Folly Farm gardens, Berkshire: A masterclass in maintaining an historic garden

After decades of thoughtful restoration, the gardens at Folly Farm in Sulhamstead, Berkshire, blend historic and contemporary planting, finds Tiffany Daneff. Pictures by Jason Ingram.

‘Today,’ Lanning Roper, wrote in Country Life, May 15, 1975, after visiting Folly Farm near Sulhamstead, in Berkshire, ‘such a garden is beyond the realms of possibility in this country.’ He cited the expense not only of upkeep, but of repairs and ongoing maintenance: the photographs accompanying his article show badly cracked paving stones around Sir Edwin Lutyens’s canal.

Fast forward to 2022 and not only have all the flagstones been repaired, but the historic Arts-and-Crafts house and garden, designed by Lutyens in 1906, refreshed in 1912, and planted by Gertrude Jekyll, are in the best of good health. Indeed, they are glowing, thanks to decades of careful restoration, thoughtful replanting and inspired expansion with the help of designer Dan Pearson. The day-to-day care of the gardens is ensured by an expert team headed up by Tim Stretton and overseen by estate manager Simon Goodenough.

Originally, one entered through a gate in the wall directly into one of three small formal courtyards, laid out geometrically in 1906 with flagstone and herringbone-brick paths to balance the rural setting. Now, the approach is via the drive and the forecourt into Barn Court, a private area outside the half-timbered Tudor building that was the original house. Planting here is cool and mainly green, with beds of herbaceous perennials laid out by Mr Pearson in 2010 and since added to with cottage-garden favourites, such as nigella, salvia, euphorbia and thalictrum. The Italian oil jar that once stood on a pedestal has been replaced by the present owners with a terra-cotta beer pot from South Africa, before the thatched barn that gives this garden its name.

Through the arch in the brick wall is the original entrance court, backed by dark yew hedges, and planted with dark colours by Mr Pearson to reflect Lutyens’s designs for the entrance hall in the 1906 house, painted ‘a dull black’, with an arched ceiling, red balconies and a lacquered green floor. There are deep-maroon sweet William, martagon lilies, dark-leafed elder, dark dicentra and terracotta-hued hemerocallis with white-starred gillenia, plus glossy sarcococca for structure. In an indication of the extraordinary attention to detail paid by Lutyens, the brick walls with their corbelled tile overhang are scalloped at the ends near the house, to allow more light to reach the beds below.

So far, so formal as one passes through another arch, where the garden proper opens out to offer the first of many tantalising views, in this case of the Canal Garden. Its dark, slate-lined depths draw the eye south, defying the temptation to follow the path to the right to another area glimpsed through a gap in the yew.

But both must wait. Better to continue straight ahead, along the Tree Peony Borders as steps rise through the Holm Oak Walk. The trees here had to be cut down, having reached an overpowering 70ft, and are in their fourth season of thickening up into a hedge that will provide a backdrop to the lower yew hedge. In early summer, the beds on the left are filled with the lovely heart-shaped leaves of epimediums, paired with strappy green waves of the Japanese forest grass, hakonechloa, on the right, with tubs of lime-white Hydrangea arborescens ‘Annabelle’ lining the path. (In spring, the tubs are filled with yellow Rhododendron luteum.) From this vantage point, one can see how all the yew hedges are cut to the same level, as they were in Lutyens’s time, to hide the natural slope of the land.

Timeline of Folly Farm

- 1650s: A timber-frame cottage is built, gradually enlarged and extended into a farm that now forms part of the north-east wing

- 1906: The new owner of Folly Farm commissions Sir Edwin Lutyens to design the Dutch façade in his popular William-and-Mary style. Gertrude Jekyll creates the two courtyard gardens between the house and the barn

- 1912: Lutyens extends the house for its new owner. This time, it assumes the forms of vernacular buildings—such as farmhouses—to picturesque effect. The Sunken Rose Garden, Dutch Garden, a parterre and new walks complete the garden

- 1920s–40s: The garden is looked after by eight gardeners and the house, described in Country Life (January 28, 1922) as ‘a novel in bricks and mortar’ was used as a maternity hospital during the Second World War

- 1951: The Hon Mr and Mrs Hugh Waldorf Astor move to Folly Farm

- 2007: Folly Farm is acquired by the present owner

Again, we must wait to explore these large and important garden rooms, laid out by Lutyens in 1912, for, winking in the shade ahead, drawing the eye through the impressive avenue of limes, rises a single spout of water. Tucked away, a hidden secret at the end of the avenue, is the White Garden, so called by the Astors, who planted it with white azalea Rhododendron ‘Palestrina’ and Rosa ‘Iceberg’ against a backdrop of white lilacs and philadelphus. Today, the raised stone beds are brimming with, among others, white campanula and Geranium sanguineum ‘Album’ in a multi-layered planting, arranged so that no one species overwhelms another. The walls of these troughs are home to mile-a-minute and ivy, with species allowed to self-seed with just the right amount of laxity.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

In the 1950s, the small rectangular pool at the centre had been drained. In its place stood a stone statue surrounded by hostas, but it is now a pool again, lined with slate, as Jekyll always preferred. Semi-circular at the far end and stepped, it is surrounded by white wisteria and backed by hornbeam trees, topped to allow the light through. When the builders were re-laying the paths around the pool, they were not allowed to use spirit levels so that the paths would look — as, indeed, they do — as if they had been there forever.

A calm green moment arrives, not unlike a refreshing sorbet in a long meal, as one walks through the rectangular lawn of Badminton Court back towards the Dutch Canal. The pair of quince trees at the head of the canal were planted by Jekyll and have been underplanted with sarcococca by Mr Pearson. Recently, one had grown taller than the other, so they are now being levelled. Standing between them, one can appreciate the breathtaking precision with which Lutyens lined things up, so that the water would exactly reflect the roof and front elevation of the 1906 house with its William and Mary-style façade.

These days, the pool is regularly cleaned by robot, because the water run-off from the surrounding fields is high in nitrogen. According to Roper in 1975, Jekyll had originally planted ‘luxuriant borders on both sides of the canal beyond the vases, but these have been eliminated’ and have not been reinstated, which seems wise as the canal benefits from simplicity. Jekyll had wanted waterlilies in the canal, but, Mr Goodenough relates, Lutyens refused, ‘as he wanted his architecture to be seen and, on this occasion, unusually, he won’.

At the curved head of the canal, the white wisteria had been in danger of breaking the delicate balustrade where the water falls in, so it is being trained to hang down the brick piers.

To cover all at Folly Farm in the scope of one article is quite impossible, but, before being drawn towards the billowing perennials in the Flower Parterre, it is worth mentioning the Tank Cloister. This is formed by the magisterial roof of the 1912 house that sweeps down to first-floor level, where it is supported by vast curving buttresses forming an L-shaped cloister around a large tank. This is one of very few Lutyens gardens where water comes up to the house. Building it after his return from New Delhi in India, he gave the tank ziggurat steps reminiscent of those in the Ganges and the gutters that collect rainwater from the two converging roofs have two spouts arranged at right angles, so that, when it rains, the two concentric ripples meet exactly at the centre of the tank. To witness this effect, ‘it needs to be raining heavily,’ says Mr Goodenough, ‘but not too heavily’.

At last, to the Flower Parterre. Nothing remains of Jekyll’s planting (other than her plans), as the beds were grassed over in the 1950s to save work. Thankfully, Lutyens’s stone bird bath that marks the centre of the two axial paths still stands. This huge square of Purbeck marble is hollowed out and filled with an octagonal dish, modelled by the architect on a moghul’s dias. When Mr Pearson reimagined this garden, he looked to Jekyll’s original design, as well as to photographs from the Country Life archive, but, rather than simply copying the planting, he has taken inspiration from it. Whereas she had arranged basins through the beds, planted around with Iris stylosa and pampas grass, Mr Pearson took the dimensions of the stone bath and replaced the basins with box cubes, which provide just the right structural reassurance for the lovely loose planting, as well as echoing the square-based geometry of the garden.

Miscanthus grasses form a major part of the plant architecture and, as the seasons progress, there are successional waves of bold planting groups that are designed to be viewed from the living room. They include swathes of astrantia, long-lasting purple-blue spires of Salvia nemorosa ‘Caradonna’ and similarly hued Salvia verticillata ‘Smouldering Torches’, interspersed with sinuous spikes of white Eremurus himalaicus.

If, as Christopher Hussey opined (Country Life, January 28, 1922), ‘the gardens of Folly Farm exercise much wider attraction over people than the house’, then it is fair to say that no part of the garden does this more than the Sunken Pool Garden. This is arrived at through a gap in the yew hedge that separates it from the Parterre and who does not stop, at the boundary, and marvel? Laid out in 1912 by Lutyens, this area was based on the design of the ancient Indian board game Pachisi. Similar to Ludo, its square board has four ‘homes’ or, in this case, four raised platforms reached by curved steps, where mounds of Euphorbia mellifera ‘Roundways Titan’ reach more than 9ft alongside benches that catch the sun at different times of day. Around the edges run herringbone-brick paths and at its centre is an octagonal pool enclosing an island. The central island was filled with lavender in Jekyll’s day and, by 1922, the garden had been devoted to roses with flowering cherries. Roper noted that the lavender had been replaced by Brachyglottis greyi in 1975.

Indeed, he found the architectural design ‘perhaps over-complicated’ and it may have been for the roses, which eventually succumbed to mildew and blackspot in this enclosed space where circulation is poor. Such conditions are, however, ideal for the exotic planting introduced by Mr Pearson. This looks resplendent and allows Lutyens’s design to shine. Some of the original Eryngium agavifolium are now being thinned and a few annuals, such as the red Geum chiloense and orange-flowered G. coccineum ‘Cooky’, are being introduced to add to the bright spots of colour provided by Crocosmia ‘Columbus’, C. ‘Emily McKenzie’ and C. ‘Red King’, as well as Kniphofia ‘Green Jade’, K. ‘Rich Echoes’, K. rufa and K. ‘Timothy’. In addition, large pots, planted by Ann Williams, the gardener in charge of ornamentals, provide a stand-out selection of mixed species that includes, in one example, Ipomoea ‘Sweet Caroline Sweetheart Jet Black’, Petunia x Petchoa ‘Beautiful Caramel Gold’ and martagon lilies, as well as a mix of succulents.

There are further treats in the Wind Garden, where Mr Pearson, continuing Lutyens’s play on squares, transformed the old croquet pitch into a grid of four by five square platts planted with a repeating, but slightly different, combination of grasses, shrubs and camassias that sway in the breeze. In autumn, the square of cornus underplanted with black ophiopogon turns a dramatic red and black.

Beyond stretches the more recent addition of a wildflower meadow and a pond, with small plank bridges leading to the Walled Garden, which measures exactly one square acre. This is divided into four equal quarters, with a dipping pond in the middle and cruciform paths, and is maintained to an extraordinarily high level, its many species ingeniously displayed. At the entrance, Lavender grosso is planted, Grasse style, in long rows (and replaced on a five-year cycle), interspersed with rows of agapanthus, catanche and Centaurea orientalis. To the left, Rachel Roncon, who leads the Walled Garden team, is responsible for an impressive display table arranged on staging, with terracotta pots filled, in summer, with diascia, pinks, nicotiana, London pride and astrantia, among others. Every fortnight, the selection changes.

There are masses of flowers for cutting, a collection of clematis, soft fruits, asparagus, roses and a citrus collection. In one corner, reached via a stepping-stone path through a lawn of camomile, is the Flower Drying Room. Around the vine pergola, where the family eats in summer, are arranged pots of begonias, sage and cerinthe and yet others brimming with the healthiest-looking blueberries. As for the raised beds… words fail. Violas are planted with beetroot in one, hop poles rise above subtropical summer bedding in another and hazel wigwams twined with gourds are set among sunflowers and squash.

This is a garden that lingers powerfully in the memory and is one that I hope will continue to be cherished in the decades to come, as it is so well cherished now.

-

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'The Paper Mill estate is a picture-postcard in the Garden of England.

By Penny Churchill

-

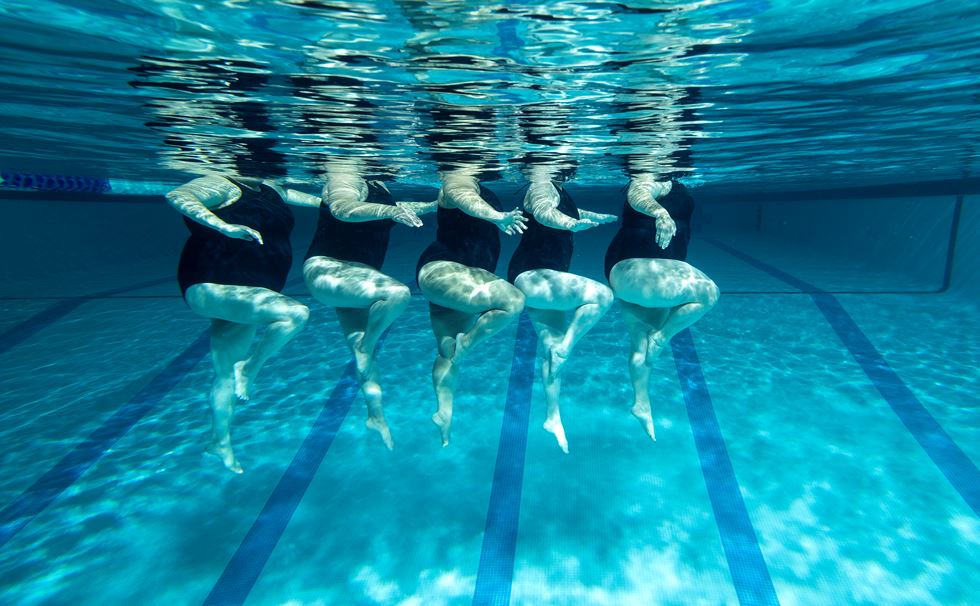

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead Heath

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead HeathEmma Hughes dives into swimming's hidden depths at the Design Museum's exhibit in London.

By Emma Hughes