‘My God! What’s he done?… look at it!’: How George Harrison left The Beatles, turned his hand to gardening, and created a masterpiece

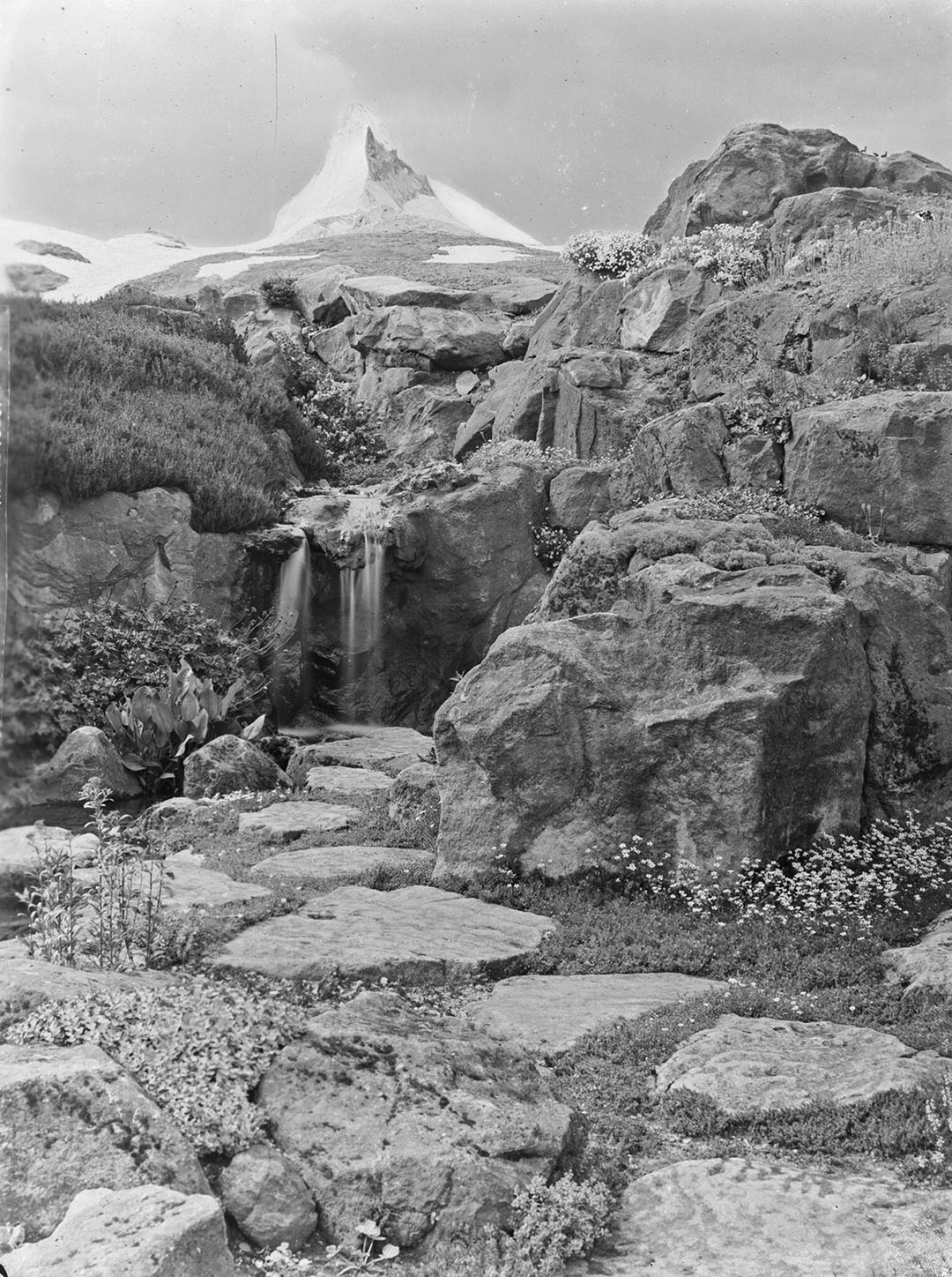

The garden at Friar Park in Henley-on-Thames — the Oxfordshire home of the late Beatle George Harrison and his wife Olivia — is breathtaking. The ‘Gardening Beatle’ did a spectacular job of reviving an historic alpine garden in the shadow of the ‘Henley Matterhorn’, and Olivia has enhanced what was Britain’s largest rock garden with her exceptional and imaginative planting schemes. Charles Quest-Ritson reports.

When George Harrison bought Friar Park in January 1970, there was grass growing up through the floorboards. ‘My God! What’s he done?… look at it!’ his sister-in-law Irene exclaimed. As for the garden, she later observed that ‘you didn’t go for a walk without a machete in your hand to cut your way through’.

Few properties can have had so many advantages and disadvantages as this house on a hill above Henley-on-Thames in Oxfordshire. On the plus side, the former Beatle had found an estate of 30 acres, close to the town, but completely protected from it. It was a place of privacy where he could concentrate on his career as a solo musician — the first thing he did was to build himself a recording studio.

On the minus side was a crazy Gothic monster of a house, surrounded by a jungle of tree seedlings and brambles and an abandoned walled garden thick with glass from all the collapsed greenhouses. The house — which captivated and amused Harrison — would require years to repair. The garden needed complete re-making.

Harrison was 27 years old. His friend Derek Taylor remarked of Friar Park: ‘It is a dream on a hill and it came, not by chance, to the right man at the right time.’ Harrison had enjoyed gardening as a boy — planting and picking his own flowers — and, as an adult, plants appealed to his spiritual sensibilities.

He was particularly interested in trees and shrubs, visiting the Hillier Arboretum in Hampshire and the gardens of Cornwall. When a local nurseryman, Konrad Engbers, remarked that business ‘was a little slow’, soft-hearted Harrison bought one plant of every one of his trees and shrubs. Some years later, in the 1980s, an expert on maples offered him 800 plants, almost all different, and he had no hesitation in buying them. Forty years on, all those purchases make a major contribution to the gorgeous landscapes at Friar Park today.

Although by nature more interested in the present than the future, ‘the Gardening Beatle’ once reflected on life ahead: ‘I can try being a pop star forever and do concerts and be a celebrity. Or I could be a gardener… everyone should have themselves regularly overwhelmed by Nature.’ Gardening offered relief from life’s stresses and he worked long hours in the garden himself. When his son Dhani was young, he knew that what his father did was work in the garden; only later did he discover that Harrison was one of ‘the Fab Four’.

The Victoria County History describes Friar Park as ‘a colourful and eccentric melange of French Flamboyant Gothic in brick, stone and terracotta, incorporating towers, pinnacles and large traceried windows’. It was enlarged and embellished by Sir Frank Crisp, a brilliant lawyer, who bubbled over with charm and energy, but was also an enthusiastic botanist and treasurer of the Linnaean Society of London. He was rich enough, too, to employ 45 gardeners at Friar Park. Alpine plants were his greatest passion and, in 1896, he began to develop his spectacular four-acre Alpine Garden, topped by a scaled-down copy of the Matterhorn.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Crisp’s artificial mountain was by far the largest rock garden in Britain, begun with 23,000 tons of rock from James Backhouse & Son of York, then at the height of their fame and prosperity — their nursery included 40 greenhouses and their own much-visited rock garden. Crisp’s Alpine Garden was constantly extended and improved; James Pulham and Son were brought in to re-landscape it twice. The climb is a gentle wander through small flower-covered outcrops until the rocky hillside leads to an alpine valley and up to a rocky pass with streams, pools and waterfalls along the way. All is dominated by a distant view of the Matterhorn, although the false perspective has now been altered by the growth of the surrounding trees.

Henry Ernest Milner, the leading landscape architect of the day, was commissioned to build an ice grotto underneath ‘the Henley Matterhorn’, variously said to have been modelled on the ice-caves of Grindelwald in Switzerland or the Glacier du Géant below Mont Blanc in France. Stalactites, icicles and an underground waterfall add to the illusion. Halfway up the rock garden, Milner built a large grotto with tufa rocks and innumerable passages and caves, populated by gnomes. Distorting mirrors transform visitors so that they, too, resemble gnomes. When Harrison rediscovered this grotto, some 10 years after buying Friar Park, he had to be carefully lifted down in a hoist to explore it.

Crisp tapped into the flood of new plants that professional collectors brought back from all over the world. The many different habitats within his Alpine Garden were adapted and developed until it contained some 4,000 varieties. Henry Correvon, the distinguished Swiss scholar of alpine plants who wrote for Country Life, was so affected by its ‘unparalleled extent and grandeur’ that he felt ‘suddenly transported in spirit to my native Alps’. He praised the attention to detail in both the design and the plantings and enthusiastically admired the ‘massed groups and broad belts’ that grew and spread ‘as in nature’. He extolled the contrast between rock roses growing on sunny stony slopes, with the ferns and Arctic plants flourishing in north-facing mini-habitats, and he admired many outstanding plants — including soldanellas, daphnes, gentians, Ramonda [formerly Jankaea] heldreichii and lady slipper orchids from three continents.

Crisp’s rock garden and its grottos also housed a multitude of garden gnomes, some as much as 3ft high, and each of them a distinct and different individual, carefully painted in many colours. His sense of humour pervades all the details of the house and garden. Stepping stones across one of the lakes are placed just below the surface, to give the impression of walking on water. When birds went fishing in that lake, Crisp put up a notice that read: ‘Herons will be Prosecuted.’

He was proud of his garden and opened it to the public for many years — sometimes, visiting ladies asked for permission to pick the flowers of Edelweiss. At one time, it was said to be the most visited garden in Britain, but, when he died in 1919, his widow lost no time in selling up.

The property was bought by Sir Percival David, a distinguished sinologist who maintained the gardens very well, but who, after a messy divorce, sold the estate in 1953 to the Salesian Sisters of St John Bosco. The nuns ran a school in the town, but were chronically short of funds. By the late 1960s, both house and garden had run to ruin. The Sisters were refused permission to demolish the house and build houses and flats all over the grounds, before Harrison’s purchase secured their finances and a healthy future for the whole estate.

The Harrisons never thought of restoring the garden to its former design and plantings, preferring instead to acquire plants and place them where they thought best, just as Crisp had done and, indeed, as all good garden-owners do. Harrison put two goats on the rock garden to clear the mass of scrub that had covered it. Some of the overgrowth dated back to 1940, when most of David’s gardeners were called up to serve their country. Nevertheless, the structure of the rock garden was intact, unchanged since the 1890s, which says much for the craftmanship of the original builders. Its resurrection is largely due to the energy and passion of Harrison’s widow, Olivia.

Could the rock garden ever be restored to its full glory of 100 years ago? Probably not. There is a list of plants dating from about 1910, but it covers the whole garden and there is nothing to indicate where anything was actually planted. Mrs Harrison has amassed an interesting collection of old black-and-white pictures, some of them touched up with colouring, but the detail is not good enough to identify the plants with any degree of certainty. One can see, for example, that there were saxifrages, geraniums and campanulas, but have no idea as to their exact names.

Goats are not known to be fussy feeders, so any original plants that had survived the years of neglect were lost, with one exception — the charming creeping Asarina procumbens, usually so difficult to grow, which seeds itself throughout the rock garden. Mrs Harrison thus had four acres of empty mountain slopes with which to start her restoration. Nevertheless, it is remarkable how many of her plantings can be confirmed by Country Life's archive photographs (for articles published on August 4, 1905, May 3, 1913, and August 9, 1919) and have been set exactly where they were more than a century ago.

The lofty Henley Matterhorn is faithfully repainted twice a year, once to show the snow of winter and then in its summer colours. Mrs Harrison has been successful in recovering many of the gnomes and animal ceramics that had been sold off by the poverty-stricken nuns.

Yet when you stand beneath Matterhorn and look down on the complexity and richness of the design and planting, there is no doubt that the restoration of Crisp’s majestic Alpine Garden is an exemplary achievement. It may be only one of Friar Park’s many impressive features — and it is true that all gardening is merely work in progress — but we can be thankful that such an important historic garden is getting better and better all the time.

Getting better all the time: Olivia Harrison's latest Friar Park planting

Olivia Harrison has made some exceptional plantings, including large groups of orchids and Primula vialii, the conical, scarlet tips of which would make elegant hats for dwarves. Sun-lovers include plantings of Paeonia tenuifolia from the Caucasus, Cistus creticus from the Eastern Mediterranean and Eucomis species from South Africa. The size of these plantings recalls the massed groups and broad belts that Henry Correvon admired for their natural effect more than 100 years ago. Shade dwellers have fared equally well, including Veratrum nigrum and Gentiana asclepiadea from the Alps and Kirengeshoma palmata from Japan. Campanulas, dianthus, aquilegias and Erigeron karvinskianus have seeded around and bind the plantings together.

The years of neglect brought two benefits. First, some of the tree seedlings that arrived with the birds have managed to place themselves in cracks in the original stones and boulders. Stunted pine trees grow among the rocks exactly as they do in the Alps. Second, the shelter trees that Sir Frank Crisp planted around the edge of the rock garden have grown to a great height and created sheltered, shady, humus-rich areas for new plantings — some of them astonishingly beautiful.

Mrs Harrison has taken superb advantage of the soil and the dappled shade to establish a valley of tree ferns, a sweep of Podophyllum ‘Spotty Dotty’ and expansive beds for blue Meconopsis betonicifolia and the giant lily Cardiocrinum giganteum. These luxuriant plantings, surrounded by huge boulders, are perhaps the most impressive part of the whole rock garden today.

George Harrison's Garden: How the Beatle and his wife turned a 'tangled jungle' into a magnificent garden

When George Harrison first saw the famous Topiary Garden at Friar Park in Oxfordshire, it was a tangled jungle of

Curious Questions: How did garden gnomes take over the world — and even The Queen's private garden?

Vertically challenged, bearded and rosy-cheeked, cheerful gnomes might make for unlikely cover stars, but — says Ben Lerwill — they’ve

Credit: Kenwood - John Lennon's house in St George's Hill, Weybridge - Knight Frank

Inside the mansion where John Lennon lived at the height of Beatles fame

John Lennon and his then-wife Cynthia bought this beautiful house in St George's Hill as The Beatles were at the

Charles Quest-Ritson is a historian and writer about plants and gardens. His books include The English Garden: A Social History; Gardens of Europe; and Ninfa: The Most Romantic Garden in the World. He is a great enthusiast for roses — he wrote the RHS Encyclopedia of Roses jointly with his wife Brigid and spent five years writing his definitive Climbing Roses of the World (descriptions of 1,6oo varieties!). Food is another passion: he was the first Englishman to qualify as an olive oil taster in accordance with EU norms. He has lectured in five languages and in all six continents except Antarctica, where he missed his chance when his son-on-law was Governor of the Falkland Islands.

-

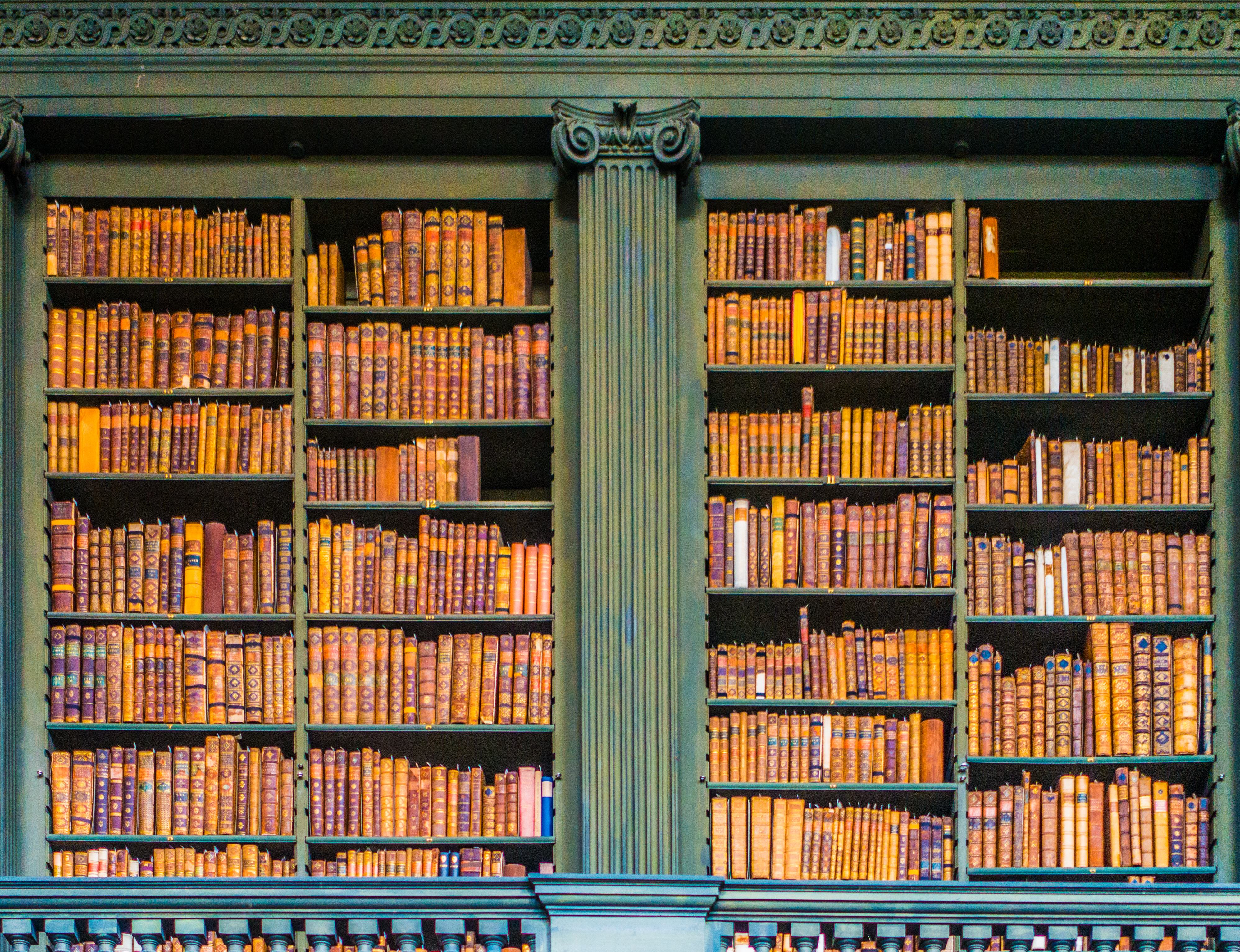

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life