Benefits of the changing climate

Doom-mongers who say that climate change will make spring disappear are utterly wrong, says Kathryn: just look at Mediterranean gardens in springtime.

At least there are some benefits to be had from our changing climate. Spring flowers, including wildflowers, have been exceptional this year; lady's smock, bluebells and primroses have bloomed in prodigious quantities, and Anemone nemorosa, the native white wood anemone, made some southern woodlands seem as if the trees were rising out of deep snowdrifts. So the drought and high temperatures that occurred last summer, followed by a good, wet winter, were really perfect conditions for ripening and replenishing. That winter rain is the all-important factor.

The doom-mongers, always gathered under the convenient heading of 'scientists' in the media, tell us that England will become 'Mediterranean' with hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters. They may be right, and we will all be sorry if it leads to the gradual loss of our loveliest woodland trees, but they are wrong when they say that spring, as a season, will 'disappear' as a consequence. On the contrary, if they actually went to Mediterranean lands in spring, as many gardeners habitually do, they would see that it is a breathtaking season: fragrant, balmy and awash with countless beautiful wayside flowers (wild gladioli, irises, cyclamens, narcissi and orchids galore, to name a few), and enough glamorous butterflies to quicken the pulse of any lepidopterist. Summer, of course, is another matter, but let us rejoice in the prospect of spring being ever more beautiful and bountiful.

One tree that will not mind what sort of climate we end up with is the Black Locust, or False Acacia, Robinia pseudoacacia. Although actually a native of North America (British colonists in America discovered it in 1607, at Jamestown, Virginia), it has found a congenial home throughout Europe, the Mediterranean region and southern Africa. It is a tree I am very fond of, for when in full sail, it's a graceful thing, suggestive of those misty trees filling out the middle distance in 18th-century landscape paintings, in all their feathery lightness. Its own successful colonisation is due to its great adaptability, for this is a David Cameron of a tree, coping with a very wide range of habitats, and managing to be all things to all men: airy, decorative and shady, but unshaken when the going gets hot.

Even so, occasionally it gets its comeuppance for being so adaptable. In Scotland, Robinia pseudoacacia is now a forbidden plant, officially classified as 'invasive', and not to be placed anywhere in the countryside. The invasiveness comes from its ability to send out suckers from its roots, enabling saplings to turn up all over the neighbourhood.

There are other reasons why it is not universally popular. Its branches, being rather brittle, need little provocation to break off in a gale. Then there is the maddening way it sheds yard long, viciously spined twigs in every week of the year, a minefield for people and pets. It was the latter problem that finally called time on our own Robinia last week that and the fact that it was, unfortunately, in entirely the wrong place. So, in came the tree surgeons to despatch it, which they did with great speed, and followed this up with a stump grinder, to get the rest of it out of the ground. So often, when mature trees are felled, the trunk is sawn off at ground level and left in situ. But leaving the stump behind is unsightly, its slow rotting can invite diseases such as the dreaded honey fungus to settle, and, of course, it stops anything else being planted in the same spot.

The rotating grinder works in the manner of a dentist's drill (and sounds not unlike one, although much louder). As it chomps away, eating further and further into the depths, it reduces the main root to sawdust, which can be easily swept up and the cavity filled with soil for replanting. Tree surgeons don't always volunteer the option of bringing in a stump grinder they are unwieldy machines and, of course, they increase the price of the job. But it is well worth insisting that as much as possible is removed, and there are grinding machines small enough to wheel into urban gardens, provided the access is available. For all its faults, I shall miss our feathery Robinia; but its passing has opened up a sunny opportunity just right for the alluring flora of the Mediterranean.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

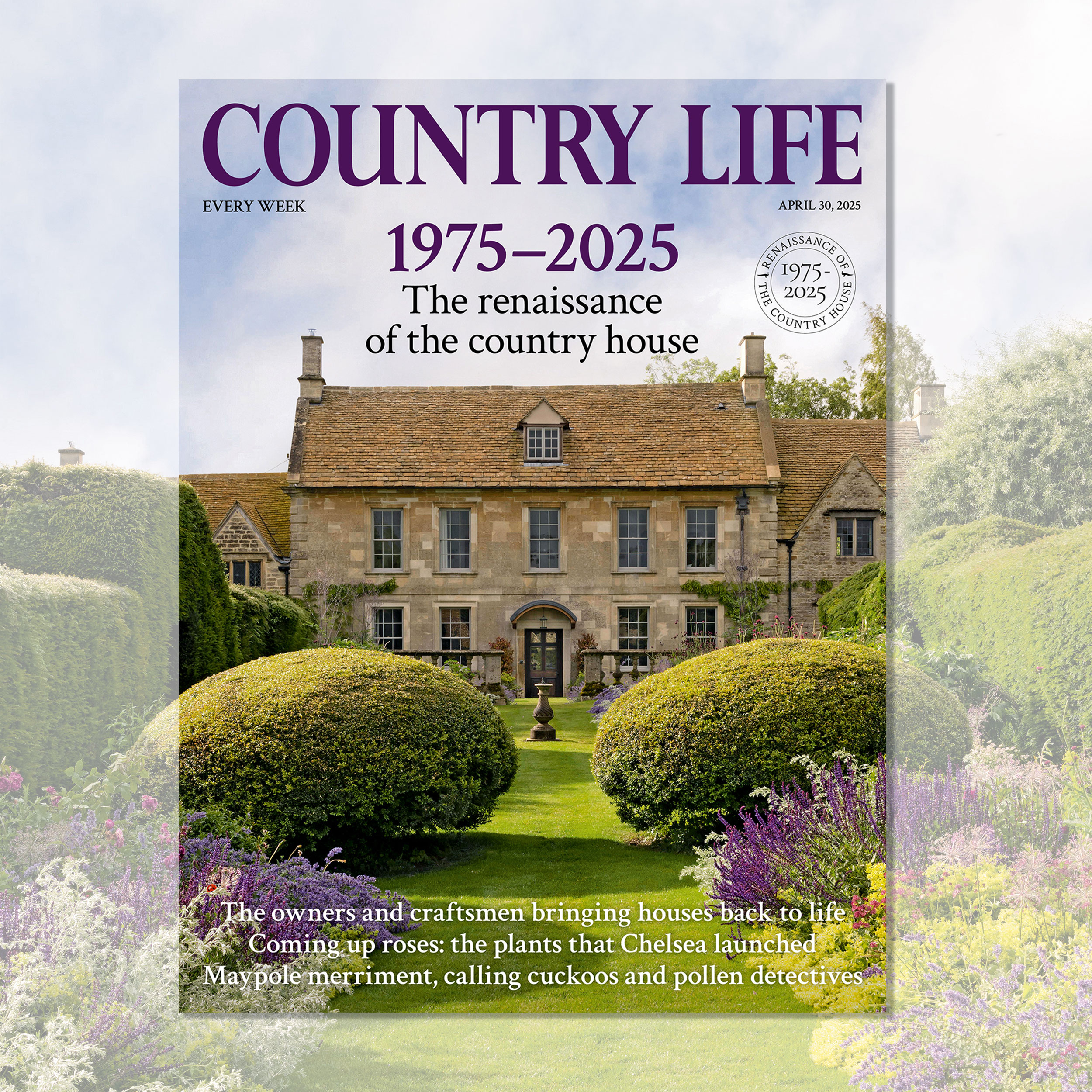

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

George Monbiot: 'Farmers need stability and security... Instead, they're contending with chaos'

George Monbiot: 'Farmers need stability and security... Instead, they're contending with chaos'The writer, journalist and campaigner George Monbiot joins the Country Life podcast.

By Toby Keel

-

Country Life 30 April 2025

Country Life 30 April 2025Country Life 30 April 2025 is a glorious celebration of the country house in Britain, and the tale of its renaissance in the last fifty years.

By Country Life