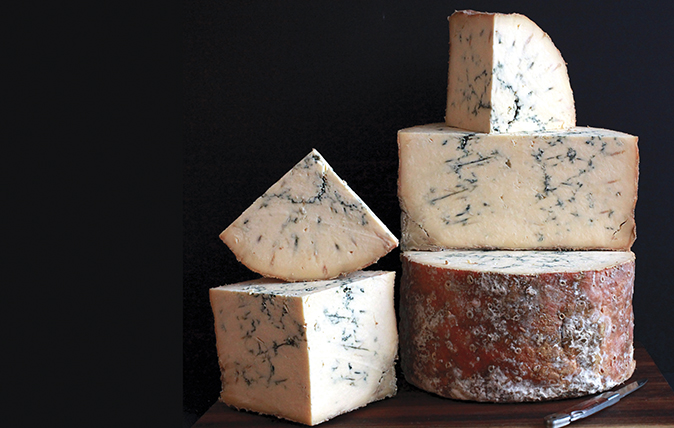

Curious Questions: Why doesn't Stilton cheese come from Stilton?

Britain's most famous blue cheese takes its name from a picturesque Cambridgeshire village — yet it's made nowhere near the place, and not even in the same county. Martin Fone investigates this strange culinary anomaly.

There are over 700 named British cheeses produced in the United Kingdom. In 2020 sales increased by 15% in volume and seventeen percent in value, with Cheddar — the nation’s favourite — accounting for just under half of all cheese sales.

For Stilton, though, times have been tough. Sales dropped by 30% in the same year, with the loss of the all-important hospitality sector and the reduction in the number of dinner parties due to the pandemic hitting it hard. A temporary blip, perhaps, as this most social of cheeses makes the perfect finale to a dinner party, its blue-veined creaminess the ideal accompaniment to a glass of port.

Stilton is one of 255 cheese-based products protected under European Union law by its Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) legislation, a status achieved in 1996, which post Brexit was replaced by the far from catchy 'Designated Origin UK Protected' or GI, Geographical Interest mark.

It comes in two forms, the familiar blue and the white which does not have the blue mould added and is less mature. White Stilton may be a rarity today, with five dairies making it and one under licence, but it was not always so. Brian Flynn’s 1932 murder mystery The Padded Door partly turns on a judge’s predilection for the blue-veined variety over the white, the latter being the standard restaurant fare at the time.

Even more of a mystery than Flynn's book, however, is that of Stilton's name. The village of Stilton — 70 miles north of London as the crow flies, and strategically positioned alongside the Great North Road — is exactly the sort of ancient, picturesque place you'd expect cheese to be made. Yet it isn't made there; and what's more, it actually can't be made there.

For a cheese to bear the name 'Stilton' it must be made in one of three counties, Derbyshire, Leicestershire, and Nottinghamshire, from locally-produced pasteurised milk. Currently, there are only six dairies licensed to manufacture the cheese, centred around the Vale of Belvoir, producing around a million full Stilton cheeses a year. The village of Stilton may have moved administratively from Huntingdonshire to Cambridgeshire in the 1970s, but it has never been in one of the three counties named in the PDO.

So why does the cheese bear its name if it cannot be made there?

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Frances Pawlett (or Paulet) from Wymondham near Melton Mowbray produced a cheese in the early 1740s which boasted several innovations; she changed the way the curd was crumbled to produce a more open texture, introduced ceramic pipes with holes in them so that the unpressed cheese could drain and mature, pierced it with stainless steel needles to allow the mould to develop, standardised its weight and size to a sixteen pound drum, and extended the cheese-making season from beyond its traditional summer months.

A relative of Pawlett’s, Cooper Thornhill, was proprietor of the Bell Hotel in Stilton in the 1740s, a popular staging post for travellers journeying between London and the north. She supplied the inn with her cheese, and it was so well received that Thornhill was soon operating as a small-scale wholesaler, selling it at half a crown a pound. Other coaching inns followed suit and the fame of the cheese soon spread far and wide. Not having a name, it was referred to as that cheese from Stilton.

Alternatively, Elizabeth Orton from Little Dalby, near Melton Mowbray, may have been the first to make the cheese, using a secret family recipe. It was known as Quenby, but her activities are not documented before 1730. Perhaps, more fancifully, credit is given to its creation to a Mrs Stilton, head dairymaid to the 5th Duchess of Rutland at Belvoir, although there is no documentary evidence to support this.

Stilton itself was a centre of cheese manufacturing. Daniel Defoe on his travels was less than complimentary about its wares in A tour thro’ the whole island of Great Britain (1725). “It is”, he wrote, “a town famous for cheese, which is call’d our English Parmesan, and is brought to the table with the mites, or maggots round it, so thick, that they bring a spoon with them for you to eat the mites with, as you do the cheese”.

It was clearly not a plain cheese that was served to Defoe, a self-avowed Cheddar man. His reference to Parmesan is ambiguous; it could be taken literally to refer to a hard, pressed cheese or figuratively to suggest its pre-eminence as a cheese, just as Parmesan was the acknowledged King of Cheeses.

Richard Bradley in 1726's A general treatise of husbandry and gardening published a receipt (recipe), for a cream cheese which he said was the “famous” Stilton cheese. “At the Sign of the Bell”, he wrote, “is much the best Cheese in Town the man of that House keeping strictly to the old Receipt. While others thereabouts seem to leave out a great part of the Cream which is the chief ingredient but for all this the Name this sort of Cheeses has got above others makes it sell for 12d per Pound upon the Spot”.

The cheese was pressed implying that it was hard. Bradley, though, was at pains to refute this in 1732, in The Gentleman and Farmer’s Guide for the Increase and Improvement of Cattle, when he described the cheese as so soft “one may spread it upon Bread like Butter”. Clearly, Bradley infers that John Brownell, the then proprietor of the Bell, was following an old recipe, a point reiterated in the testimony of John Pitts, one of Brownell’s successors, in William Marshall’s A General View of the Agriculture of the County of Huntingdonshire (1811).

Pitts asserted that Stilton was originally made in the village, basing his claim on the reminiscences of Croxton Bray, who, as a boy, was sent out with his three sisters and two brothers to collect cream in the neighbouring villages “for the purpose of making what is called Stilton cheese”. Parish records show that Bray was baptised in 1714 suggesting that this cream-based cheese must have been made in the early 1700s, well before Frances Pawlett and Mrs Orton started making theirs in Leicestershire.

Indeed, Leicestershire’s claim to be the home of Stilton was not asserted with any vigour until the close of the 18th century. William Marshall in The Rural Economy of the Midland Counties (1790) announced that “Leicestershire is, at present, celebrated for its “cream cheese” – known by the name of Stilton Cheese”.

Accounts from the early 19th century suggest that cheese was still produced in Stilton, but that the farmers were slapdash, resulting in “so many faulty and unsound cheeses”. Even in the early 1830s when William Cobbett was compiling his A Geographical Dictionary of England and Wales (1832) Stilton was still manufacturing cheese. He observed that Leicestershire’s cheese “so much resembles in quality that which is made at Stilton… that it is also called Stilton Cheese”.

As the quantity and quality of cheese produced in Stilton waned, the superior dairies in the Vale of Belvoir were quick to fill the vacuum and feed the demand for the tasty cheese. What we know today as Stilton is almost certainly the version developed by Frances Pawlett. To clarify the point, in the 1930s it was suggested that it should be renamed Meltonian Cream Cheese, but the name never caught on, leaving the pickle we have today.

Whether the village of Stilton was the first to make the type of cheese which bears its name may never be settled conclusively. What is clear, though, is that any attempt to revive Bradley’s recipe in the village will have to go by any name but Stilton.

Stilton: A grand part of our culinary heritage

Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without a plate of pungent Stilton. Nick Hammond visits the Colston Bassett Dairy to discover the

‘Tempt you with a glass of Sussex?’ English bubbly wins protected name status

Sussex sparkling wines have cemented protected name status, putting themselves up there with champagne, Cornish clotted cream... and of course

Celebrating toast: The best ways to eat toast

Leslie Geddes-Brown quizzes foodies for their ultimate ways to eat that most British of snacks: toast

The 12 essential cupboard ingredients that will let you cook (almost) anything

Lesley Geddes-Brown provides her list of kitchen essentials – keep all these to hand and you’ll be able to cook anything.

Credit: Cornish Pasty Association/Kate Whitaker

The bakers who saved the Cornish pasty

Proper Cornish pasties were in danger of dying out, but, thanks to a dedicated band of bakers, all that’s changed.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to last

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to lastKitchen and joinery specialist Artichoke had several clever tricks to deal with the fact that natural wood expands and contracts.

By Amelia Thorpe

-

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025Friday's quiz is an Easter special.

By James Fisher

-

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?As April 1 looms, Martin Fone tells the tale of one of the finest stunts ever pulled off.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade when there are more than 400 other varieties available worldwide? And do they really make the best preserve? Jane Wheatley investigates.

By Jane Wheatley

-

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this day

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this dayOnce packed with meat, such as ox tongue and mutton, alongside dried and candied fruit and extravagant spices, the mince pie is not what it once was — and food historian Neil Buttery says that's made them worse.

By Neil Buttery

-

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?Margarine has been a staple of our breakfast tables for over a century, but it hasn't always had a smooth ride — particularly from the dairy industry, who managed to impose a most bizarre sanction on their easily-spreadable, industrially mass-produced rival. Martin Fone explains.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?With the UK wine industry booming, Martin Fone takes a look at its history.

By Martin Fone

-

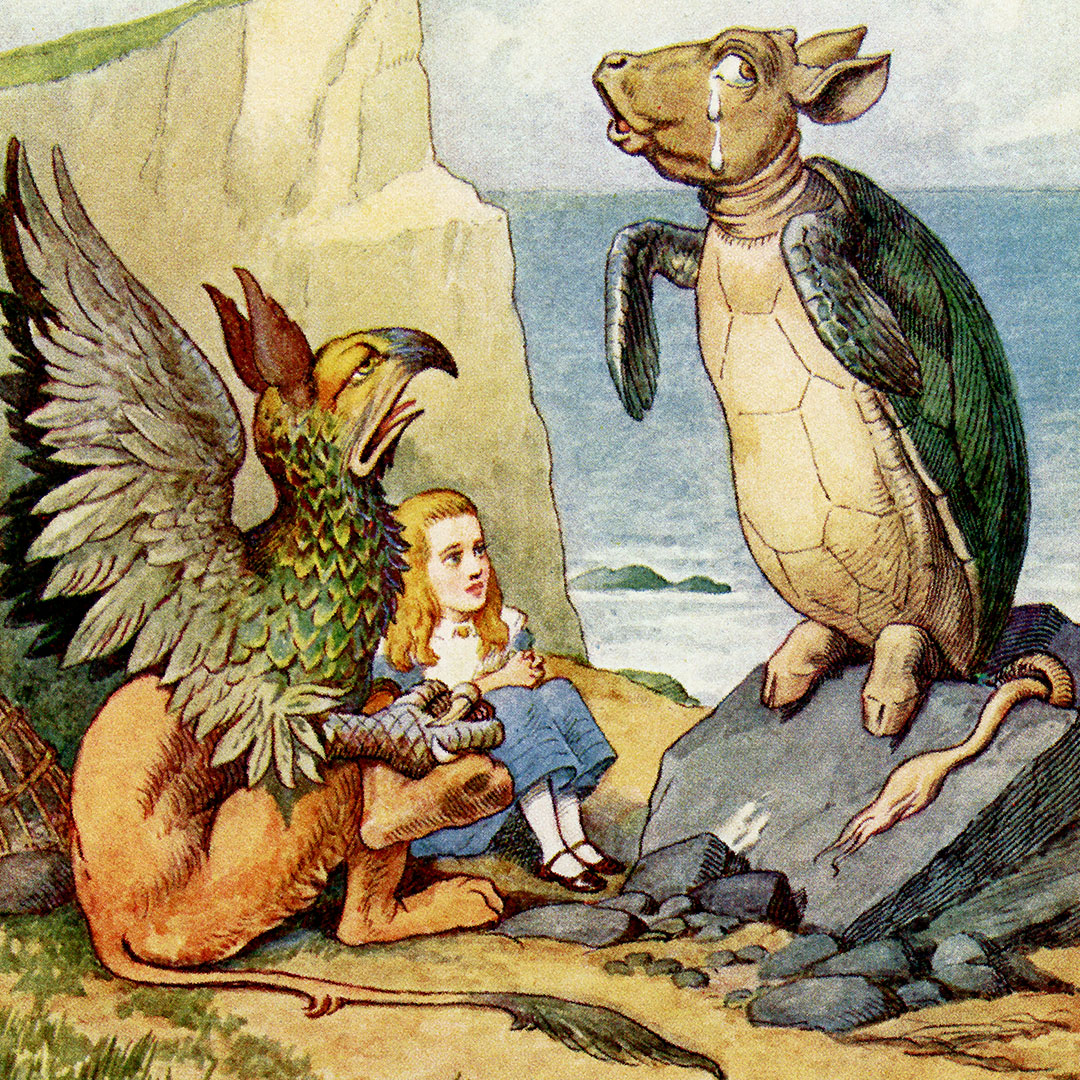

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?Martin Fone delves into the curious tale of an iconic Victorian delicacy: mock turtle soup.

By Martin Fone

-

A game of two halves — how the sandwich went from humble fare to a country-wide lunchtime obsession

A game of two halves — how the sandwich went from humble fare to a country-wide lunchtime obsessionWhat started life as a way to eat and play cards at the same time (so the story goes) is now the lunch of choice for the working world.

By Emma Hughes

-

Where to find the world's best club sandwich — and the story of this triple-layered paean to poolside delight

Where to find the world's best club sandwich — and the story of this triple-layered paean to poolside delightThe club sandwich, arguably the most famous of all sarnies, is a poolside staple, but its origins are tricky to trace, says Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker-Bowles