Bringing Mediterranean planting to Britain with the most wonderful gardening book of the year

Mark Griffiths explains why we value Mediterranean planting styles so highly, why he urges all to purchase Mr Filippi's 'Bringing the Mediterranean into your Garden: how to capture the natural beauty of the garrigue' and why he would never adopt the methods described within himself.

Over the past 30 years, Olivier and Clara Filippi have built up Pépinière Filippi (www.jardin-sec.com), a nursery, at Mèze in the Midi, France, that specialises in Mediterranean flora. They have also pioneered an approach to garden-making that’s new for the region. It uses native species in schemes that replicate their wild habitats, deploy no artificial irrigation and give free rein to the dynamics that operate in natural ecosystems.

Last month saw the publication of M. Filippi’s beautifully illustrated volume on this revolution: Bringing the Mediterranean into your Garden: how to capture the natural beauty of the garrigue (Filbert Press, £40). May seems early to be naming one’s gardening book of the year, but there’s no resisting the maquis in these pages.

Much as I admire M. Filippi’s approach, I could never adopt it.

I need to cultivate a wider range of species, as closely as each requires. One wouldn’t deprive domestic animals of water, so why stint garden plants? But I do relish this book for its field notes, plant inventory and design ideas.

In any case, Mediterranean gardening in Britain is not the same as it is in the Mediterranean, as M. Filippi allows. Our climate is still different, as is our attitude to the plants concerned. They’re exotics to be tended and treasured; they’re not even all from the Med.

Our fondness for growing them probably took root during the Roman occupation, but the first documented flowering didn’t happen until the 16th century. The Elizabethan gardening cognoscenti cultivated Tamarix, Phillyrea, olives, holm oaks and cypresses, as well as lavender, rosemary, Cistus, Santolina and Artemisia. Come winter, many survived unprotected, albeit in the embrace of walled gardens.

Then, our climate went north as the Little Ice Age bit hard. By the 1670s, John Evelyn was lamenting the cold’s devastation of Mediterranean prizes. Gardeners lost sight of them until the 19th century, when botanical travellers reacquainted us with this frost-banished flora. Charmed, we resolved to risk these plants outdoors again, only, this time, we learnt to propagate them and to keep a few of each in reserve under glass over winter.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Before long, we were discovering that Mediterranean-like areas occurred around the world and that their plants deployed similar strategies against sun and drought: chiefly, their foliage, which ranged in texture from fleecy to succulent, wax-bloomed, bone-hard and filigree-fine, and in colour from silver to hoary-white, blue-grey and bronze.

These various complexions account for some of our gardens’ most striking and beautiful accessions: Corokia cotoneaster and Olearia macrodonta from New Zealand; Acacia bailey-ana Purpurea and Leucophyta brownii from Australia; Melianthus major and Kniphofia caulescens from South Africa; Fascicularia bicolor and Colletia paradoxa from South America; Romneya coulteri and Yucca rostrata from the American South-West; Elaeagnus Quick-silver and Pyrus salicifolia Pendula from the Caucasus; and Crambe maritima and Eryngium maritimum, our own dear native sea kale and sea holly — both native wildflowers of Britain.

I used all the above in the first of many gravel gardens I’ve made – along the south face of my family home in Buckinghamshire. It was also ‘full of the warm South’, however, upholstered with silver-grey shrubs and perennials from the garrigue, maquis, matorral and phrygana.

Their hardiness worried me more than that of their Southern Hemisphere companions. I’d over-winter spares of my favourite Cistuses, Teucrium fruticans and Phlomis italica in a cold frame and fret about frost on Helleborus lividus and Paeonia cambessedesii, two Balearic beauties that bloomed too early for safety. Often, the worry turned out to be warranted: this was in the early 1980s, when our winters were still long and hard.

Soon afterwards, our climate began growing noticeably milder. Mediterranean planting prospered. As a policy, it saved on water and labour, as two Essex masterpieces, Beth Chatto’s Gravel Garden and Hyde Hall’s Dry Garden, illustrated.

As a style and plant palette, it offered ever more pleasures. We could now grow olives, Italian cypresses and the fan palm Chamaerops humilis, all previously deemed tender. The influx of suitable candidates from beyond the Mediterranean also increased and it continues.

Recently, for example, it has brought us Senecio candidans Angel Wings, a prodigious perennial, with large and luxurious, silver-pelted leaves, that turns out to be far tougher than people imagined – but then what else would one expect from a Falkland Islands native?

So I stand by our version of the Mediterranean garden – eclectic, outlandish, artful and nurtured – at the same time as urging ‘Do buy M. Filippi’s book’.

Mark Griffiths is editor of the New Royal Horticultural Society Dictionary of Gardening.

-

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera season

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera seasonBy Annunciata Elwes

-

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'A party barn is the ultimate good-time utopia, devoid of the toil of a home gym or the practicalities of a home office. Modern efforts are a world away from the draughty, hay-bales-and-a-hi-fi set-up of yesteryear.

By Annabel Dixon

-

Dawn Chorus: How to travel around the world in 19 flowers and the Mini Moke that took St Moritz by storm

Dawn Chorus: How to travel around the world in 19 flowers and the Mini Moke that took St Moritz by stormWhat do Charles Dickens, Henry VIII and Ellen Willmott all have in common? They all appear in a new book chronicling 19 flowers and the people responsible for bringing them to the UK. Find out how to get your hands on it, plus, we reveal why a rare Beach Boys-inspired Mini Moke turned up in a Swiss ski resort and a few of India Knight’s favourite things.

By Rosie Paterson

-

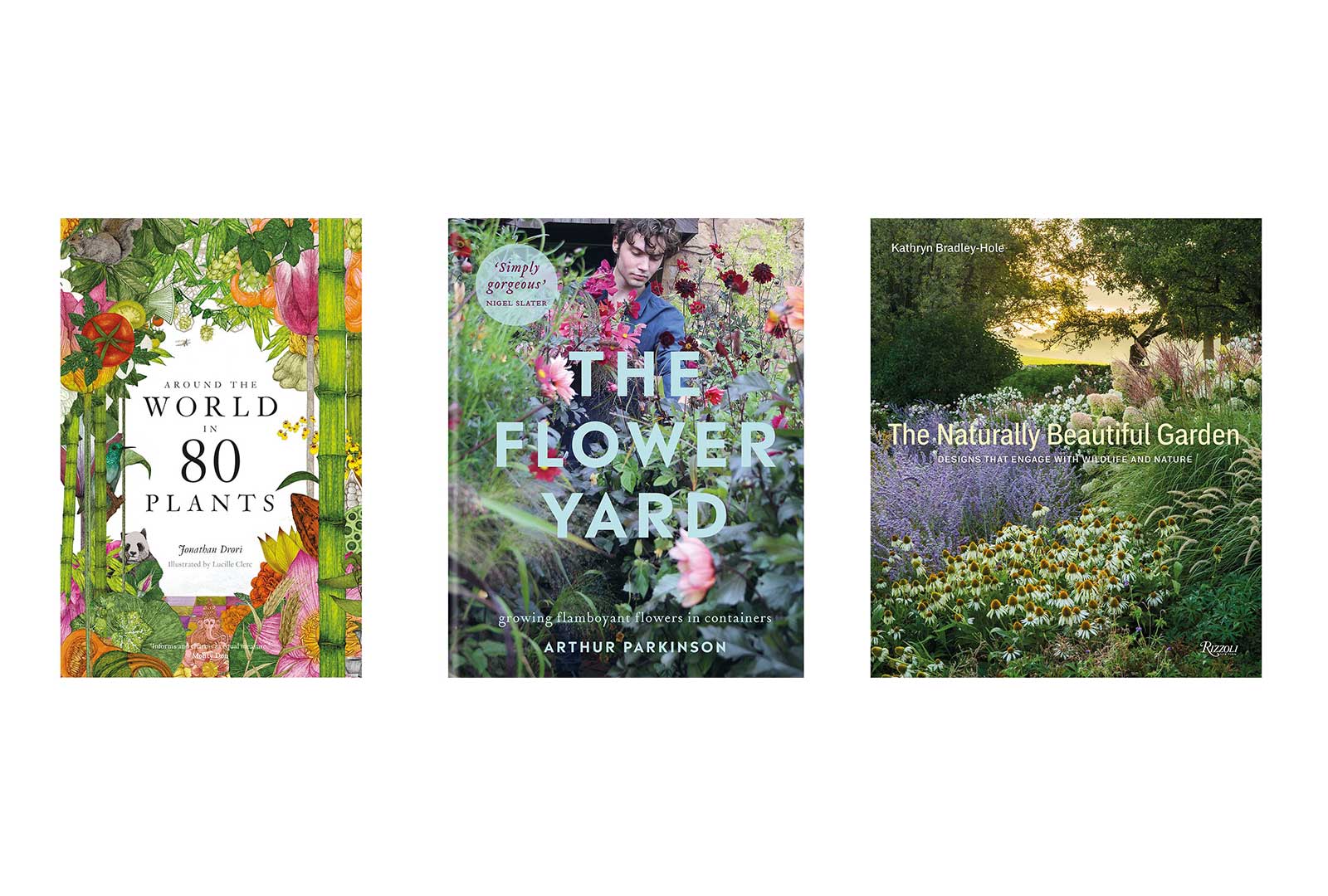

The best gardening books for summer

The best gardening books for summerOur gardens editor Tiffany Daneff picks out her favourite new books on gardening, featuring the likes of Sarah Raven, Arthur Parkinson and her predecessor at Country Life, Kathryn Bradley-Hole.

By Tiffany Daneff

-

Curious Questions: How the Monkey Puzzle tree get its name?

Curious Questions: How the Monkey Puzzle tree get its name?One of the most curious trees you'll see in Britain is also one of the most curiously-named: the Monkey Puzzle tree. But how did it get its name?

By Mark Griffiths

-

The last word on Capability Brown – but one which comes with a health warning

The last word on Capability Brown – but one which comes with a health warningThis book on Lancelot 'Capability' Brown by the greatest living expert on his work is like nothing else – but it comes with one or two caveats, as George Plumptre explains.

By Country Life