Curious Questions: Why was absinthe banned?

Absinthe is almost unique among alcoholic spirits for having been outlawed in even some of the world's most liberal countries — but how did that happen? Martin Fone traces back the story to find the tales of debauchery, hallucination and even murder that once gave the drink its bad name — and looks at how it's returned to prominence.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It might just be a case of absinthe makes the heart grow fonder. After a century languishing in the doldrums, a victim of the mythology that surrounded it, absinthe is now one of the trendiest spirits in town with over 200 brands to choose from and a global market value worth £113 million in 2023. The UK even has its first absinthe distillery, the London-based Devil’s Botany.

Made by distilling a neutral base spirit with macerated herbs and spices, principally wormwood, which, together with anise, gives absinthe its characteristically bitter liquorice flavour. Its electric-green colour comes from an infusion of fresh herbs prior to bottling. With an ABV (alcohol by volume) percentage ranging between 45 and seventy-four per cent, its strength combined with its mix of ingredients has given it its infamous potency.

Absinthe’s spiritual home is the village of Couvet in Switzerland’s Val-de-Travers region, a place of refuge for French loyalists escaping from the terrors of the Revolution. One such was Dr Pierre Ordinaire, a retired physician. Wormwood, Artemisia absinthium, had for centuries been used as a medicinal herb to treat indigestion and stomach disorders, but it was acerbic, a characteristic reflected in its botanical name, derived from the Greek apsinthion, meaning undrinkable.

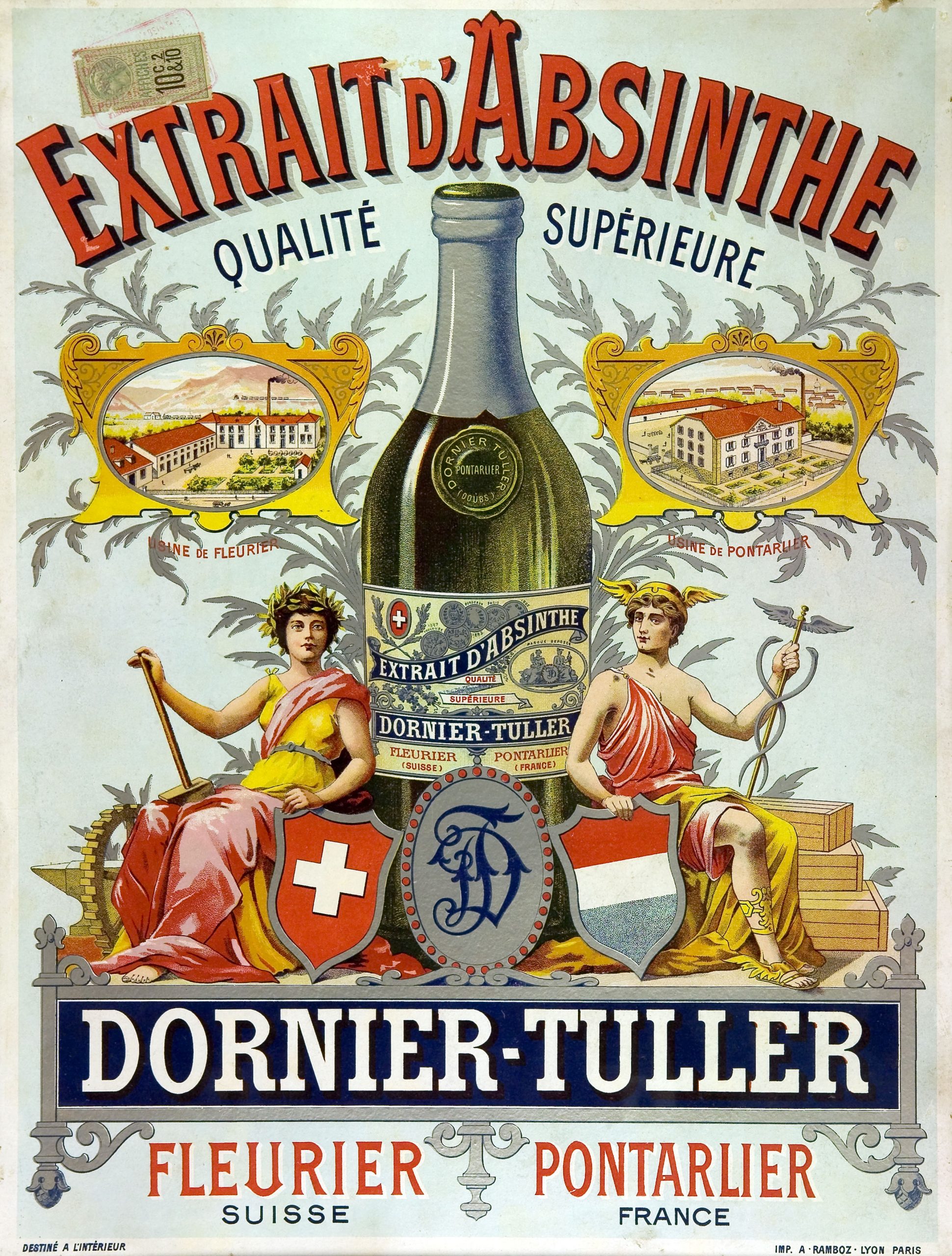

Ordinaire set about developing a palatable wormwood-based elixir and by 1792, so the story goes, had produced a potion made by macerating fifteen botanicals in grape spirit, which he called Extrait d’Absinthe. On his death he left the recipe and a sum of money to his housekeepers, the Henriod sisters, who sold the drink as Dr Ordinaire’s Absinthe.

However, an advertisement in a Neuchatel newspaper from 1769 for ‘Bon Extract d’Absinthe’ suggests that the Henriod sisters were making a wormwood-based drink well before Ordinaire had arrived in Couvet and, to cloud the waters further, one Abram-Louis Perrenoud had started distilling absinthe commercially as a beverage rather than an elixir in the village sometime around 1794.

What is clear is that an émigré French lacemaker, Major Dubied, commercialised the production of absinthe through a combination of strategic marriage alliances and entrepreneurial acumen, marrying his daughter off to Perrenoud’s son, Henri-Louis, in 1797, and, a year later, establishing Dubied Père at Fils after acquiring the recipe either from Perrenoud or, possibly, the Henriod sisters. In 1805 Henri-Louis, after changing his surname to Pernod, set up his own absinthe distillery under the name of Pernod et Fils, just inside France in Pontarlier, a move that avoided paying taxes at the border with Switzerland.

Absinthe’s distinctive flavour made it a welcome addition to the menus of French cafes and bars. Its popularity was further strengthened in the 1840s when French army doctors prescribed it as a protection against fevers, malaria, and dysentery during the Algerian campaigns. The destruction of the country’s vineyards by phylloxera from 1862 meant that cheap wines and brandies were no longer available, and even more drinkers turned to absinthe. At the height of its popularity, 36 million litres were being produced a year, twenty-six alembics at Pernod et Fils’ distillery accounting for 20,000 litres a day alone.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

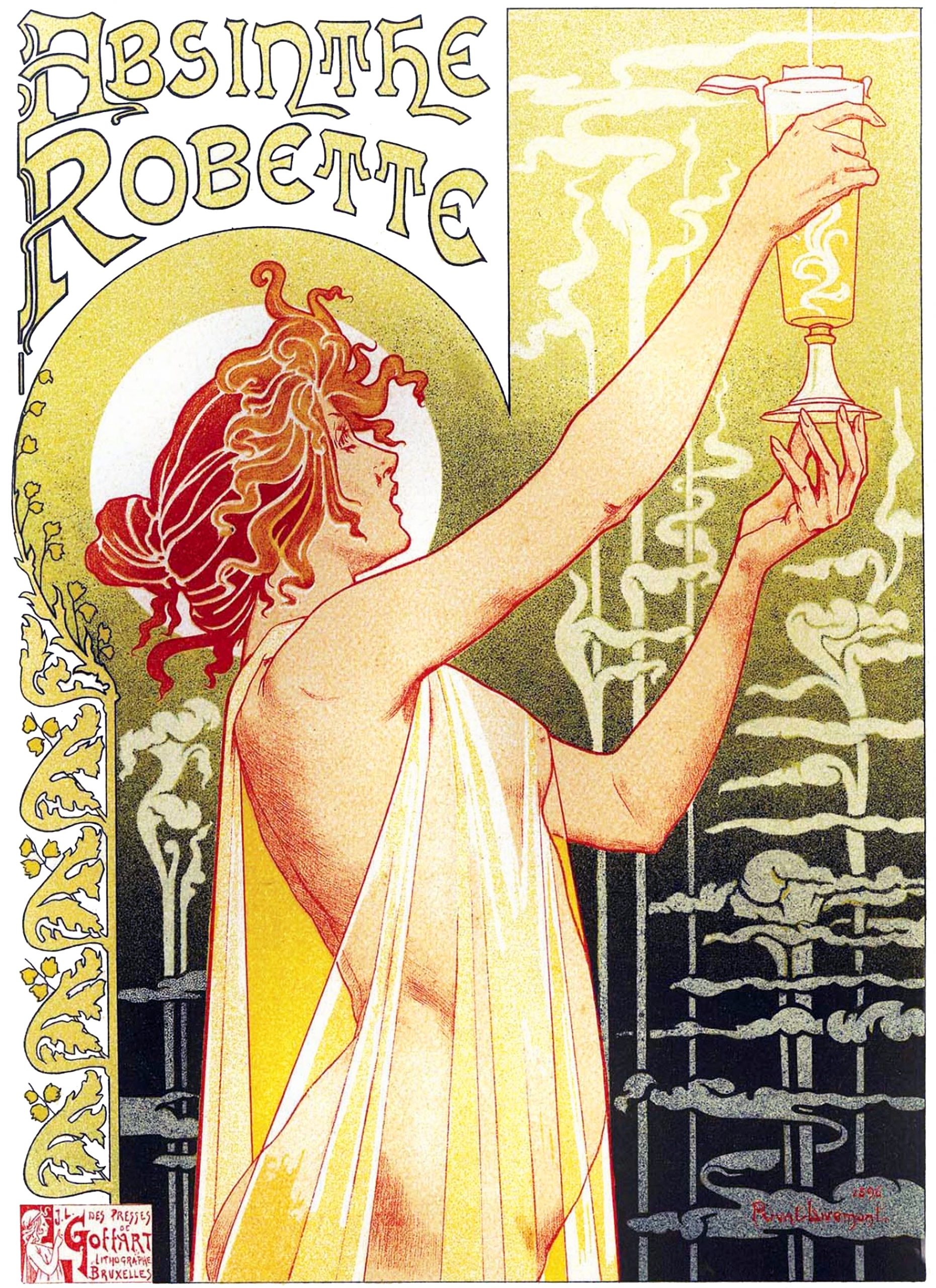

Known as ‘the green fairy’ to its adherents and ‘the wicked green witch’ to its detractors, absinthe was not for the faint-hearted. ‘After the first glass’ Oscar Wilde wrote, ‘you see things as you wish they were. After the second, you see things as they are not. Finally, you see things as they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world’. Degas’ drinkers portrayed in L’Absinthe (1876), one of around 130 canvases featuring the drink produced by artists such as Manet, van Gogh, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Picasso, stare vacantly and glumly into the distance.

Associated with fits, convulsions, hallucinations, insanity, and even death, absinthe drinkers were popularly described in Paris as ‘buying a one-way ticket to Charenton’ — the name of the local lunatic asylum. By the early 20th century around 30 per cent of the adult male population of large swathes of France had been hospitalised with what was known as absinthisme.

In the 1870s the influential French psychiatrist Valentin Magnan studied the effects of thujone, a neurotoxin found in wormwood which is hallucinogenic in large quantities and lethal in larger quantities still, by force-feeding pure wormwood oil extract to laboratory animals. He discovered that they went into violent convulsions before dying. This convinced him of the deleterious effects of wormwood on the human body, effects which, he believed, could be passed on to the unborn descendants of absinthe addicts.

By the early 20th century, an unlikely alliance of the emerging temperance movement and winegrowers desperate to regain their market share after the phylloxera disaster seized on Magnan’s findings to pressurise the authorities to rid society of absinthe’s menace. Their cause was helped in 1905 by an allegedly absinthe-addled Swiss farmer, Jean Lanfray, murdering his heavily pregnant wife and two daughters, an outrage that shocked Europe.

The Belgians banned absinthe in 1905, and soon other countries followed suit. The Swiss, after a referendum held on July 5, 1908, specifically wrote absinthe’s prohibition into their constitution, a move that drove production underground. It was banned in America in 1912 and in France by Presidential decree on March 16, 1915, where pastis quickly took its place. The Italians banned it after a referendum in 1932.

Magnan’s research has now been discredited, his methods likened to trying to establish the effect of drinking coffee by feeding animals with pure caffeine, and the levels of thujone were unlikely to have been dangerous. More harmful were the inferior and often poisonous ingredients which unscrupulous distillers used to cash in on the demand for a cheap absinthe, such as copper sulphate for colouring and antimony trichloride to produce the clouding effect. In effect, absinthe had become a victim of its own success.

The ban on absinthe was not universal, though. It could be made and consumed legally in Spain, Pernod distilling it in Tarragona until the 1960s, and in what is now the Czech Republic, where the local version had lost it’s ‘e’ and was known as absinth.

Never a popular drink in Britain, absinthe was not banned outright but, as it had to be imported, supplies had dried up. Nevertheless, drinks entrepreneur George Rowley saw an opportunity to bring the Czech absinth into the UK, exploiting the definition of what was an acceptable level of thujone in the EU Council Directive 88/388/EEC.

In the summer of 1998, working with his local Trading Standards Officer, Paul Passi, Rowley demonstrated that the amount of thujone in absinth was well within the limits defined by the EU. His Czech drink was launched with some style in the appropriately louche setting of the Groucho Club in November 1998.

Gradually, the green fairy got the green light and other countries began to legalise the drink, and even the French formally lifted their ban in 2011 after pressure from the Fédération Française des Spriteux. For aficionados, though, the new wave of Bohemian-style absinthes which emerged in the 1990s were inferior substitutes. To recreate the true essence of the 19th century spirit, the French Absinthe Museum collaborated with Rowley and Marie-Claude Delahaye to create La Fée Absinthe in 2000, the first real absinthe to be distilled commercially in France since the ban.

Those now enjoying a taste of la vie bohème owe a lot to George Rowley.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.