Hedgerow Harvest

Blackberries are all well and good, but the hedgerows are brimming over with less well-known delights at this time of year.

Most people, mindful of what their mother told them about wild berries, pick blackberries and little else, but there is so very much more. There are crab apples, sloes, haws, plums, damsons, bullaces, elderberries, dewberries, bilberries, redcurrants, rowanberries, sea buckthorn berries, hazelnuts, sweet chestnuts and more. I love them all (with the possible exception of rowan berries, which taste unmistakeably of sick) and collect them all, but I do have my favourites.

The elder is one. It’s an untidy-looking shrub, with spreading stems that often lean lazily on other woody plants and frequently simply fall over. Yet it’s a strangely attractive tree and I’m always pleased to come across one. I learned from my grandmother, a Wiltshire country girl, that I should never bring the wood into the house and must always apologise if I accidentally break the brittle branches (I always say sorry, still).

In late summer and early autumn, the branches hang heavy with their corymbs of deep-purple berries. Really, elderberries are one-trick wonders in the kitchen you can make elderberry wine with them and little else. Cynical as I am about country wines, this is one that every home-brewer should try. It’s good for you, too: the 16th-century herbalist Gerard tells us that it’s useful for ‘such as are too fat and would faine be leaner’.

There seem to be more apples in the hedgerow than in gardens and orchards. Most, the wilding apples, are the result of felicitous littering and are near random in their qualities. Appearance and provenance count for nothing, however you’ll just have to try one to see if it’s worth using. Crab apples are a different (although much hybridised) species and are confined to open woodlands such as the New Forest and internal field hedges where they were planted during the late enclosure period. They are all but inedible raw, but can be put to endless uses in the kitchen notably to add tannin level and texture to dessert apples destined for the cider press.

Almost any apple can be used to make a juice, a jelly and, best of all, when mixed with other hedgerow fruits, a fruit leather. You simply stew the fruits, strain through a sieve, dissolve in some sugar and dry the resultant sweet purée thinly spread on baking parchment on a tray in a very low oven. Delicious.

Past the crab apples that grow along the path to the hill visible from my office is a straight hedge made entirely of blackthorn bent, gnarled and black in winter which I used to tell my daughters was a goblin army frozen forever by a benign local witch. The blackthorn, of course, produces sloes and this is my favourite spot to pick them. The sloe is another one-recipe fruit (although there is wine and jelly, too): sloe gin. There’s nothing to making it you just put any ripe sloes in a jar, sprinkle on a substantial amount of sugar, add gin and leave for six months before decanting.

Some wild fruits are much better enjoyed on the hoof. The wild raspberry is one and the bilberry, cousin of the commercial blueberry, another. It is a fruit of late summer and autumn, which always reminds me of the Quantock Hills, where my wife and I used to go on fungus forays. Distracted from the fungi, we would crouch, uncomfortable but content, among the tiny heathland shrubs, stuffing our faces like children. Each bush yields only a handful of bilberries, so immediate gratification is the only sort that will suffice.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

We still go out on fungus forays, but now it’s to the New Forest. The distraction there is not the bilberry, but the sweet chestnut. Although most trees in any year produce nothing but empty husks, a walk through the woods in mid October will sometimes find one that has decided that, this year, it will do its duty.

Christmas aside, the chestnut is a seriously underused resource on these shores. There are, in fact, a great many things that can be done with a chestnut, but my favourite use is as a flour. Added to the regular wheaten stuff in pastries, cakes and bread, it provides an otherwise unthought-of richness and a roux made with chestnut flour elevates the gravy of a game pie to glory.

The winter months are a restless time for the forager, as few fruits or nuts linger beyond mid November, but there is plenty to look forward to in the spring and one has a comforting and well-stocked larder full of dried mushrooms and seaweed, jams and fruit leathers. And, best of all, there is always something to drink.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?The team behind London's first mixed-use ‘wellness village’ says it has the magic formula for tempting workers back into offices.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

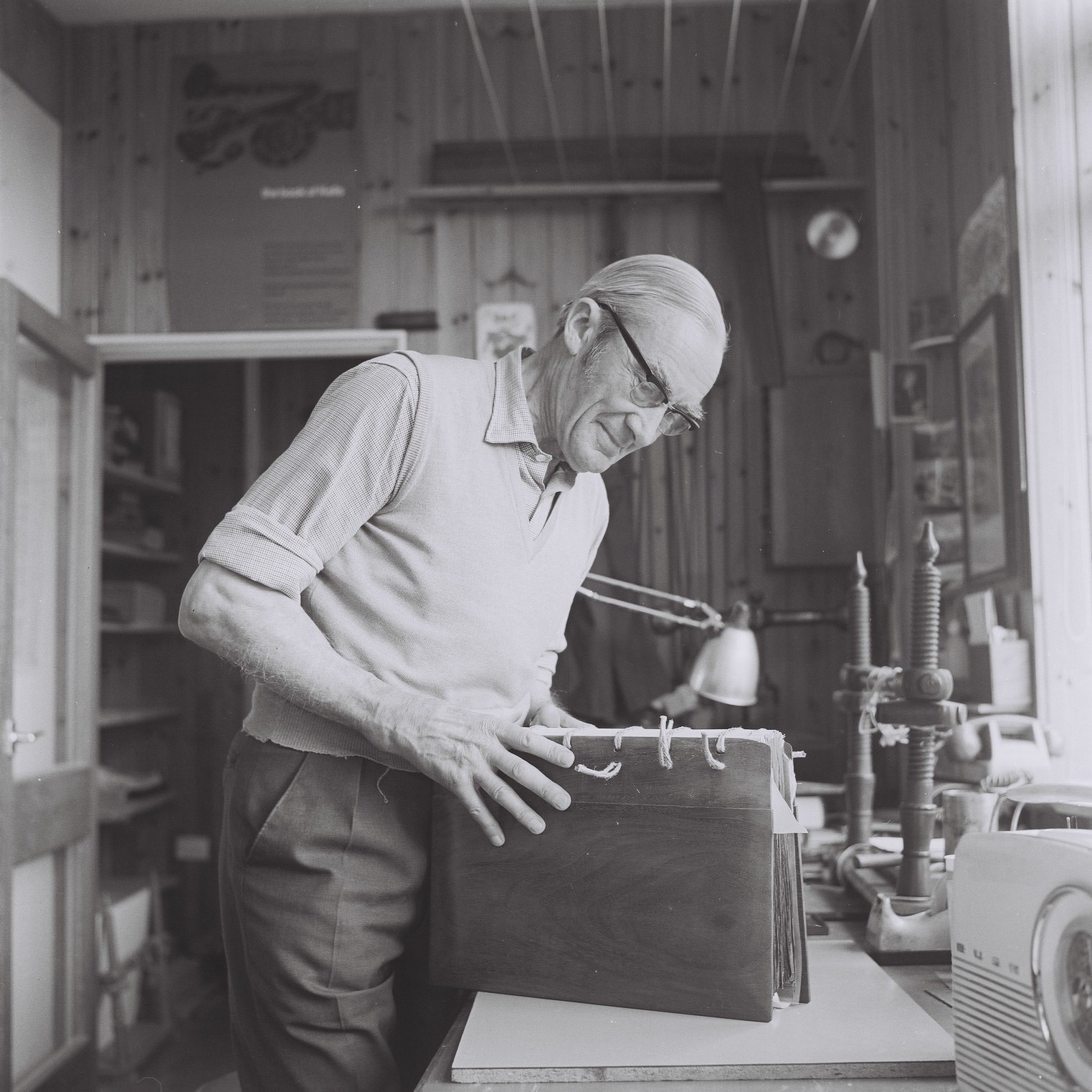

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani