Ablington Manor: A magnificent house and gardens almost untouched by the passing of time

Ablington Manor: A magnificent house and gardens almost untouched by the passing of time

Ablington Manor in Gloucestershire is one of those ancient, hidden-away places that, after the dissolution of the monasteries, gained status in the time of the Tudors as the seat of a prosperous trader.

One John Coxwell, who had made his money in the burgeoning wool trade, built the present house in about 1590. It underwent various alterations in succeeding centuries, but the appealing, multi-gabled house still sits in a place of great natural beauty, seemingly little altered by the passing of time.

More than a century ago, a former tenant of the manor, J. Arthur Gibbs, published A Cotswold Village (1898), noting down his first observations of the property and its garden: ‘A broad terrace running along the whole length of the house, and beyond that a few flower beds with the old sundial in their midst.’

Save for a cornucopia of ancient hump-backed yews, the rest of the landscape was (and is) dominated by the estate’s natural contours, for Gibbs continues: ‘Beyond these a lawn and then grass sweeping down to the edge of the river (Coln)… and beyond more grass but of a wilder description, and in the background a magnificent hanging wood, crowning the side of the valley.’ In winter and spring, this is the most commanding and alluring of views.

Robert Cooper, the present owner, bought the manor in 1975 and recalls its descript-ion of ‘a village manor house with a pretty adequate garden’. He was joined by his wife, Prudence, some 20 years ago and, together, they have developed the garden with imagination and careful planting and were long aided by Leslie Blackwell, head gardener for 40 years, who recently passed the baton of responsibility to Jason Rice.

Mr Cooper recalls how he first took on the monumental task of clearing and restoring the then derelict and abandoned ‘hanging’ woodland, an impossibly steep, tree-clad bank which concluded the vista from the house. Fallen and damaged trees were cleared or felled in order to create a naturalised daffodil cascade.

Between the newly thinned, largely deciduous beech woodland, he planted 17,000 Liberty Bells narcissi: ‘I thumbed through bulb catalogues and liked the look of its long trumpet and reflexed perianth.’ He enjoyed their buttery twin-headed blooms for a decade before their natural demise: ‘I replaced them with Avalanche, drawn by their name rather than suitability for the cascade – we had one splendid year, then nothing.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Now wiser, he says, Mr Cooper has replenished the woodland with a succession of mixed, long-lasting heritage Narcissi stocks, including March-flowering Tom Thumb and scented Actaea, flowering from April into May.

The steep contours of the hillside end abruptly, flattening into a broad, grassy riverside glade. To the west, the Old Island had silted up at some stage; conjoined to the south bank, it lay derelict, barricaded off and strewn with rotting wooden duck houses. The Coopers took down the palisade fence, cleared away the debris, nettles and bindweed and incorporated the newly moss-cushioned glade into the garden.

They planted masses of spring wildflowers and bulbs: winter aconites and snowdrops are followed by pale-lemon primroses and cowslips, glacial-blue Puschkinia scilloides and blue-starred Chionodoxa, among which a deer sculpture by Hamish Mackie looks up, towards the house.

The south bank’s naturalistic idyll is discreetly interwoven with a more formal tracery. A mid-19th-century stone bridge over the river leads directly to a 200-year-old croquet lawn, bordered with springtime clusters of dark-red hellebores, notably Anna’s Red, followed by peonies and then clouds of late-summer macrophylla and paniculata hydrangeas.

A lengthy wooden pergola, weathered silver, is thick with promising rose and honeysuckle stems; it divides the lawn from a three-year-old wildflower walk in which 3,000 Fritillaria meleagris have been planted, to be succeeded by ribbons of ox-eye daisies, chamomile, cornflowers, corn cockles and poppies. A nearby pet cemetery commemorates various dogs and Polly, a favourite hunting mare.

Beyond a Cotswold-stone pavilion, a second pergola, built in 1997, commemorates Mr Cooper’s mother and is embowered with Paul’s Himalayan Musk roses, which must be an exceptional sight when flowering occurs through June. It culminates at a second river-crossing point, a simple wooden footbridge, added in 1985 during the weir’s restoration, facilitating a circular tour of the garden.

The riverbanks have been fortified to prevent further silting and erosion and they have formalised another island in the river. Here, although a more formal garden structure presides, the thread of informal spring plantings allows a seamless transition from countryside to garden.

Mr Cooper overlaid what had been a ‘shifting gravel terrace’ of the house terrace with thick slabs of York stone, salvaged from Leeds Old Town Hall in 1985. Their narrow, geometric clefts are softened with a gauze of pale-blue Muscari Valerie Finnis, and indigo M. Dark Eyes. In summer, blush rock roses, Helianthemum Wisley Pink, push through the cracks. Complementary stone troughs and urns, planted with diminutive, pale Narcissus W. P. Milner and ice-blue Iris reticulata Katharine Hodgkin, fringe rather than conceal the commanding lawn to river views.

According to Gibbs’s A Cotswold Village, he ‘had never seen grass so green and fresh looking, except in certain parts of Ireland’. This holds true today and the Coopers attribute the lawn’s lush greenery to regular scarification, which ‘removes moss and thatch allowing the lawn to breathe’.

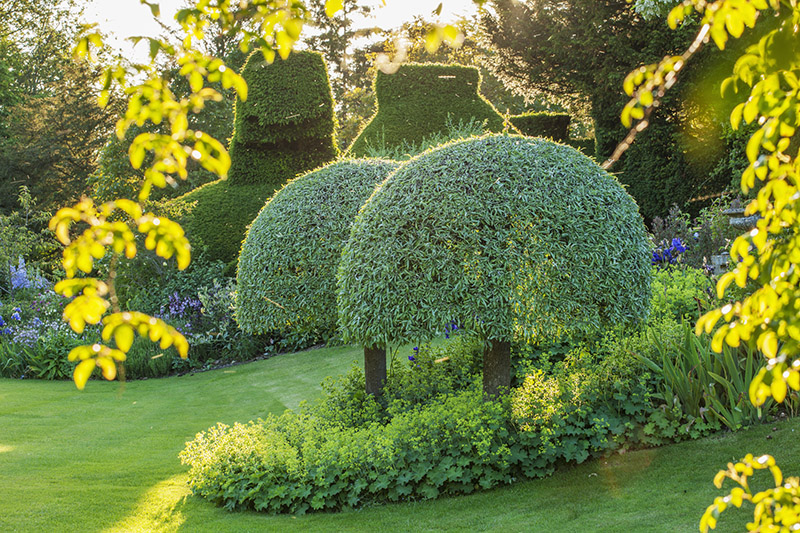

A thick, tulip ribbon of creamy T. World Friendship separates the lawn border from a monumental, 300-year-old gigantic yew and box ‘sculpture,’ described by the Coopers with tongue in cheek, as ‘the last work of Henry Moore’. Clipped by hand by Leslie Blackwell for many years, there’s rhythm if not reason to this comely edifice.

This ‘Modernist sculpture’ is counterbalanced by more the conventional clipped topiary of the lawned mid terrace. Flanking the York-stone steps is a quadrant of tightly clipped Pyracantha balls, tucked between four dumpling golden yews (planted in about 1900), around the old stone sundial. Two weeping pears, Pyrus salicifolia Pendula, have been pruned to mushrooms and potentilla is cut to a low, boxy hedge, which flowers white each summer.

The lawns are embroidered with more swathes of scilla and narcissi and bejewel-led with amethyst early-flowering Crocus tommasinianus followed by bolder Dutch cultivars, the lot only mown once the flowers are spent. To the east of the lawn, carved yew buttresses add structure to a serpentine border, designed, Mr Cooper explains, to acknowledge that ‘Nature doesn’t always work in straight lines’.

Beyond, but hidden, lies a more traditional, sunken walled garden, again sprinkled with spring bulbs and with hellebores Anna’s Red and Penny’s Pink. ‘We cut back hellebore foliage in winter to save the flower buds from hungry mice, which dislike the more open exposure,’ he advises.

Ablington Manor Garden, Ablington, Cirencester, Gloucestershire (01285 740363; prue@ablingtonmanor.com. Visits to the garden are by prior appointment only, March–September, but there is a Royal British Legion open day on Sunday, July 1 (2pm–5pm).

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Country Life 23 April 2025

Country Life 23 April 2025Country Life 23 April 2025 looks at how to make the most of The Season in Britain: where to go, what to eat, who to look out for and much more.

By Toby Keel

-

The big reveal: A first look at Country Life's RHS Chelsea Flower Show stand

The big reveal: A first look at Country Life's RHS Chelsea Flower Show standInterior designer Isabella Worsley reveals her plans for Country Life’s ‘outdoor drawing room’ at this year’s RHS Chelsea Flower Show.

By Country Life