Curious Questions: Why do Polo mints have a hole in the middle?

Polos are famous as the mints with the hole — and have been since they were launched 75 years ago. But why did they get a hole in the first place? Martin Fone finds out.

Peppermint (Mentha x piperita), an indigenous natural hybrid of water mint and spearmint, was first cultivated here in the late seventeenth century. Britain’s epicentre of peppermint cultivation was Mitcham and its environs, nestling in the Wandle’s sleepy headwaters, it provided perfect conditions for the plant to flourish.

Of the 250 acres cultivated by physic gardeners in Mitcham, freeholders who grew medicinal plants, such as lavender, wormwood, camomile, aniseed, rhubarb, and liquorice, more than one hundred were given over to peppermint, according to David Lyson’s The Environs of London vol 1 – County of Surrey (1792). ‘Forty years since, ‘he observed, ‘a few acres only were employed in the cultivation of medicinal herbs in this parish. Perhaps there is no place where it is now so extensive’.

Peppermint was harvested during July and August with yields of around four to six tons of oil per acre. The plant’s size was no indicator of how much oil it would produce. ‘When the summer has proved wet and cold’, a writer in the Canadian Pharmaceutical Journal, Volume IX (1875-6) noted, ‘the plants, although bulky, have been known to produce only a small proportion of oil, and in other years, when the season has been warm and dry, the reverse has been the case, and small plants have yielded a double quantity of oil’. The aroma of peppermint was a distinctive feature of Mitcham’s lanes.

In Lyson’s day the peppermint was sold fresh to be distilled into oil elsewhere but by the early 19th century Mitcham and Wallington had their own stills, smoke from their chimneys billowing into the sky during the harvest season. Even the celebrated Bond Street perfumer, Messrs. Piesse and Lubin, had a distillery on the high road to Mitcham.

As well as for its scent, peppermint was valued for its medicinal properties, the Egyptians using it as a digestive aid and a cure for stomach pains caused by flatulence. By the 18th century it had become a panacea for a wide range of ailments from nausea, vomiting, respiratory infections, and menstrual disorders to cholera, diarrhoea, and laryngitis. It made its first appearance in Sir Hans Sloane’s London Pharmacopoiea in 1721, the definitive list of drugs that English chemists were authorised to sell.

From mediaeval times peppermint was also used as an anaesthetic for toothache and as a mouth freshener, either chewed raw or mixed with vinegar and taken as a mouthwash. The wide availability of sugar in the 18th century led to a dramatic rise in dental decay, fuelling a demand for breath fresheners. Mitcham peppermint made hay, Lysons noting that ‘it being much used in making a cordial well-known to the dram-drinkers’.

Initially, these early mouth fresheners were taken in liquid form, making them inconvenient for maintaining fresh breath when out and about. In 1780 a confectioner based in Fell Street in the City of London, William Smith, hit upon the idea of making lozenges from sugar, gum arabic, oil of peppermint, gelatin, and glucose syrup.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

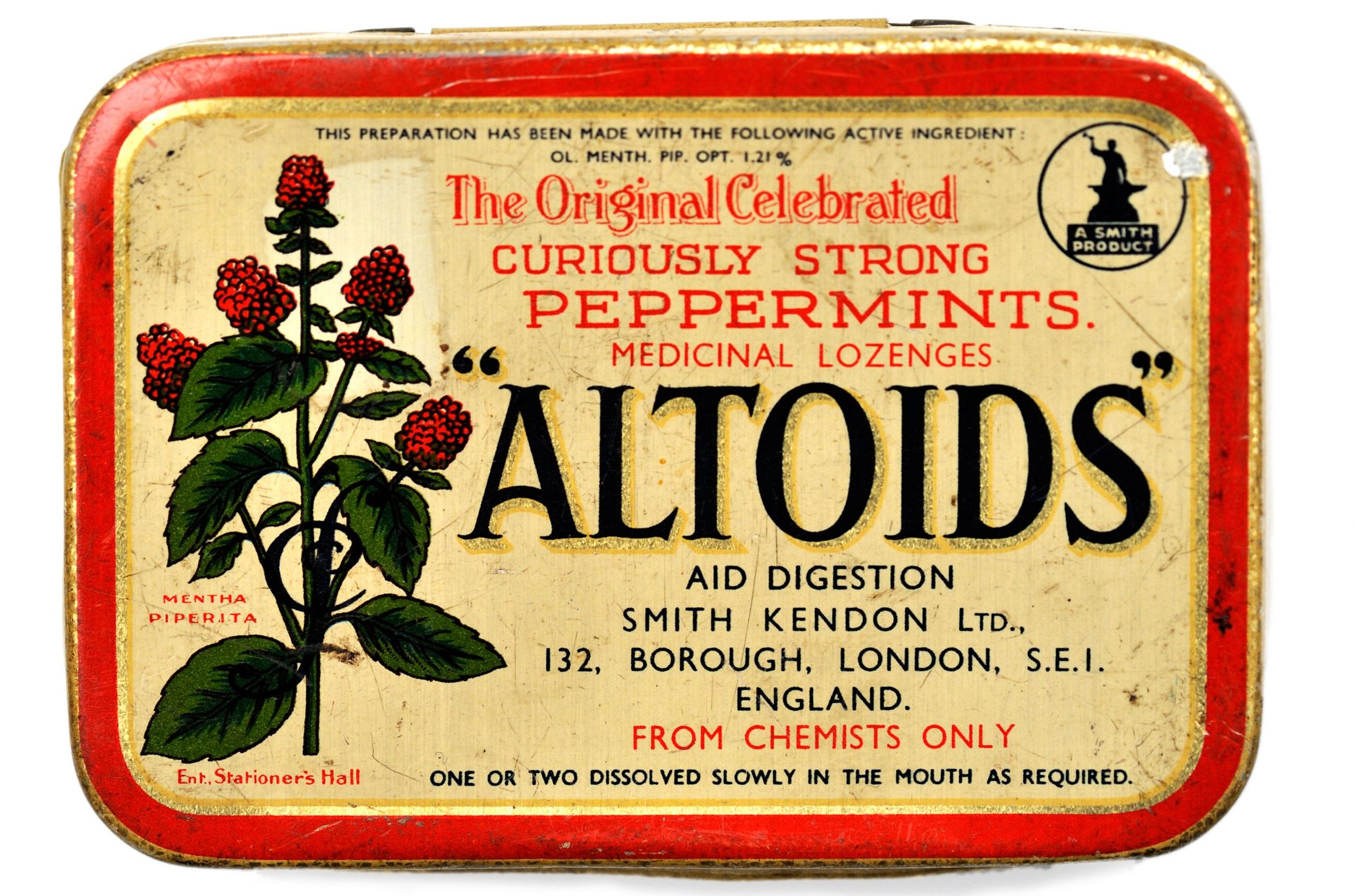

Called Altoids and marketed as a ‘stomach calmative to relieve intestinal discomfort’, they were considerably stronger than other mint products around at the time, thanks to the generous quantity of real peppermint oil called for in the recipe.

Portable and convenient to take, these 'curiously strong mints' soon became popular both for their medicinal properties and as a piece of confectionary to maintain fresh breath. Altoids, still using the original recipe, remain one of our leading mints.

Altoids were not sold in the United States until the twentieth century, by which time the Americans had their own curious mint, courtesy of an Ohioan chocolatier, Clarence Crane. Searching for an alternative to chocolate which would withstand the summer heat, he hit upon the idea of producing mints in 1912.

Crane’s mints were white in colour, round and peppermint flavoured, made using the same type of machine with which pharmacists produced their round, flat pills. To ensure that his mints stood out from the competition, he stamped a hole into the middle of each one. As their annular shape reminded him of life belts, Crane called his mints Life Savers, a name that was not without its irony as they were introduced in the year that the Titanic sank. They were advertised with the strap line of ‘For That Stormy Breath’.

Crane sold his business to E J Noble the following year. A consummate salesman, Noble soon established Pep-O-Mint, the original version of Life Savers, as a household name, partly through the morally dubious method of recruiting youngsters to sell them on commission. Marketing them as ‘The Candy Mint with the Hole’, he replaced the original cardboard containers which got soggy with tin-foil wrappers to keep the mints fresh.

Life Savers were introduced to Britain in 1916 and manufactured here from 1923, reaching the peak of their popularity in 1931 when sales topped 2.28 million packets. During the Second World War Rowntree’s manufactured Life Savers under licence but the war and rationing saw sales dwindle to almost nothing by 1947.

For Rowntree’s, the 1930s were its golden age, the decade in which the marketing genius of George Harris came to the fore, launching such best-sellers as KitKat, Smarties, Aero, Black Magic, and Dairy Box. He intended to create a mint akin to the Life Saver in 1939, but the advent of war put paid to those ambitions. However, in 1948, judging the conditions to be right he launched what he called Polos, a name, derived from Polar to denote the mints’ cool freshness.

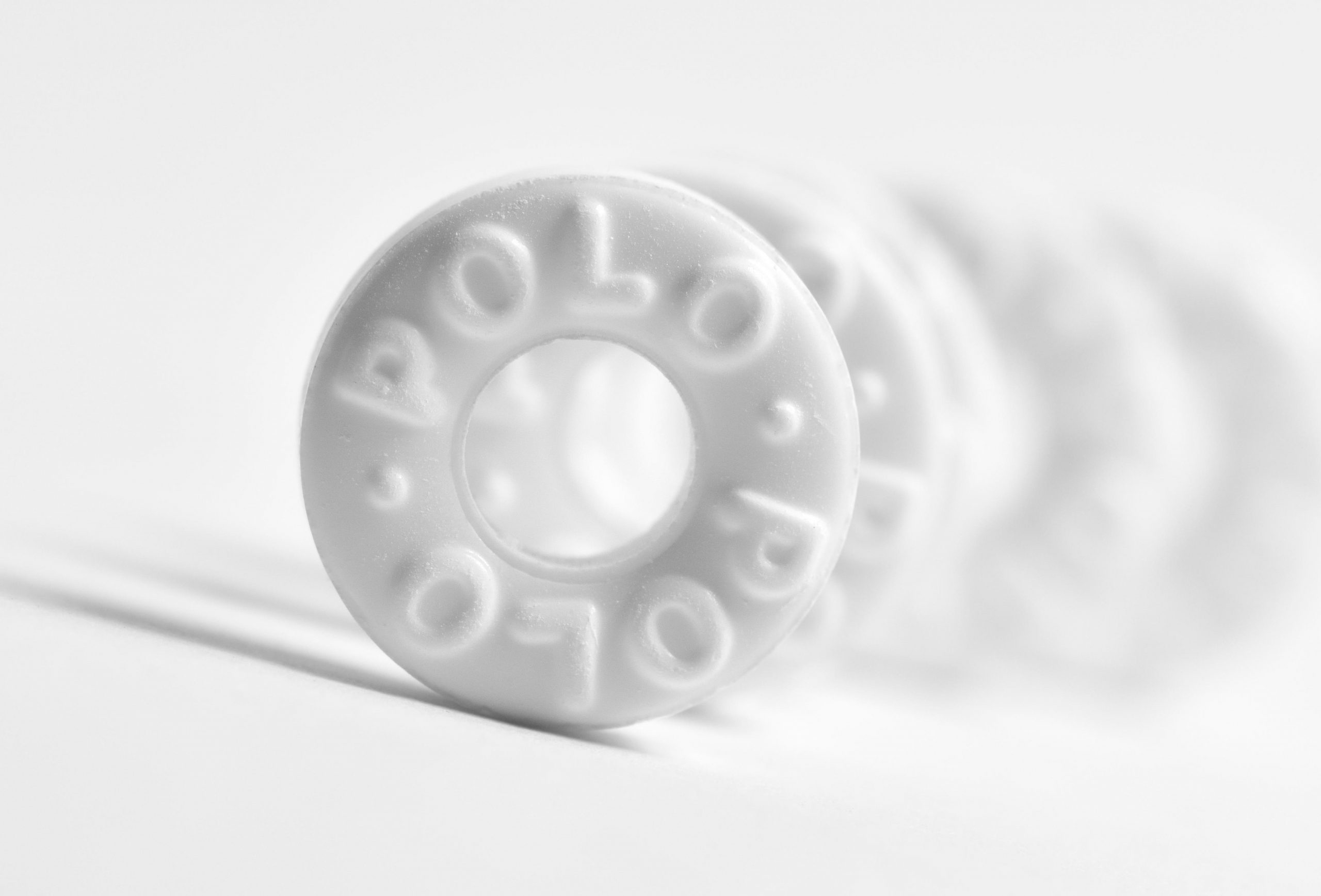

Peppermint flavoured, white in colour, round, approximately 1.9 centimetres in diameter and 0.4 centimetres thick, and with a trade mark 0.8-centimetre-wide hole, there were twenty-three in a packet, tightly wrapped in aluminium foil backed paper. They were even marketed as ‘The mint with the hole’, capitalising upon Life Savers’ failure to protect their annular shape with a patent. Nevertheless, Rowntree’s felt it necessary to protect their position further by clearly marking on the packaging that the mints were manufactured by them.

Unable to compete with the domestic brand strength of Rowntree’s, Life Savers were withdrawn from sale in the UK in 1956. Subsequent attempts to relaunch them have met with failure.

Now owned by Nestlé, the Polo plant in York can produce 22,000 sweets a minute or 1.37 million packs a day. For those who crunch rather than chew their Polos, it is worth remembering that each mint is put under 75 kilonewtons of pressure, the equivalent of the weight of two elephants jumping on it. And, yes, the mint is made with a hole already in it.

The hole was also responsible for an early outbreak of EU-scepticism. On April Fool’s Day, 1995, Nestlé Rowntree’s marketeers announced that ‘in accordance with EEC Council Regulations (EC) 631/95’ they would no longer be producing mints with holes. Cue national outrage.

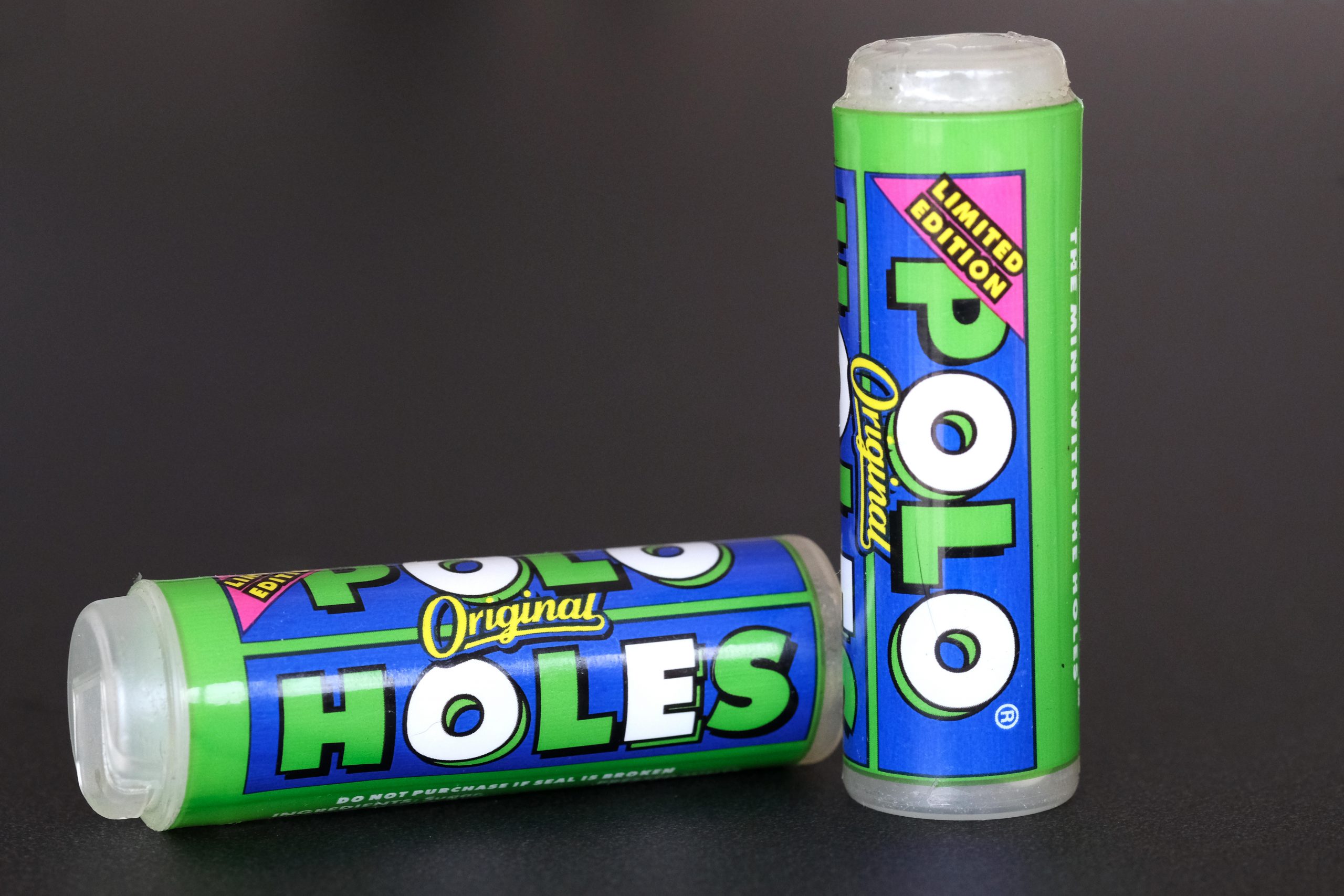

The following April 1st, inevitably, they suggested they were launching Polo Holes, described as ‘the hole with the mint’. And equally inevitably, the joyous response to the joke prompted the company to go ahead and manufacture the holes for real.

With its unusual shape backed by quirky advertising, Polos have found the recipe for suck-cess, maintaining their position as one of the country’s best-selling mints. Their diamond anniversary cannot pass unnoticed.

Curious Questions: Did mince pies really once contain meat?

Martin Fone investigates the most traditional seasonal food of all: mince pies.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.