Curious Questions: Who was Earl Grey — and why are we drinking his tea?

If you've ever stopped to wonder exactly which member of the aristocracy put his name to the floral, perfumed tea, Martin Fone has the answer.

There is something quintessentially English about a nice cup of Earl Grey tea, perhaps accompanied by a cucumber sandwich or a slice of Victoria sponge. Indeed, according to a survey conducted by Opinium Research, the results of which were published in The Telegraph on June 4, 2010, drinking Earl Grey was indicative of the fact that one is posh.

That may say more about the prejudices of the respondents than anything else, but there is no getting away from the fact that there is a certain cachet associated with a tea bearing that name.

Any tea flavoured with bergamot, an oil extracted from the rind of bergamot oranges, native to the Far East and widely grown in Italy, can be called an Earl Grey, as the name is not a registered trademark. It is usually drunk without milk or, if you must, with just a dash. There are variations on the theme as well: French Earl Grey contains rose petals as well as bergamot; Russian Earl Grey uses lemongrass; and if you want a citrus overload, try Lady Grey which boasts the addition of Seville oranges.

'The adulteration of foodstuffs with additives — some of which were positively harmful like arsenic, copper and black lead — was not uncommon'

The use of bergamot as a flavouring and scent had a bit of a bad reputation down the ages, particularly — but not exclusively — in relation to tea. In the 18th century bergamot was added to snuff to give it a distinctive aroma. In the early 19th century it was used to give a cheap and low-quality tea the veneer of something of superior quality which warranted a higher price. This practice was described in an article entitled 'To render Tea at 5s a Pound equal to Tea at 12s', published in The Lancaster Gazette on May 22, 1824: 'The flavouring substance found to agree best with the original flavour of tea, is the oil of bergamot, by the proper management of which you may produce from the cheapest teas the finest flavoured Bloom, Hyson, Gunpowder, and Cowslip.'

In the absence of any effective form of control, the adulteration of foodstuffs with additives — some of which were positively harmful like arsenic, copper and black lead — was not uncommon and tea, a relatively expensive product, would have been seen as fair game.

Occasionally, an unscrupulous trader would go too far and the authorities were stirred into action. The Bristol Mercury noted in its edition of May 13, 1837 that an injunction had been served on a London grocer preventing him from selling his tea. 'Brocksopp & Co’s Mowqua’s small-leaf gunpowder was so inferior a tea,' it lamented, 'that deponents could not set any price upon it… it was artificially scented and appeared to have been drugged with bergamot in this country.'

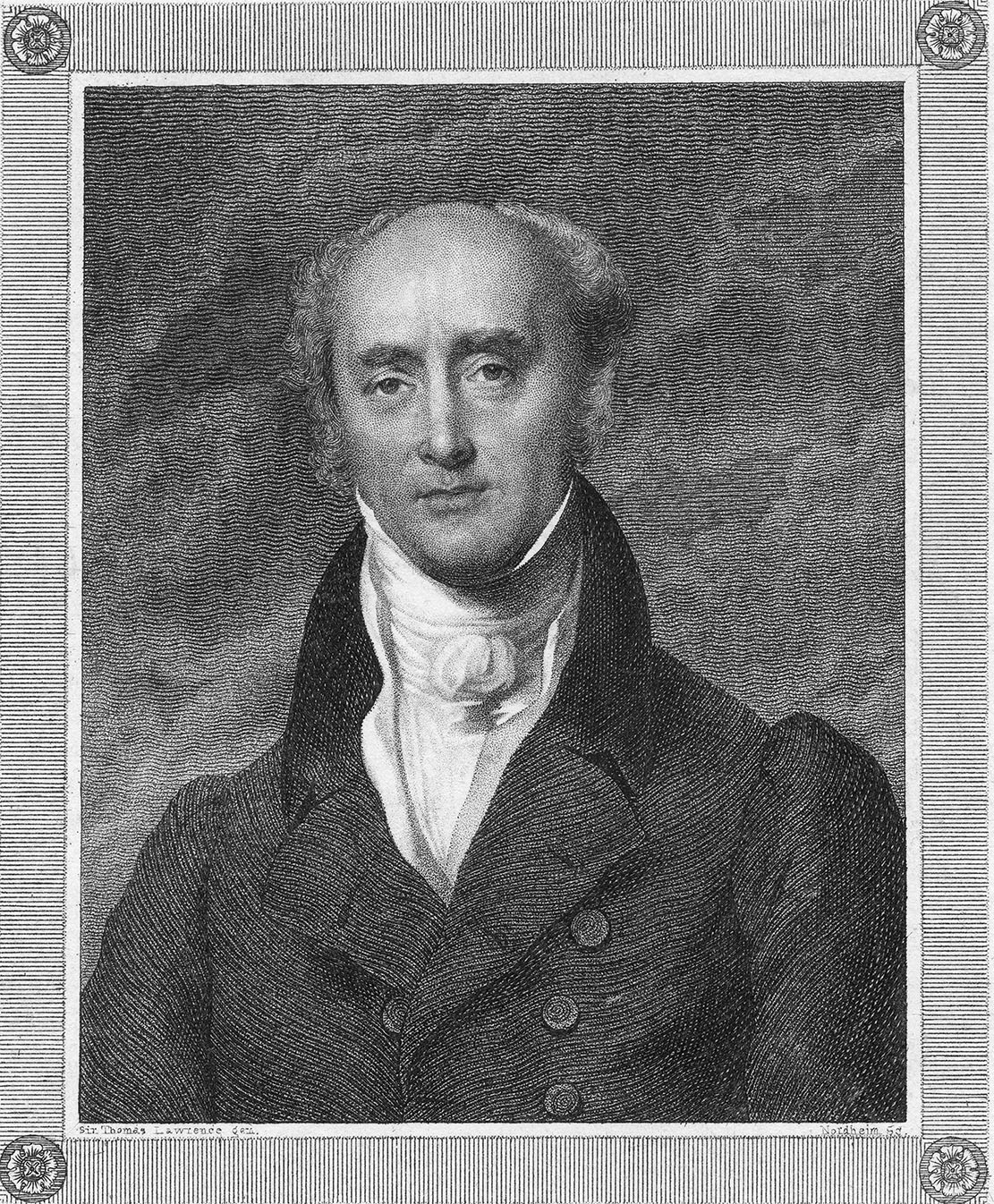

The member of the Grey family popularly associated with the tea is Charles, the second Earl, who served as Prime Minister from November 22, 1830 until July 9, 1834. Under his stewardship the Reform Act of 1832 and the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833 were passed. He also removed the monopoly of the East India Company on importing tea from China, thus lowering the price and enhancing the popularity of the beverage.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

We undoubtedly have a lot to thank him for, but did Charles Grey really have anything to do with the tea that seemingly bears his name?

The story that the then Lord Grey told to The Daily Telegraph in 1994 was that during Grey’s premiership he had sent an envoy to China who then saved the life of a mandarin’s son. The grateful mandarin shipped this special blend of tea, together with the recipe, to England. Grey was so delighted that he got his tea merchant — alas unnamed — to copy it.

An alternative version appears on the website for Howick Hall, Grey’s country manor. It claims that the tea was blended specially for his Lordship — by a Chinese mandarin, naturally — to hide the taste of lime in the water drawn from the local well, another interesting example of the use of bergamot to hide an unwanted taste.

The tale goes on to claim that Lady Grey used the blend when entertaining in London, thus sealing its popularity. This version of events seemed to have been confirmed by tea wholesalers Jacksons of Piccadilly — who are still going, albeit part of the Twinings family — in an advertisement dating from around 1928, in which they claimed to have introduced it at the Earl’s request in 1836.

'Twinings did obtain the endorsement of the sixth Earl Grey, Richard — it is his signature that appears on their packets'

Charming and convenient as these stories are, there are some troubling elements to them. During the 1830s China maintained a rigid trade and diplomatic embargo, shutting its borders to foreigners, tensions over which boiled over in 1839 into the First Opium War. Added to that, bergamot was not used as a flavouring for tea as it was not grown there.

What the Chinese did have, though, was Neroli oil derived from the blossom of the bitter orange tree, citrus aurentium. In correspondence recently unearthed in the archives of the East India Company their botanist, Sir George Staunton, reported to Sir Joseph Banks in 1793 that the Chinese scented their tea with it. Banks is said to have experimented with various flavourings before settling on the final recipe. Bergamot, more readily available in the West, is a subspecies of neroli and, intriguingly, Banks was a friend of Grey.

To stir the pot further, from at least 1852 William Grey & Co advertised extensively their Grey’s Tea, often with an accompanying rhyme which went as follows:

If your pockets and palates you both want to please, Buy William Grey’s finest of Teas His, at Four Shillings, is unequale’d they say, Then come with your money, and purchase of Grey.

Grey’s 'Red Canister Tea Warehouse' was based in Morpeth, only a few miles away from the Grey’s seat in Howick. And while Grey’s of Morpeth went out of business, their 'Celebrated Grey Mixture Tea' lived on, thanks to the efforts of Piccadilly-based blenders Charlton & Co.

In 1867, Charlton & Co were advertising the tea in the periodical John Bull in 1867 at a discounted price of 4s 6d a pound, down from 5s 6d. By 1884, in The Morning Post, they were promoting it as 'the celebrated tea, Earl Grey’s Mixture', the first known usage of the name. It may be that the addition of Earl was a bit of creative copywriting to give the tea an air of respectability and to distance it from the shady practice of product adulteration of half a century earlier.

Whilst Twinings did obtain the endorsement of the sixth Earl Grey, Richard — it is his signature that appears on their packets — I think we have to conclude that there is no certain connection linking the family with the invention of the tea. The use of bergamot, for purposes nefarious or otherwise, is well evidenced earlier and independently of them and, perhaps, the brand was established with the help of Grey’s of Morpeth and their celebrated tea.

Whatever the truth may be, one of our most prestigious teas has certainly had an interesting and murky history.

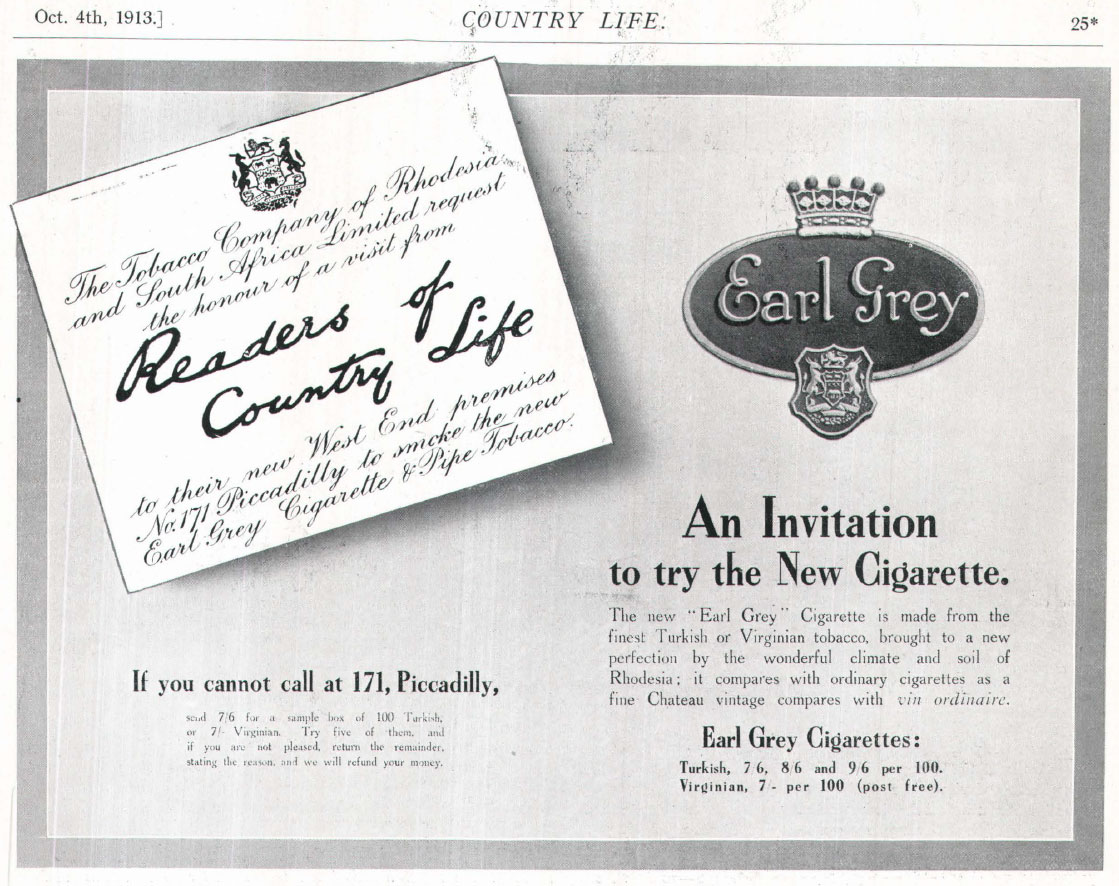

And as for the rather less well known Earl Grey cigarettes? That's another story entirely...

Credit: Alamy

Jason Goodwin: 'In a regimented, digital world, where everyone seems to be selling something, yeast and bacteria are free and wild'

Jason Goodwin discusses kombucha, the deceptively foreign-sounding tea-based drink, among other weird and wonderful things produced by home fermentation.

Hot cross bun bread and butter pudding

Easter is just around the corner, and if you find yourself with leftover hot-cross buns on your hands that have

Credit: Gill Kennett / Alamy Stock Photo

Grey seals: The doe-eyed ‘people of the sea’ who are full of surprises

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to last

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to lastKitchen and joinery specialist Artichoke had several clever tricks to deal with the fact that natural wood expands and contracts.

By Amelia Thorpe

-

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025Friday's quiz is an Easter special.

By James Fisher

-

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?As April 1 looms, Martin Fone tells the tale of one of the finest stunts ever pulled off.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade when there are more than 400 other varieties available worldwide? And do they really make the best preserve? Jane Wheatley investigates.

By Jane Wheatley

-

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this day

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this dayOnce packed with meat, such as ox tongue and mutton, alongside dried and candied fruit and extravagant spices, the mince pie is not what it once was — and food historian Neil Buttery says that's made them worse.

By Neil Buttery

-

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?Margarine has been a staple of our breakfast tables for over a century, but it hasn't always had a smooth ride — particularly from the dairy industry, who managed to impose a most bizarre sanction on their easily-spreadable, industrially mass-produced rival. Martin Fone explains.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?With the UK wine industry booming, Martin Fone takes a look at its history.

By Martin Fone

-

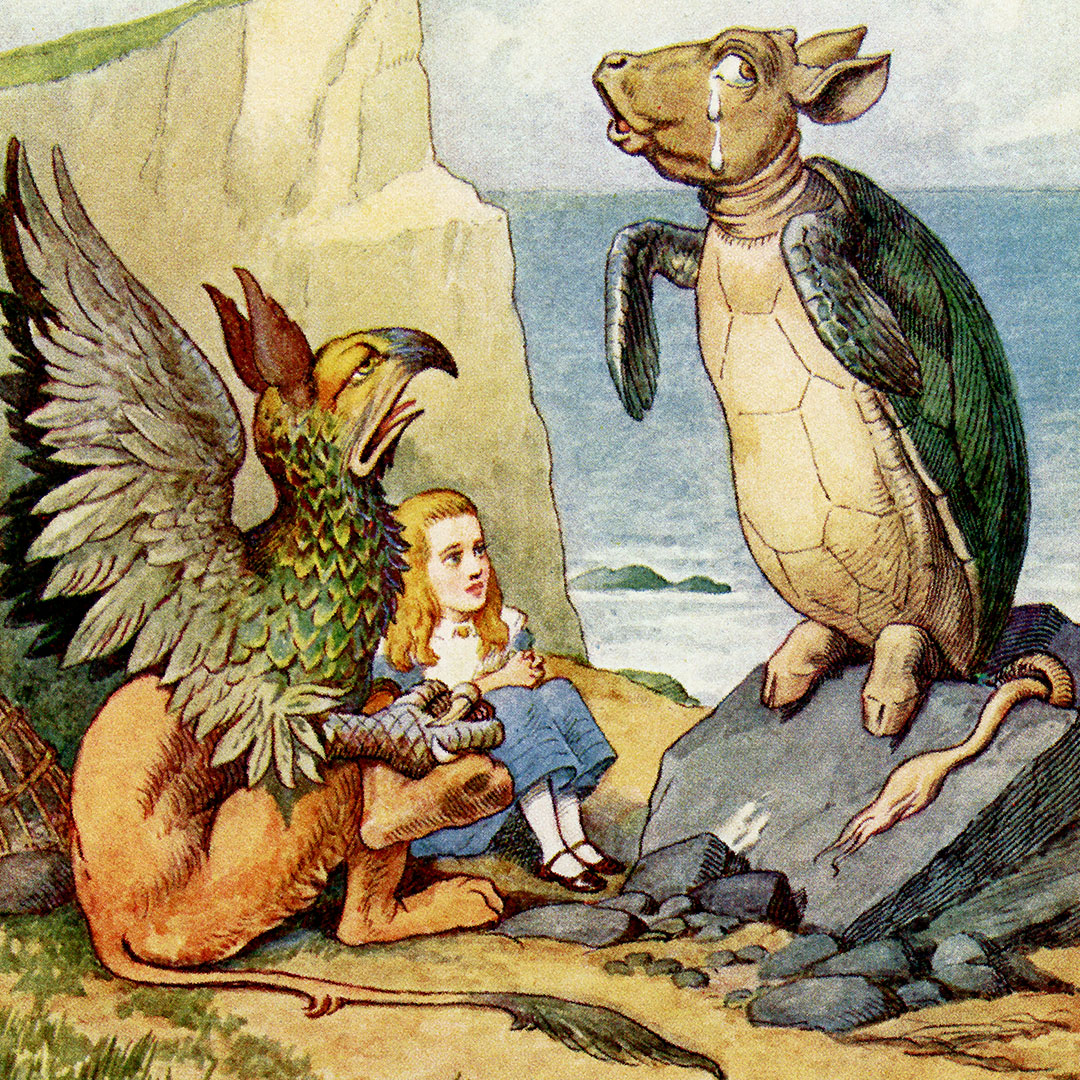

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?Martin Fone delves into the curious tale of an iconic Victorian delicacy: mock turtle soup.

By Martin Fone

-

A game of two halves — how the sandwich went from humble fare to a country-wide lunchtime obsession

A game of two halves — how the sandwich went from humble fare to a country-wide lunchtime obsessionWhat started life as a way to eat and play cards at the same time (so the story goes) is now the lunch of choice for the working world.

By Emma Hughes

-

Where to find the world's best club sandwich — and the story of this triple-layered paean to poolside delight

Where to find the world's best club sandwich — and the story of this triple-layered paean to poolside delightThe club sandwich, arguably the most famous of all sarnies, is a poolside staple, but its origins are tricky to trace, says Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker-Bowles