Curious Questions: Why is pancake day called 'Shrove Tuesday'?

Martin Fone investigates how Shrove Tuesday got its name — and also unveils the history of the day that precedes it, Collop Monday.

I’m writing this piece on what is known as National Lame Duck Day, I will leave you to ponder the irony, a tag symptomatic of the modern trend of allocating a name to each day of the year. Some bear the hallmarks of a desperate PR department trying to drum up interest in something they are promoting, names destined to be as transient as the product or cause themselves. Others, though, have the weight of history or religious observance behind them.

Take Shrove Tuesday. This marks the end of Shrovetide, when Christians make their preparations ahead of the period of abstinence that is Lent. It always seems to catch me unawares, a fate shared by any day in the religious calendar that takes as its lodestone that moveable feast, Easter. Shrovetide’s relativity to Easter is fixed, starting on Septuagesima Sunday, the seventh Sunday before Easter, and ending, seventeen days later, on the Tuesday following Quinquagesima Sunday. As Easter is the first Sunday after the first full moon following the vernal equinox, Shrove Tuesday, falling 47 days before, can be anytime between February 3rd and March 9th.

It’s all as clear as mud. No wonder we get taken by surprise.

"Our admiration of our mother’s prowess lasted only as long as it took her to produce the first two pancakes"

The name of Shrove Tuesday is derived from the verb ‘to shrive’, meaning ‘to obtain absolution by way of confession and penance’. The means of this ‘shriving’ is, of course, making pancakes.

As children, my brother and I would congregate in the kitchen to watch our mother gather the key ingredients: eggs, symbolising creation; flour, the staff of life; salt, representing wholesomeness; and milk, purity. After pouring the mix into a frying pan, she would twist it from side to side to ensure that the gloop had filled the bottom and then, standing with her feet spread wide, grasp the handle firmly in one hand, manipulating the pancake to ensure it hadn’t stuck. When satisfied it had cooked, with one flick of the wrist, she would propel the pancake into the air and adroitly catch it once more.

In truth, our admiration of our mother’s prowess lasted only as long as it took her to produce the first two pancakes, her dexterity being insufficient to challenge Brad Jolly’s feat of tossing a pancake 140 times in just a minute without deviation, hesitation but with plenty of repetition in Sydney in 2012, and the ceiling space cramping any thoughts of emulating Dominic Cuzzacrea who, in 2010 in New York, managed to toss his an astonishing 9.47 metres into the air. We were rather too preoccupied in consuming the fruit of her labours whilst they were still warm.

During Lent, Christians were supposed to eschew eggs and dairy products and pancakes were an appetising way of using up the leftovers. Meat was also firmly off limits, but fish were in a different kettle altogether. In his first letter to the Corinthians, St Paul helpfully categorised flesh into four types (15:39), distinguishing the flesh of beasts from that of fish. In the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas, writing in his influential Summa Theologica, argued that as animals were more like man in body, they gave greater pleasure as food and were, therefore, inimical to the purpose of fasting, namely ‘to bridle concupiscences of the flesh’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

As fish were from a lower order, what we would call a pescatarian diet was perfectly acceptable for the observers of Lent. What constituted a fish, though, became a question open to some interpretation — at least in the religious, if not scientific community. The Bishop of Quebec decreed in the 17th century that beavers qualified and, as recently as 2010, the Bishop of New Orleans advising his flock that ‘alligator is considered in the fish family’.

Despite this clerical sophistry, it was quite clear that over Lent the flesh of animals such as pigs and cows was not to pass the lips of God-fearing Christian folk. This left them with a bit of a problem, in the days before refrigeration: what to do with any meat they had left over before the forty days of fasting? Traditionally, meat was cut up into strips, making the carcass easier to handle, to preserve by salting and to hang up. These strips of meat — what we would term steaks — were known in northern England, from at least Tudor times, as collops, a word derived from the Norse word meaning a slice of meat.

The Nottingham Evening Post, in its edition of March 1, 1926, provided some insight into the practice: ‘Collop Monday, the day before Shrove Tuesday, is so-called because our ancestors cut their fresh meat into collops or steaks for salting or hanging up till Lent was over.’ The suspicion that this might have been a tradition that had lapsed into obscurity, even by the late 19th century, is heightened by words in a piece in the York Herald of February 29, 1896: ‘Collop Monday is the day before Shrove Tuesday. It has little or no significance now.’

"I will celebrate Collop Monday with a large plate of bacon and eggs. After all, there are some traditions worth reviving"

With the prospect of prolonged abstinence from meat, it is not surprising that Collop Monday was celebrated with a meal of some sort. Daniel Defoe in his Tour of Great Britain (1726) recorded that in the North it was so called because of, ‘an immemorial custom there of dining that Day on Eggs and Collops.’ John Brand, a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, noted in 1849 that ‘eggs and collops compose a usual dish at dinner on this day’ while the York Herald put some more flesh on the bone by reporting that ‘it was customary…to have a dish of collops of bacon, with eggs, on this day.’

It is fascinating to note that often the last flavour of meat they would have savoured before the long fast of Lent was bacon, a meat I would miss profoundly if I ever became a vegetarian. The fat that oozed out of the sizzling meat was used to flavour the pancakes cooked the following day.

The York Herald, my go-to authority on matters Collop-related, also noted that ‘children in these counties [Yorkshire, Lancashire and Durham] used to go from door to door singing.’

Rather like the Hallowe’en, there was an implied threat in the song, as this example shows:

Once, twice, thrice

I give thee warning

Please to make some pancakes

‘Gin tomorrow morning

In Cornwall, the day is known as Peasen Monday, because pea soup is consumed along with salt bacon. In the west of the county, the evening has a special name as well: Nickanan Night, the time for the local youths to play tricks on their neighbours and to extort the promise of a pancake the next day.

This year, 0n February 24th, I will celebrate Collop Monday with a large plate of bacon and eggs. After all, there are some traditions worth reviving.

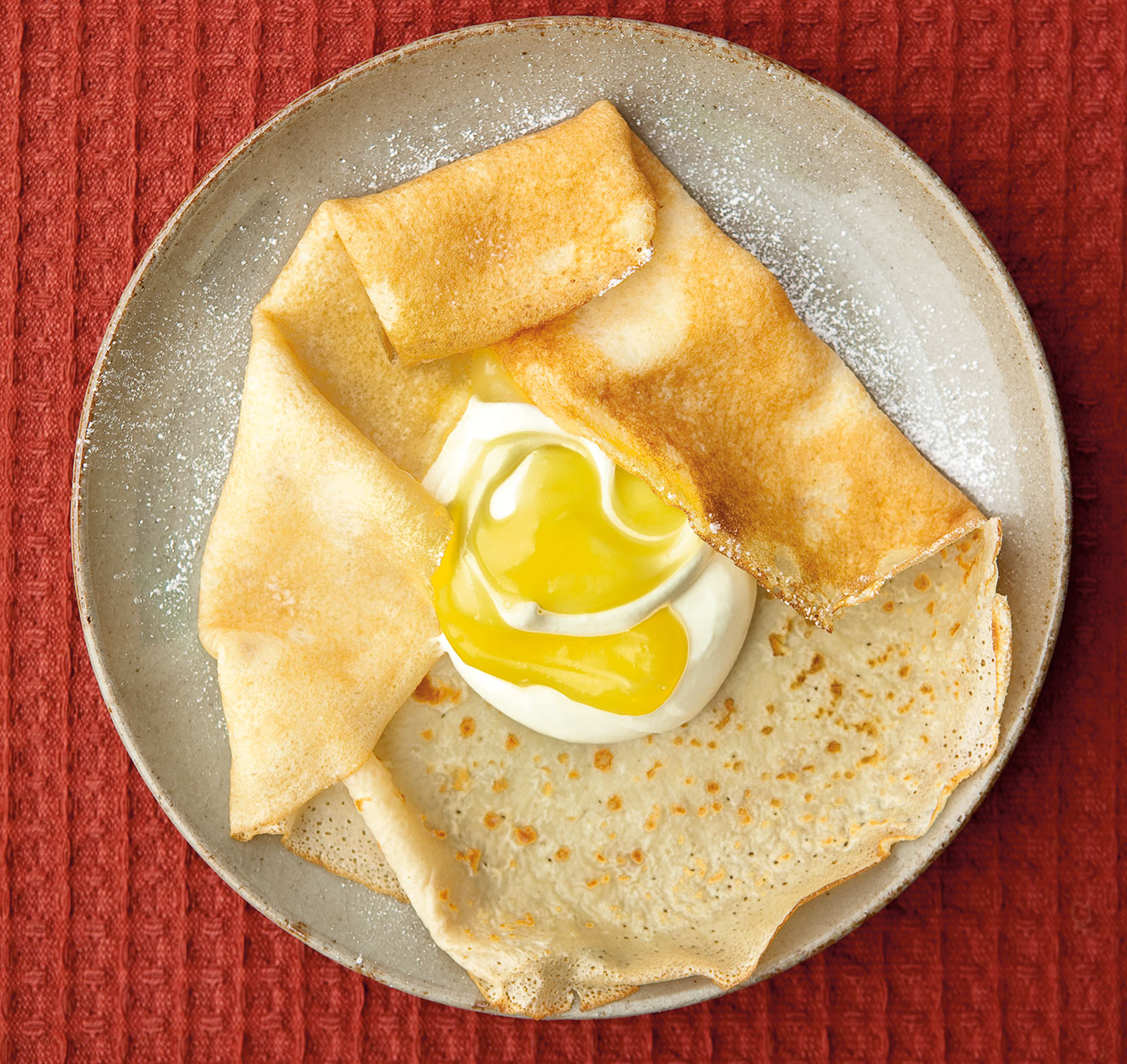

Eight perfect pancake recipes for Shrove Tuesday

Enjoy our foolproof pancake recipe - and eight enticing ways to make them better than ever.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.