Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Courtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

When the 18-year-old daughter of a grocer celebrated Boxing Day in 1943 with Spam salad, had a whisper of Hollywood glamour descended on the Lincolnshire town of Grantham?

Margaret Thatcher retained fond memories of that wartime Christmas spread: ‘We had friends in and I can quite vividly remember we opened a can of Spam luncheon meat,’ she recalled, decades later. ‘We had lettuce and tomatoes and peaches, so it was Spam and salad.’

Pink and flabby, greasy as Brylcreem and invented by Hormel & Co in Austin, US, during the Great Depression, Spam was a creative way of using pork shoulder meat, previously often discarded as waste because it took so long to cut from the bone.

On New Year’s Eve, 1936, company president Jay Hormel offered a $100 (£80) prize to his party guests if they could name his new product. One guest famously came up with Spam. Does it derive from ‘spiced ham’? ‘Spiced shoulder and ham’? Or perhaps ‘shoulder pork and ham’? The company has never explained. Perhaps the etymology simply got lost in a New Year’s hangover.

The best tinned food that I've tasted in two wars

Amelia Garrett, a Londoner and Spam-fan

Spam was available, if in short supply, in British grocer’s shops from 1941. However, by 1942, it was Spam-with-everything, courtesy of the Lend-Lease programme of aid shipments from America to her allies — and weren’t we grateful.

Spam was ‘the best tinned food that I’ve tasted in two wars,’ gushed Amelia Garrett from London in fan mail to Hormel & Co. The Rochdale Observer suggested, tongue in cheek, that it would bring a taste of ‘the high, hot-dog life of Hollywood’ and that the local Co-op (and also, perhaps, two Grantham grocer’s shops belonging to Alfred Roberts, father of Thatcher) would be imbued with the ‘glamour of El Morocco’.

To the war-weary British, Spam seemed symbolic of the American lifestyle and positively exotic. We ate Spam omelette (made with dried eggs), Spam fritters, Spam-in-the-hole, Spam-with-everything. Newspapers and women’s magazines vied to give tips and recipes, as if a woman’s biggest contribution to the war effort was making Spam palatable. Even escalope Amigoni, with its whiff of la dolce vita, was, in fact, breadcrumbed Spam with turnip and carrots braised in margarine.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

As it wasn’t rationed in the same way as sugar or tea, Spam could be purchased under the points system, which allowed shoppers some freedom of choice — those who couldn’t stomach it could opt for cornflakes or pilchards instead — although a 12oz can cost eight points, which was half a monthly allowance.

London restaurants even served gussied-up, camouflaged Spam. In 1944, Simpson’s in the Strand, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead; escalope du Barry, at a restaurant in Soho, sounds like haute cuisine, but turned out to be sliced Spam in cauliflower sauce. At the Green Midget Cafe in Bromley — scene of the Monty Python sketch that immortalised Spam for a new generation — you could have Spam, egg, Spam, Spam, bacon and Spam or lobster Thermidor aux crevettes with a Mornay sauce garnished with truffle pâté, brandy, a fried egg on top and Spam. ‘I don’t want ANY Spam,’ screeched comedian Graham Chapman.

‘As the war dragged on, people got really sick of it,’ explained the food historian Kelly Spring, author of Spam, A Global History (Reaktion Books, £12.99). ‘Spam wasn’t cool — out of the can, it’s a weird, jiggly meat.’ The recipe that most intrigued her, although she wasn’t brave enough to re-create it, she says, was tripe and Spam pie from ‘Lady Edith’s Hints’, published in a Belfast newspaper in 1942: the filling was made from 1lb of cooked tripe and two or three slivers of Spam.

Eventually, a backlash ensued against the tinned meat — there was simply too much of it. A Glaswegian man was fined for beating his wife after she gave him a meagre Spam sandwich to take to work. ‘It was the only thing I could get on a Monday,’ she claimed in her defence.

‘Real men’, it seems, didn’t eat spam. ‘There’s this idea that Spam was good enough for women, okay for their needs,’ notes Spring. ‘However, “real” meat was primarily for men, who had “protein priority”.’

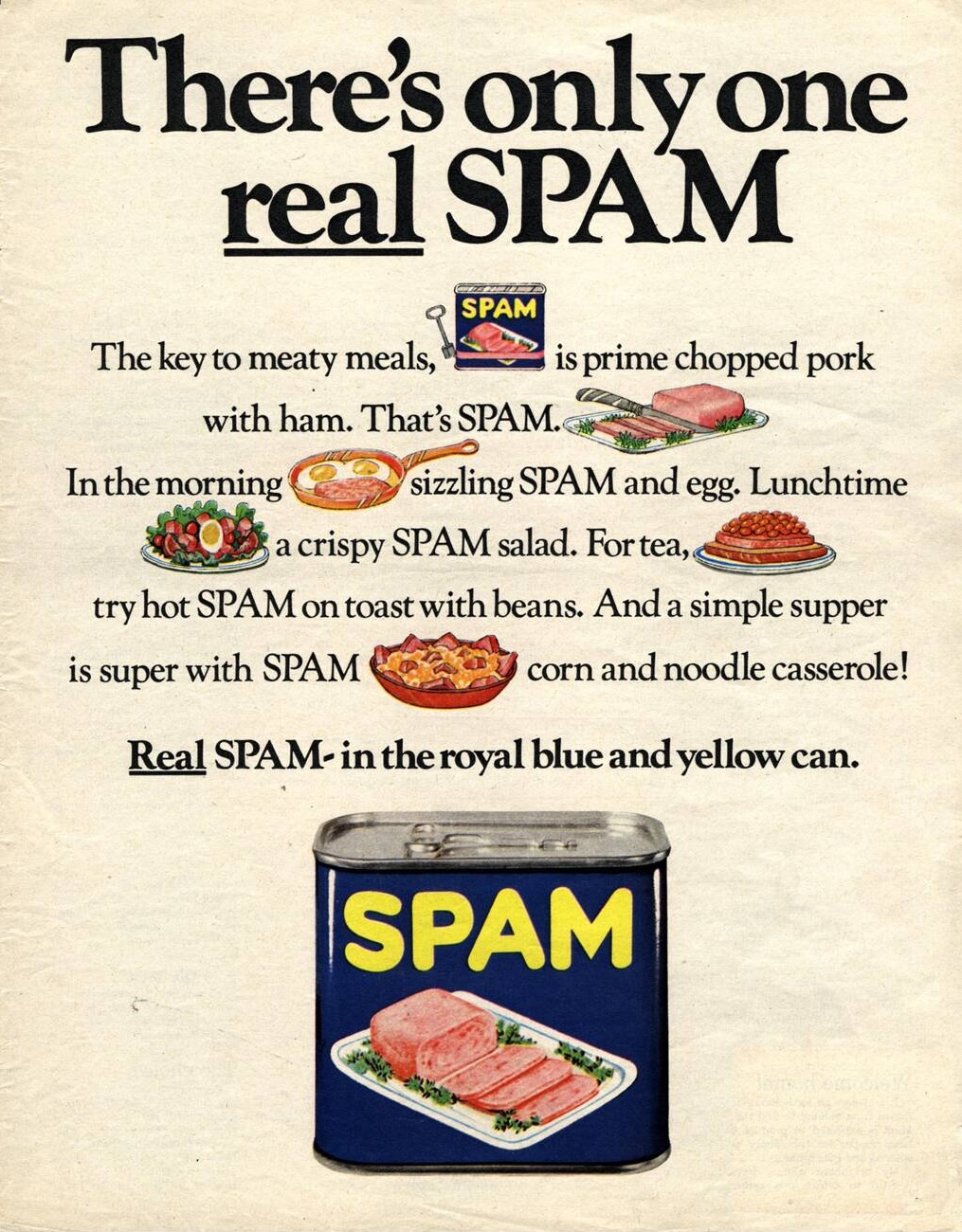

A 1980s Spam advert from a British magazine

Unsolicited spamming

Where US soldiers went, so did Spam. The biggest market today, outside of America, is South Korea. The devastation of the Korean War brought starvation in its wake and hunger drove people to scavenge for food scraps discarded by US military camps. The result was budae-jjigae, which translates as ‘army stew’—a hot-pot made from whatever was at hand: Spam, baked beans, hot-dog sausages, ramen noodles, tofu and American cheese, made palatable with kimchi, gochujang (chilli paste) and gochugaru (chilli flakes).

To an older generation it was tinged with shame, but since the 1980s, when Spam became widely available in shops, budae-jjigae has become a national comfort food, served in restaurants where diners cook their own choice of ingredients in a bubbling communal pot at the table. In recent times Spam has transcended its association with poverty to become a luxury item, sold in pricey gift sets that are popular presents at Lunar New Year and the Harvest Moon Festival.

In Hawaii, military presence had a lasting impact on local diet and the state is now the US’s top consumer of Spam. One of the most popular dishes is musubi: Spam and rice rolled in seaweed, like sushi.

A female war worker wrote to The Manchester Guardian after ordering a pie and a cup of tea for her cafeteria lunch: ‘You can’t have a pie,’ replied the attendant, with the faintest hint of reproach in her voice. ‘Pies are scarce today and we are reserving them for the gentlemen’s buffet. But,’ she added helpfully, ‘you can have a Spam sandwich.’

‘I was served with a really lady-like Spam sandwich,’ recalled the disgruntled customer, wondering why a woman with a full-time war job and a house to run, ‘should be denied priority for the benefit of a business gentleman who probably had a wife in the background planning his evening meal.’

Classless (because everybody ate it), Spam was to become a nostalgic, slightly embarrassing joke after the war. Council tenants taunted the aspirational middle-classes living in ‘Spam Valley’, homeowners so heavily mortgaged that they could only afford canned meat.

In the Armed Forces, however, Spam continued to have multifarious uses. Soldiers greased their guns and waterproofed their boots with it and even fashioned candles by inserting a twisted rag into empty cans. During the Korean War, US soldiers inked card faces onto slices of Spam, which lasted through three months’ worth of poker games, although one veteran complained: ‘We lost the deuce of diamonds when a dog ate it.’

Spam has proved such a mainstay of army rations it was reported that British soldiers in Afghanistan survived for six weeks on a diet of Spam carbonara, Spam stroganoff and Spam stir-fry, after the Taliban shot down a helicopter bearing fresh food supplies. That was in 2010—not long after we finally cleared our Lend-Lease debt to America, making the final payment of $83 million (£66.6 million) in December 2006. Although it was seen as a neighbourly gift, clearly there’s no such thing as free Spam.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Sanderson's new collection is inspired by The King's pride and joy — his Gloucestershire garden

Sanderson's new collection is inspired by The King's pride and joy — his Gloucestershire gardenDesigners from Sanderson have immersed themselves in The King's garden at Highgrove to create a new collection of fabric and wallpaper which celebrates his long-standing dedication to Nature and biodiversity.

By Arabella Youens

-

The coveted Hermès Birkin bag is a safer investment than gold — and several rare editions are being auctioned off by Christie’s

The coveted Hermès Birkin bag is a safer investment than gold — and several rare editions are being auctioned off by Christie’sThere are only 200,000 Birkin bags in circulation which has helped push prices of second-hand ones up.

By Lotte Brundle

-

Never leave a bun behind: What to do with leftover hot cross buns

Never leave a bun behind: What to do with leftover hot cross bunsWhere did hot cross buns originate from — and what can do with any leftover ones?

By Amie Elizabeth White

-

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter Weekend

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter WeekendAsparagus has royal roots — it was once a favourite of Madame de Pompadour.

By Melanie Johnson

-

Gill Meller's recipe for a seasonal new potato omelette, with smoked garlic, onions and Cheddar cheese

Gill Meller's recipe for a seasonal new potato omelette, with smoked garlic, onions and Cheddar cheeseBy Gill Meller

-

How to make a rhubarb and Swiss meringue cake that's almost too pretty to eat

How to make a rhubarb and Swiss meringue cake that's almost too pretty to eatMake the most of the last few stems of forced rhubarb.

By Melanie Johnson

-

The prettiest Easter eggs for 2025

The prettiest Easter eggs for 2025Warning: Don't read if hungry.

By Rosie Paterson

-

An Italian-inspired recipe for lemon-butter pasta shells with spring greens, ricotta and pangrattato

An Italian-inspired recipe for lemon-butter pasta shells with spring greens, ricotta and pangrattatoSpring greens are just about to come into their own, so our Kitchen Garden columnist reveals exactly what to do with them.

By Melanie Johnson

-

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?As April 1 looms, Martin Fone tells the tale of one of the finest stunts ever pulled off.

By Martin Fone

-

Tom Parker Bowles's Tour de Fromage, from creamy Camembert and spicy, pungent Époisses to the 'mighty, swaggering Roqueforts'

Tom Parker Bowles's Tour de Fromage, from creamy Camembert and spicy, pungent Époisses to the 'mighty, swaggering Roqueforts'The chef and food writer Tom Parker Bowles picks out his all-time favourite cheeses from across the Channel in France, from buxom, creamy Camembert to mighty, swaggering Roquefort.

By Tom Parker Bowles