24 hours in Oxford, from the Botanic Garden to the Bodleian Library

Oxford’s unique mix of history, art, nature and architecture make it the ideal place for a short break. Our gardens editor Tiffany Daneff paid a visit to the famous Botanic Garden — and found she still had time to fit in several more of the city’s great treasures.

402 years ago, Henry Danvers — the First Earl of Danby — decided that he wanted Oxford University to have a physic garden where medical students could be taught about the uses of medicinal plants. The result was Oxford Botanic Garden, a place that’s every bit as fascinating today as it must have been when it first opened in 1621.

On a chilly winter’s morning when beads of condensation weave and drip their way down the clouded panes the glasshouses are decidedly the right place to be. Who knew that such exotics were here, just a few steps from the edge of the River Cherwell which forms the western boundary of the Gardens.

Before any plants could go in the land, sitting on the river’s flood plain, had to be raised. For the next 20 years “four thousand cart loads of mucke and dunge” were brought in and a wall with four gateways was built to enclose the Garden. The first Keeper of the Garden, Jakob Bobart the Elder (c1599-1680), was appointed in 1642 following which planting began.

It became known as the Botanic Garden in the 1830s to reflect its main focus on experimental botany and taxonomy. Since then, the gardens have gained another three acres from Christ Church College, and in 1963 it took on the running of the eight acres of pinetum at the University’s Nuneham Estate, a few miles outside the city at Nuneham Courtenay, which has since expanded to form the 130 acre Harcourt Arboretum.

Today the Botanic Garden and Harcourt Arboretum together cultivate 5000 different plants used in research, teaching and conservation as well as being open to the public.

What to see at Oxford Botanic Garden

The glasshouses

There are some impressive specimens in the Arid House including a dragon fruit, Hylocereus undatus — those odd-looking often bright pink fruits now available in supermarkets with white flesh, black seeds and a somewhat dubious flavour. This is not a fruit you would have suspected had come from a cactus. Dragon fruits are native to South America where their large white flowers (almost a foot across) open at dusk and last one night during which they are pollinated by moths and bats.

You’ll find cocoa plants and bananas in the Rainforest, venus fly traps and pitcher plants in the Carnivorous glasshouse. The catapult pitcher plant in the Cloud Forest catapults insects that land on the underside of the lid of the pitcher direct into the fluid-filled pitcher.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Citrus House, as you might expect, is filled with all kinds of citrus fruits — breathe in their wonderful scent — including the strange yellow-fingered fruits of the Buddha’s hand citrus, Citrus medica.

Tolkein’s tree

On June 8th 2021, to celebrate the garden’s 400th anniversary, His Majesty The King — then the Prince of Wales — planted a black pine, Pinus nigra, which was grown from the seed of the original black pine that had been much loved by J R R Tolkein when he was at Oxford. The new planting was an act of restoration: the original tree had been planted around 1830, but had had to be removed in 2014 after it lost two limbs.

The Cheshire cat

Lewis Carroll and Alice Liddel used to visit the Botanic Gardens and in their memory the sculpture of the Cheshire cat by the sculptor Julian Warren (also known as Metalgnu) looks down from a branch in a magnificent old mulberry.

The Mediterranean garden

Recently renovated, the rock garden beds contain many of the plants from the magnificent Flora Graeca published between 1806 and 1840 collected and described by the botanist John Sibthorp (1758-1796) and illustrated by Ferdinand Bauer (1760-1826). This was based on the writings of the Greek doctor Dioscorides in the first century AD.

The Medicinal garden

A must. Here you’ll find beds planted with 17th century medicinal plants, those that would have been used when the Physic Garden was founded. Also growing here are plants that provide modern medicines eg taxol from the bark of the Pacific Yew which is used to treat some cancers and salicin the active ingredient of willow from which aspirin was derived.

And don’t forget… the Jericho Coffee Traders

Outside the glass houses you’ll find the Jericho Coffee Traders' van, ideal for an excellent restorative coffee beside the Cherwell. And while on the subject of quenching thirst the Botanic Garden Boutique sells the Botanic Garden’s Physic Gin.

Entry to Oxford Botanic Garden costs £18 for adults; for further details and latest opening hours visit www.obga.ox.ac.uk

What else to do while you’re in Oxford

The Divinity School

The Divinity School is where oral examinations were held until the 19th century. People often visit these days because it was used as the Infirmary in several Harry Potter films but it's really worth seeing Potter or no Potter.

Designed by the English architect William Orchard in the late Gothic English Perpendicular style it has the most beautiful and intricately carved vaulted ceiling. Building started in 1427 but wasn’t completed for another 56 years, the delay, as ever, being caused by lack of funds.

The 455 bosses are carved with the initials of its funders and Edward IV gets the central position despite not having donated a penny. No doubt it was wise to keep the King sweet. Upstairs is the Duke of Humfrey’s Library. (See below)

For further details visit visit.bodleian.ox.ac.uk

Bodleian Old Library

The library you see today with its lavishly painted beams and individual reading areas — each beside a window to afford daylight — opened in 1602 but the library itself dates back to 1478 when work began to house a gift of more 281 books from Humfrey, Duke of Gloucester, the younger brother of Henry V. It finally opened in 1488. The library forms the second storey to the Divinity School (see above) and the original decoration would have been less colourful than it is today.

When Humfrey presented his gift the University owned only a handful of books — not surprising given that the first book printed in English in England had only recently come from William Caxton’s Westminster press (this was Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales,1476-77). The Reformation brought disaster and in 1550 all the books were removed by the Dean of Christ Church and many were burned.

The library fell into disrepair, the roof leaked and it was used as a storage space for the next 50 years. Only three of the original books survive. Its restoration was the project of Sir Thomas Bodley (1545-1613), a diplomat in the court of Elizabeth I, who wanted to end his career with a magnificent project. When the new library opened in 1602 it contained 2500 books. But Bodley’s foresight — he signed an agreement with the Stationers’ Company that a copy of every new book published should be sent to the library — means that the library has been increasing ever since.

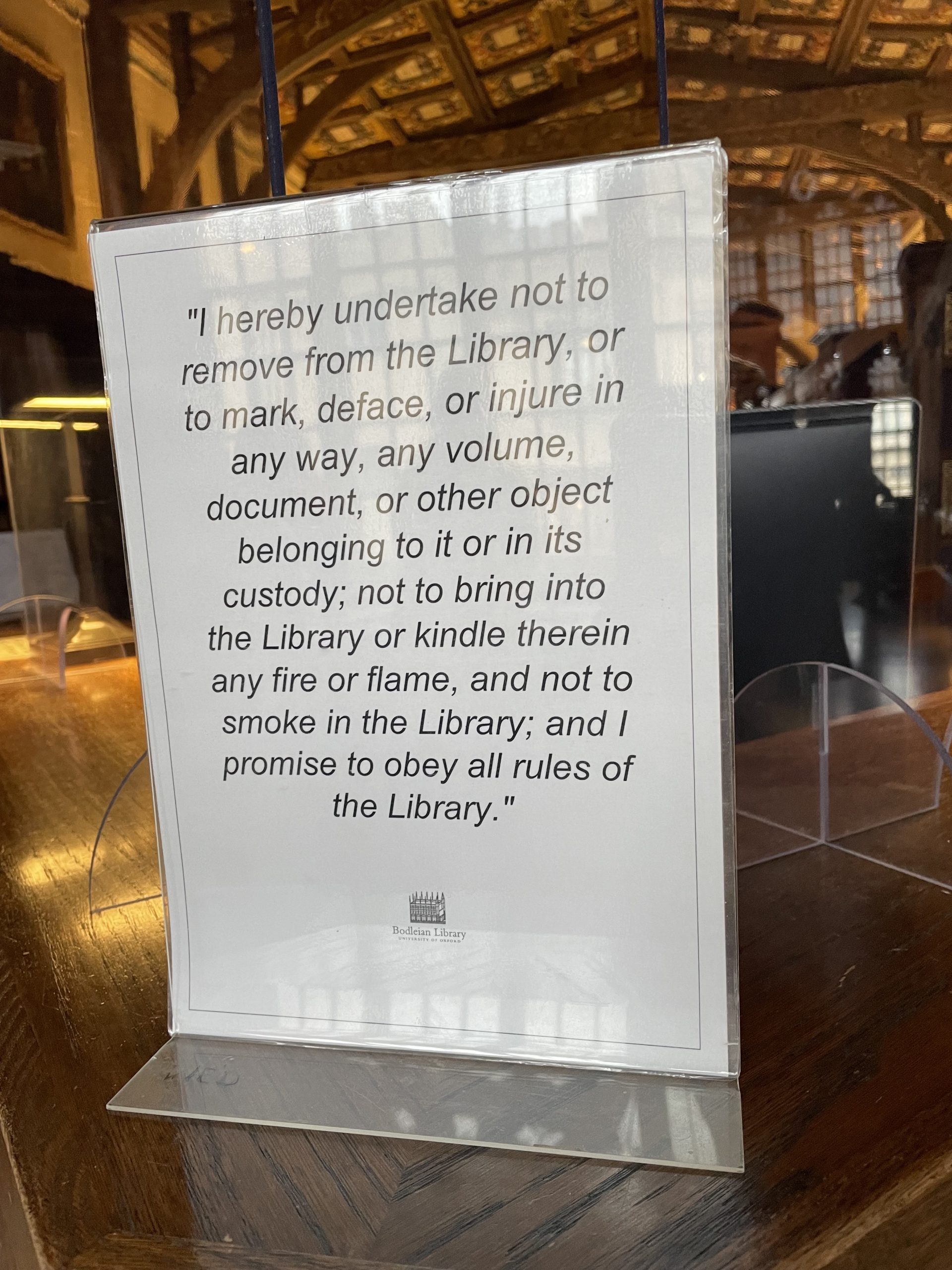

Up to 1500 new books arrive each week and the total number of publications (everything that has an ISBN) is heading towards 14 million books which are housed across Oxford, some underground and many in the Weston Library next door. In the new extension to the Old Library Sir Thomas had books stored on shelves. This galleried system was introduced from Europe with books stored in order of size, smallest at the top and volumes were chained until 1768. To this day students have to swear the following oath: …’Not to remove from the Library, nor to mark, deface, or injure in any way, any volume…not to bring into the Library or kindle therein any fire or flame, and not to smoke in the Library…’

For further details see visit.bodleian.ox.ac.uk

Weston Library

Exhibitions at the Weston Library (which has a nice cafe) draw on the rare books in the University’s collection. Chaucer Here and Now opens December 8th.

The Sheldonian Theatre

This was the first building designed by Sir Christopher Wren, and constructed between 1664 and 1669. Outside, the dramatic circle of Emperor heads was designed by the sculptor William Byrd (1624–c.1691). Inside, the ceiling by Robert Streater, Serjeant-painter to King Charles II is painted to look like a Roman theatre open to the sky and symbolises the Restoration.

For further details visit www.sheldonian.ox.ac.uk/visit

The Ashmolean

Always worth visiting because of the richness and breadth of its permanent collection, the corridors of the museum offer a great way to lose yourself for an hour or two in the centre of the city.

This where you’ll stumble across real treasures such as the famous Alfred Jewel to a prehistoric beaten gold sun disc. Explore further and you’ll stumble across less valuable but equally intriguing artefacts such as Guy Fawkes’ lantern, 17th century toadstone rings (worn to ward off poisoning) and the tombstone from Easton Neston ‘To the memory of PUG, who departed this life June 24, 1754, in the third year of her age’.

Book ahead to be sure of seeing its current exhibition The Colour Revolution: Victorian art, fashion and design. This explores the brilliance of colour the Victorians used in everything from a glowing stained glass window by Edward Burne Jones to ladies’ stockings (dyed cerise, blue, apricot and purple using newly discovered synthetic ‘aniline’ dyes made from coal tar) by way of arsenic green wallpapers and the Devonshire Parure: gleaming emeralds, sapphires and rubies worn by Countess Granville to the coronation of Tsar Alexander II in 1856.

And finally..

You can round off your visit with a slap up afternoon tea in the Ashmolean Restaurant on the roof of the museum.

For further details visit www.ashmolean.org

-

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagne

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagneAn upwardly mobile spaghetti Bolognese, lasagne al forno, with oozing béchamel and layered meaty magnificence, is a bona fide comfort classic, declares Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker Bowles

-

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025Thursday's Quiz of the Day asks exactly how popular Baywatch became.

By Toby Keel