conversant, and far from being impolite’.

Such a draw was he that the Hill family had to build their own public house, The Hawkstone Arms, to cater for all the visitors. Shropshire boasted another garden hermit, on Colonel Durant’s estate at Tong Castle, Carolus also known as Charles Evans, who was the subject of William Hobday’s now lost masterpiece, The Hermit of Tong, resplendent in hood and dark brown cowl.

Inevitably, the venerable Francis met his Maker and was replaced by an automaton, a move that was not without its critics, one visitor reporting that while ‘the face is natural enough, the figure [is] stiff and unnatural’. Samuel Hellier had used an automaton, said to move and give a lifelike impression, at his Staffordshire seat, the Wodehouse, near Wombourne.

Rather than employ a living hermit or make do with a model, in 1763 the naturalist Gilbert White persuaded his brother Henry, a parson, to pose as an ascetic sage at his Selborne estate for the amusement of his guests. One, a Miss Catherine Battie, was duly impressed, noting in her diary:

‘In the middle of tea we had a visit from the old Hermit. His appearance made me start. He sat some with us and then went away. After tea we went into the Woods…return’d to the Hermitage to see it by Lamp light. It look’d sweetly indeed. Never shall I forget the happiness of this day.’

Would-be hermits were also on the hunt for positions. One such was a Mr S Lawrence who placed a notice in the Courier on January 11, 1810, advising that ‘a young man, who wishes to retire from the world and live as a hermit, in a convenient spot in England, is willing to engage with any nobleman or gentleman who may be desirous of having one.’ Interested parties were requested to send details of gratuity and other particulars to an address in Plymouth. Whether Lawrence was successful in his search is not known.

In truth, though, relatively few landowners went to the trouble of hiring their own living, breathing garden hermit. While they undoubtedly added a touch of quirky eccentricity to a garden and, as the Hills discovered, could be a source of attraction for the burgeoning leisured classes, even by the standards of the time there was something demeaning and exploitative about the idea. While Gordon Campbell identifies over a hundred hermitages in his book, The Hermit in the Garden (2013), the vast majority were either unoccupied, offering a place for quiet contemplation, or furnished with sufficient paraphernalia associated with a hermit to suggest that he had stepped out for a while.

By the early 19th century, the craze for human garden hermits had been consigned to the footnotes of social history. Those who wanted to add a sense of spirituality to their estates were content to deploy statues of St Francis or, for a touch of the exotic, Buddhas or Japanese jizos, or, to raise a smile, the garden gnome.

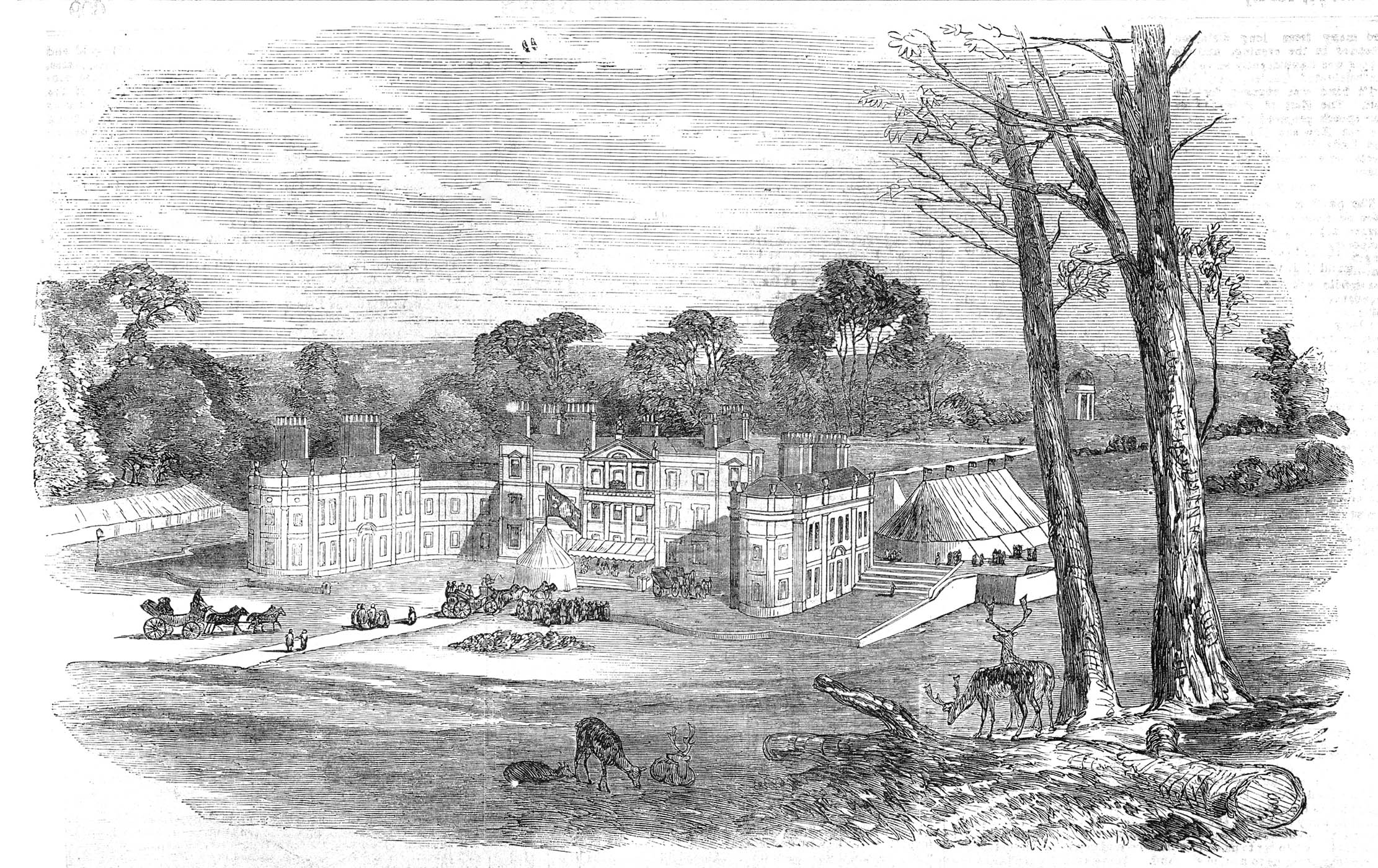

Painshill Park, Surrey: A garden of the Golden Age

This year marks a decisive moment in the heroic restoration of a celebrated landscape garden. Clive Aslet reports.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.