Alan Titchmarsh: Why I wish I’d planted Cedars of Lebanon when I was in my 20s

The gardener writes about one of his regrets with regard to his favourite type of tree.

Living in a world in which, to most politicians, the phrase ‘long term’ means two parliaments, it’s an uphill struggle to get anyone with an eye to the future to think further than the next 10 years. However, true gardeners do and must.

‘Plant pears for your heirs’ the saying goes and, although the innate pessimism in that statement is questionable (nowadays, most folk under the age of 70 can reasonably expect to enjoy poires Belle Hélène from a tree they’ve just planted), it’s hugely satisfying to plant other trees that will not come to full maturity until long after we are gone.

Although this may be taking the postponement of gratification to its extreme, I can’t help but feel a rising sense of pride in the three cedar of Lebanon trees (Cedrus libani) that I planted in the meadow behind our house some 15 years ago. They were just 6ft tall when I dug the holes and tucked them into the well-drained but chalky earth. Now, they’re 30ft high, with fairly wide-spreading branches – a couple of centuries away from maturity, but lusty enough to gladden my heart and provide shade from the sun.

How I wish I’d been in a position to plant them in my twenties, rather than my fifties, as I could then have really seen them flexing their muscles.

"I see in my mind’s eye my great-grandchildren playing games in the shadow of the stately trees"

From time to time, I’m asked to name a favourite plant or tree for some survey or other. Depending on the time of year, it might be a snowdrop, a daffodil, an iris, a peony or an old-fashioned rose. I have a fondness for old apple trees when they’re laden with their coconut-ice blossom, but, if I’m allowed to choose only one tree on my desert island, it’ll be a tough decision between an English oak (Quercus robur) and the cedar of Lebanon, for both have a grace and majesty that keeps a man in his place and reminds him of his responsibility to the Earth and the relative brevity of his time upon it.

Highclere Castle – the home of the Earls of Carnarvon near Newbury, and now better known for its starring role in Downton Abbey – would lack much of the grandeur it possesses were its appearance solely dependent upon the talents of the architect Sir Charles Barry; it’s the 300year-old cedars that create and enrich its setting.

Cedars need space to achieve best effect. There are three main species: Cedrus atlantica, the Mount Atlas cedar (usually found in its blue-grey form, Glauca), bearing slightly ascending branches; the deodar – Cedrus deodara – fresh green with pendent shoot tips; and C. libani, which is the classic cedar of Georgian parkland, whose branches are almost horizontal.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The deodar is the most attractive in its early decades, but the other two species are arguably the ones to choose should you wish to leave behind a green legacy. Given any decent well-drained soil, all of them will thrive.

Just last year, I removed the very lowest branches on each of my trees. It was a difficult decision – I didn’t want to turn them into Christmas trees – but many of the lower, overshadowed stems were weak or dead; regular removal of any such material is about the only maintenance the trees need, apart from making sure that, in their early years, they have one strong leading shoot that will allow them to extend heavenwards.

Heavy snowfall can inflict severe damage on mature trees. It can’t be guarded against, but with young trees, it’s easy enough to knock off the snow, thus preventing disaster in its youth and disfigurement in old age. ‘God bless the family,’ wrote A. P. Herbert in his frothy musical comedy Bless the Bride. ‘Like our great cedar tree, ascending, swelling, and ever spreading richer roots below.’

I see in my mind’s eye my great-grandchildren playing games in the shadow of the stately trees that were not much taller than me when I planted them. It is, I think, a fine sentiment for any gardener to live by.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Gill Meller's recipe for a seasonal new potato omelette, with smoked garlic, onions and Cheddar cheese

Gill Meller's recipe for a seasonal new potato omelette, with smoked garlic, onions and Cheddar cheeseBy Gill Meller Published

-

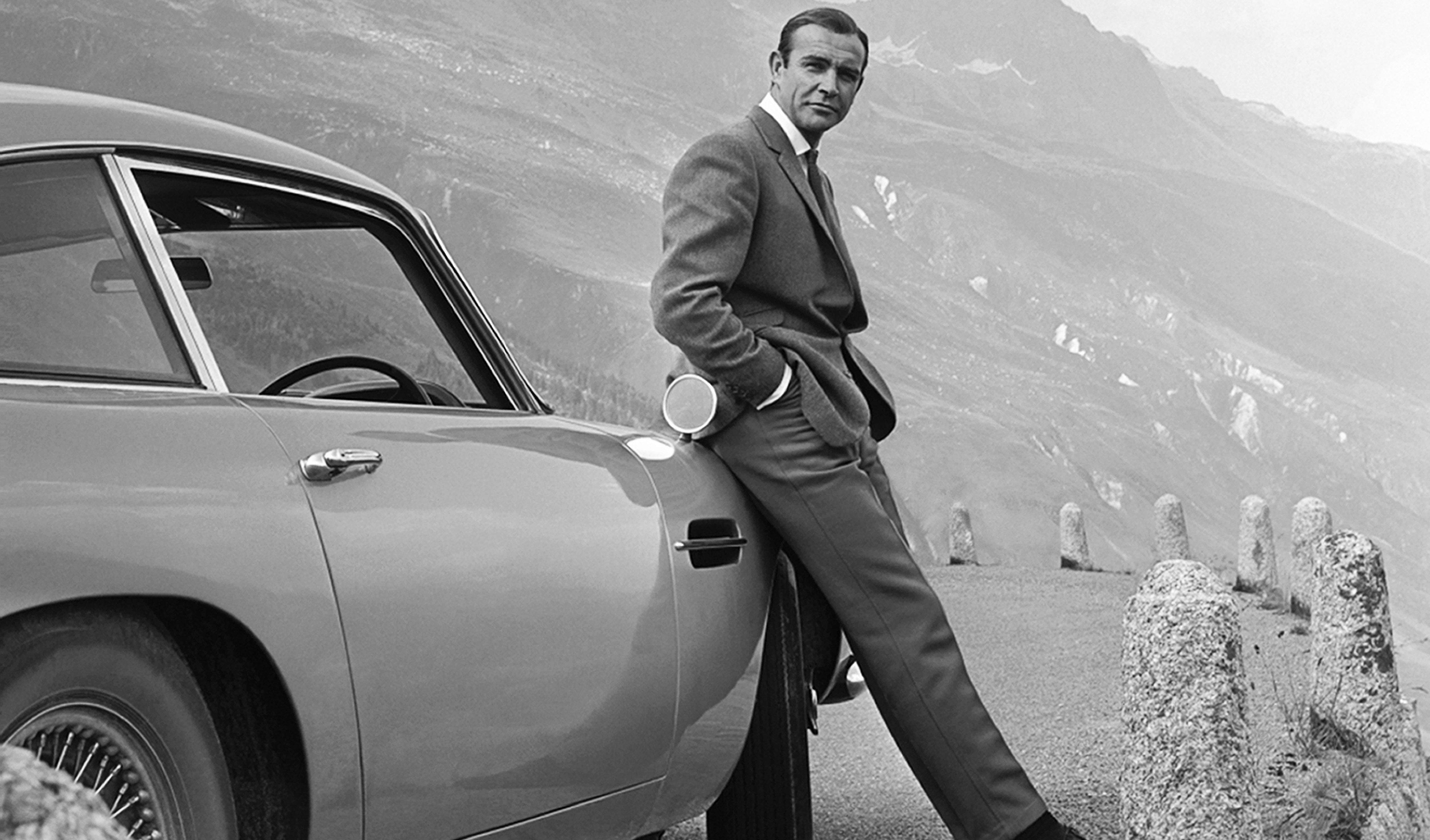

Bond's Aston Martin and Welsh rarebit: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 10, 2025

Bond's Aston Martin and Welsh rarebit: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 10, 2025Thursday's quiz celebrates pedestrian crossings and tests your language skills.

By Toby Keel Published