Curious Questions: How do you make the perfect slice of toast?

Jonathan Self is toast-mad. His entire family is toast-mad. He's spent his life looking for the ultimate way of making the nation's favourite snack. Here's what he suggests you do.

Challah bread, toasted, lightly buttered with a smoked salmon, caper and ground-pepper topping and a squirt of lemon juice (my maternal grandmother). Thin wholemeal bread with its crusts cut off, toasted, imperceptibly buttered, cut into strips (or toast soldiers) and served with a boiled egg (my paternal grandmother). Thin wholemeal bread with its crusts cut off, toasted, imperceptibly buttered and spread with Gentleman’s Relish (my grandfather). A baguette, sliced lengthways, toasted until dark brown and smeared with crushed garlic (my French nanny). Sliced pan, soaked in melted butter, generously sprinkled with sugar and cinnamon and grilled to create a slightly rough sweet outer and soft doughy centre (my mother). Crusty, thick slices of white bloomer covered with what can only be described as slabs of salted butter on which lavish quantities of coarse-cut Oxford marmalade have been heaped (my father).

I grew up in a family of toast lovers. Each had their favourite recipe and each prepared it in their own unique way. My mother, for example, would recite every step out loud as she worked: ‘Three tablespoons of granulated sugar, two teaspoons ground cinnamon, a pinch of salt…’ She was quick and confident and could produce a plate of comforting, cut-up cinnamon toast (always triangles, never squares) faster than it took to boil the kettle for tea.

My father, on the other hand, challenged Nigel Slater’s claim that it is impossible not to love someone who makes toast for you. He cut the bread too thick. He cut the bread too thin. He dropped the bread. He dropped the bread knife. He debated whether to make it on the Aga (‘could taste a little smoky for you’) or under the gas grill (‘could taste a little bland for you’). He checked it every few seconds and then, at the crucial moment, forgot about it completely, so that it caught fire. He tried to scrape it, burnt his fingers, reluctantly confined the flaming slices to the compost bin — where they would continue to emit plumes of black, acrid smoke — swore and started again.

Unsurprisingly, my earliest memories of food are toast related. If I had to choose a last meal, it would be buttered toast, consumed in bed (never mind the butter on the pillows or the crumbs in the sheets) and served with a pot of Darjeeling. I associate it with security, contentment, solace, succour and, as I can always find room for one more slice — how right Tonia George was when she commented that ‘toast has never been a friend of restraint’ — satiety.

It is the food I turn to when I am happy and when I am sad, when I am only vaguely peckish and when I am completely famished. It is also what I eat when I feel poorly, because toasting bread breaks down the starch, making it easy to digest.

Toast is convenient and humble: as equally at home in the most luxurious of mansions as it is in the poorest of cottages. It is, in short, the food of everyman, everywoman and (in this house) everydog.

For such an essentially simple and uncomplicated food, toast has a long and curiously fascinating history. The first reliable evidence of a baker managing to get their bread to rise (no leavened bread, no toast) comes from Egypt, about 4000BC, and presumably it wasn’t long afterwards that someone hit on the brilliant idea of holding the result over a fire to preserve it. We owe its name, however, to the Romans, who called it tostum, from torrere: to scorch or burn.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Passing over the Ancients’ recipes for tomàquet and crème fraiche crostini and ignoring the Dark Ages and the invention of pain perdu (lost, that is stale, bread), also called French toast (which isn’t toast at all), the next significant event occurred when medieval gourmands revived the Roman practice of putting burnt toast into bad wine in order to improve its taste and texture. Instead of burning the toast, they added spices to it and used the result to flavour beer and other drinks.

This custom lasted for several centuries. In Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor, for example, published in 1602, Falstaff says: ‘Go fetch me a quart of sack; put a toast in’t.’ Indeed, the symbolic dunking of toast in a drink is where the expression ‘to toast someone’ is believed to have originated.

The making of toast has always involved a fair amount of ritual. Early toasting forks have been found in both Egyptian and Roman archaeological sites, but it wasn’t until the 19th century that new and ingenious ways of toasting bread were developed. The first of these was a coal-powered range cooker with a built-in toast plate — a heavy iron rack that sat over the fire grate. Widely used from the 1850s onwards, it must have branded a sort of chequerboard pattern on the toast.

The first electric toaster was invented in 1893, but, as the iron wiring tended to melt, it wasn’t a great success. In 1905, Albert Marsh created nichrome, the filament wire needed to toast bread safely and, in 1906, the first patent for an electric toaster was filed. Since then, we have seen the invention of pop-up toasters, toasters that can make six slices at once, toasters with conveyor belts, toasters with timers, toasters with sensors and even touch-screen toasters. All these various devices are designed to prevent something deeply unpleasant: soggy toast.

The way my father fussed when toasting is by no means unusual. Regardless of the method employed, it takes an exceptionally calm and collected person not to keep checking and rechecking the toast as it is being made. I doubt that even James Bond was able to resist interrupting what scientists call the ‘Maillard reaction’, the process of non-enzymatic browning, caramelisation and pyrolysis that causes the surface of the bread to become crisp and dry, at the same time as leaving the inside warm and moist.

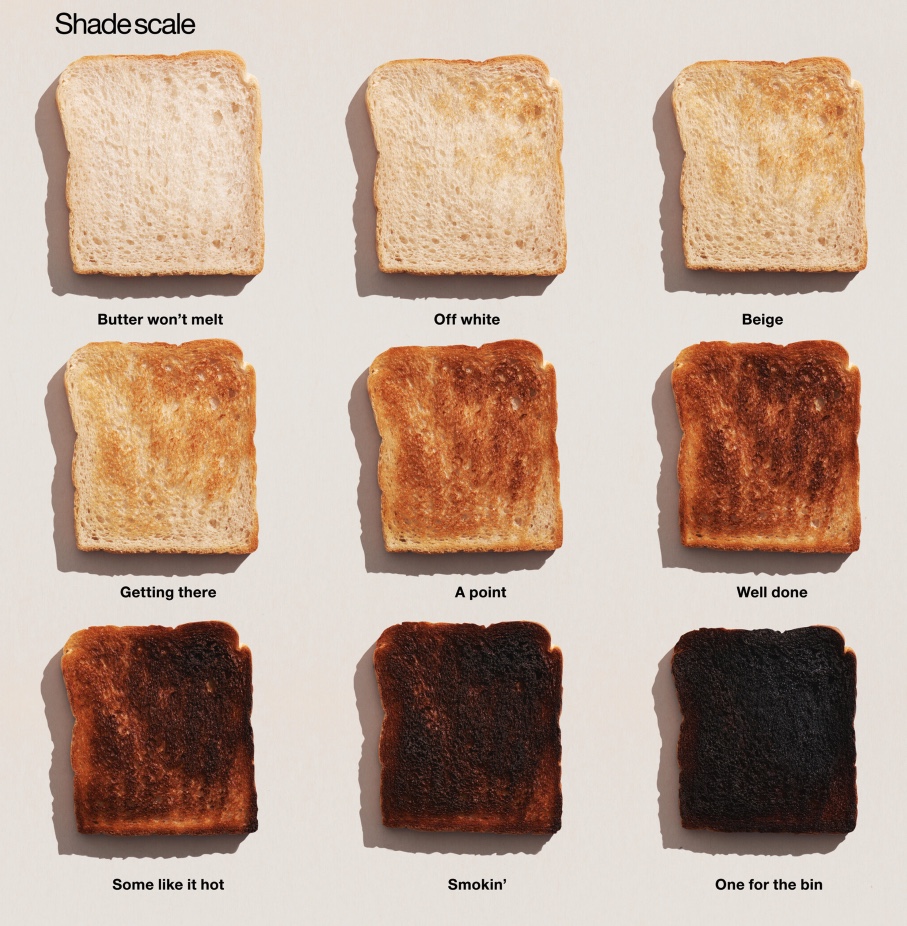

Purists say that if freshly prepared toast is placed onto a plate, the steam in the centre is unable to escape, causing the whole piece to become soft and inedible. We are talking here about ‘rackers’: people who would rather have stiff, cold (impossible to butter) toast over moist, hot (oh, so easy to butter) toast. Of course, everyone has their own preferences — colour, temperature, thickness, with or without crust — but I’ll eat croissants for breakfast before I ever countenance the use of a toast rack.

Toast may be an unassuming foodstuff, but it engenders remarkably strong emotions. For my own part, it makes me nostalgic. I don’t think it is any coincidence that toast features strongly in children’s literature. When Lewis Carroll’s Alice tries the little bottle labelled ‘drink me’, she discovers ‘it had, in fact, a sort of mixed flavour of cherry-tart, custard, pineapple, roast turkey, toffy, and hot buttered toast’. In Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, ‘the smell of that buttered toast simply spoke to Toad, and with no uncertain voice… it talked of warm kitchens, of breakfasts on bright frosty mornings, of cosy parlour firesides on winter evenings, when one’s ramble was over and slippered feet were propped on the fender; of the purring of contented cats, and the twitter of sleepy canaries’. Describing Mary Poppins, Pamela Lyndon Travers said that a ‘faint flavour of toast always hung about her so deliciously’. The point is, we are raised to perceive toast in a certain way.

You may recall the furore a few years ago when a journalist attacked ‘young people ordering smashed avocado with crumbled feta on five-grain toasted bread’, arguing that they should be saving to buy a house instead. The young fought back, pointing out that even if they forwent this simple pleasure, it would take them several hundred years to buy even a modest flat.

Toast, with its infinite variety and tastes, or home ownership with its responsibilities and bills? I know which I would choose. Toast is, after all, the best thing since sliced bread.

After trying various jobs (farmer, hospital orderly, shop assistant, door-to-door salesman, art director, childminder and others beside) Jonathan Self became a writer. His work has appeared in a wide selection of publications including Country Life, Vanity Fair, You Magazine, The Guardian, The Daily Mail and The Daily Telegraph.

-

Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasures

Diamonds are everyone's best friend: The enduring appeal of one of Nature's sparkliest treasuresEvery diamond has a story to tell and each of us deserves to fall in love with one.

By Jonathan Self

-

RHS Chelsea Flower Show: Everything you need to know, plus our top tips and tricks

RHS Chelsea Flower Show: Everything you need to know, plus our top tips and tricksCountry Life editors and contributor share their tips and tricks for making the most of Chelsea.

By Amie Elizabeth White