'One of the most amazing things in terms of food in this country' — How a tower of thorns makes salt

Made with wind, sea and thorns on the wild west coast of Scotland, Blackthorn Salt brings surprising health benefits, as well as being a unique example of sustainable craftsmanship.

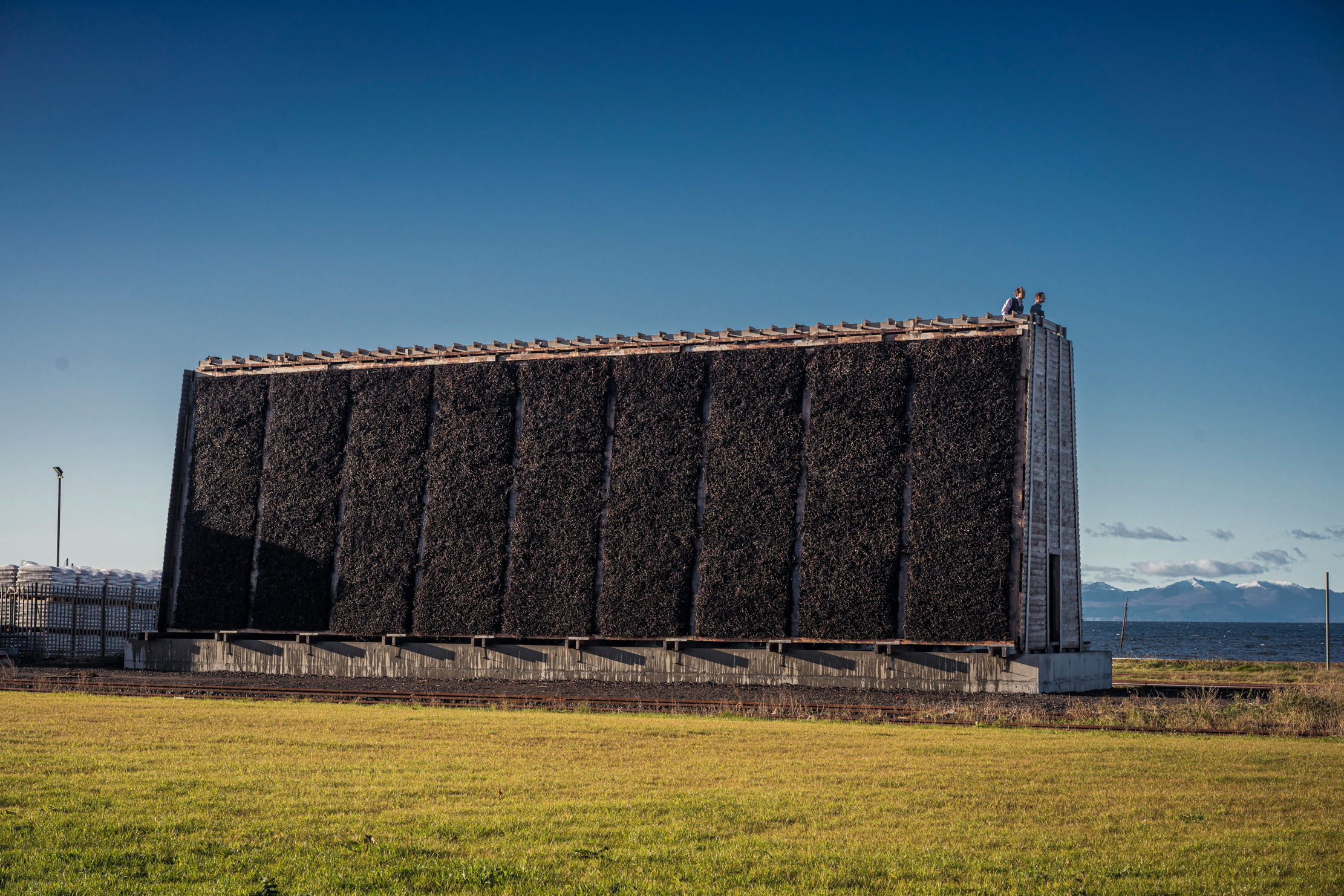

On the west coast of Scotland, facing out across the Firth of Clyde towards the Isle of Arran, there stands a wall of thorns. It is manmade, but otherworldly, like a vision from a Gothic fairy tale. Its dark tangle of barbs reaches up to a height of 30ft and stretches more than 100ft across. Is it an art installation? A giant instrument of torture on the outskirts of Ayr? The correct answer is far simpler: it makes salt.

The history of salt production in Scotland dates back almost a millennium. Before the arrival of refrigeration, the mineral gave a vital means of preserving meat and other foodstuffs. Sea salt was, therefore, harvested along both coasts of the country — using salt pans, shallow containers in which seawater could be heated by fire and evaporated — and, by the end of the 18th century, the commodity had become Scotland’s third most valuable export, behind only wool and fish. Then came a steep decline, as demand waned and the market was overtaken by cheaper rock salt. The last Scottish salt-pan works was closed in 1959.

Back to the present-day Ayrshire coast, where Gregorie and Whirly Marshall are quietly changing the narrative. The husband-and-wife owners of Blackthorn Salt are responsible not only for the prickly monolith on the foreshore, but for reintroducing the sea-salt industry to this corner of the country. It’s been a labour of love — and a long one. ‘We actually launched in 2020, during lockdown, but it wasn’t as if it was a project that came from pandemic boredom,’ laughs Mrs Marshall. ‘The planning and design process had taken the best part of 20 years.’

The graduation tower, to give it its proper name, works in the following way. Sieved seawater is piped up to the summit of the structure, then trickled, via wooden taps, down the tower’s web of spiny branches. Each droplet makes its own haphazard journey through the thicket, zigzagging across spike and branch, flowing from twig to thorn.

The aim of this slow journey from top to bottom is to give ample time for the droplets to be evaporated by the breeze coming in from offshore. By the time the water reaches ground level, it has become an ultra-salty brine ready for crystallisation. The process is highly sustainable, requiring only wind and seawater to function. It’s also highly effective. All that remains is for the brine to be run through an even finer sieve before being transported to the next-door pan house, where a gentle heat draws out the crystals. The results are sparkling, in more ways than one.

'The crystals inside are now relied on by more than 20 Michelin-starred restaurants'

The A-frame skeleton of the tower was constructed from local larch and Douglas fir — Mr Marshall, as well as previously being involved in the salt-import trade, has a background as an architect. The bushels themselves are, as the company’s name suggests, cut from blackthorn. ‘Salt actually cures wood, so the blackthorn itself is really hardy,’ explains Mrs Marshall. ‘We think it will need to be replenished every seven to 10 years.’ In preparation, they’ve planted 80 acres of blackthorn bushes nearby.

Similar salt towers were historically built in Germany and Poland. Some can still be found in spa towns, where the saline air they emit is said to benefit people with bronchial issues. The Scottish structure, by contrast, is now the only functioning salt-making tower in the world, requiring zero kilojoules of energy to operate and creating a unique culinary product. ‘Every crystal comes from pure seawater,’ adds Mrs Marshall.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

This brings us to the salt itself. It has a particularly high calcium content when compared with other sea salts, but also contains enough magnesium and potassium to balance the sweetness. To give you a steer as to its quality, you’ll find it stocked in Harrods, Selfridges and Fortnum & Mason. The boxes are embossed with two Great Taste stars and the crystals inside are now relied on by more than 20 Michelin-starred restaurants. Chef James Martin has praised the product as ‘one of the most amazing things in terms of food in this country’. That’s some impact for a venture that is only a shade over three years old.

Mrs Marshall recommends sprinkling a small pinch on a halved, good-quality tomato as a taste test. I do as she suggests. The salt has what she calls ‘that crucial crunch factor’, but, more than that, it teases out flavours that linger in the mouth for minutes. Mrs Marshall starts mentioning eggs, steak and chocolate, but, in truth, I’m won over already.

Only two people work on the graduation tower — Mr Marshall and fellow salter Malky McKinnon — and the process involves no seeding, adding or bleaching. Even the packaging uses only sustainably sourced cardboard. ‘We are, each of us, wholeheartedly proud of what we do,’ summarises Mrs Marshall. There’s nothing thorny about understanding why.

Chillingham Castle: 'Curiosity and beauty' at a spectacular castle that survived ruin by the skin of its teeth

Chillingham Castle, Northumberland — the home of Sir Humphry Wakefield Bt and the Hon Lady Wakefield — is a castle saved from

‘I hated it at first’: Britain’s top caviar supplier on eggs, royal clientele and the future of Beluga sturgeon

Helen Rebanks: Farming, food, the meaning of life... and dogs stealing birthday cakes

Helen Rebanks, the bestselling author who became Britain's favourite farmer's wife, joins the Country Life podcast.

The re-making of Notre Dame: An extraordinary achievement by any measure

Country Life's cultural columnist Athena on the astonishing progress being made in the rebuilding of Notre-Dame de Paris — and how

Ben Lerwill is a multi-award-winning travel writer based in Oxford. He has written for publications and websites including national newspapers, Rough Guides, National Geographic Traveller, and many more. His children's books include Wildlives (Nosy Crow, 2019) and Climate Rebels and Wild Cities (both Puffin, 2020).