Curious Questions: Who invented the fork?

Once viewed with suspicion, forks remained the preserve of royalty until nearly 200 years ago. Matthew Dennison takes a stab at the king of cutlery, which changed the way we eat.

Amid a hoard of silver coins discovered in the Wiltshire village of Sevington was a two-pronged silver fork identified by archaeologists as Saxon, pre-dating the Norman Conquest by at least two centuries. Its burial alongside valuable coins points to its status for its first owner.

In the 9th century, a fork was a rarity in English life, evidence perhaps of overseas trading links. There is evidence of forks being used in both ancient China and ancient Greece, but their spread had been slow. By the year 850 — the date of the Sevington fork — they were used by Persian nobles, a habit that had spread across the Byzantine Empire, including to the Byzantine princess who, in 1004, married the Doge of Venice and earned round condemnation for her use of a two-pronged gold fork to spear chunks of food cut up for her by attendant eunuchs. St Peter Damian explained her subsequent death from the plague as God’s judgement on her vanity, a view apparently based on her table manners and eating habits. They soon spread from there to Italy, and would move on to the rest of the Mediterranean over the next few centuries. But in Wiltshire villages, in middle of the ninth century?

Forks are the johnnies-come-lately of British dining tables. Although an inventory of the personal effects of Edward I, made on the King’s death in 1307, included ‘six silver forks, one gold fork, and a pair of table knives with handles of crystal’, centuries would pass before Edward’s countrymen followed the royal example. In 1559, for example, only 12 ‘silver and gilt’ forks were listed in Elizabeth I’s possession; a later inventory records ‘thre[sic] of them Broken’ and no replacements. The earliest known hallmarked silver fork made in an English workshop bears London assay office marks for 1632–33.

In 1606, playwright Ben Jonson set his best-known satire, Volpone, in Venice. For 17th-century Englishmen, whose xenophobia expressed itself robustly, a fork was a foreign affectation particularly associated with Italy and Italians. In Jonson’s play, Sir Politic Would-be advises his fellow traveller Peregrine ‘to learn the use and handling of your silver fork at meals’, an indication of English diners’ lack of familiarity with the pronged implement. When, five years later, in 1611, Thomas Coryat explained the benefits of forks to readers of his travelogue Crudities, for his pains he earned himself the contemptuous nickname ‘Furcifer’, or ‘fork-bearer’. It was all very discouraging.

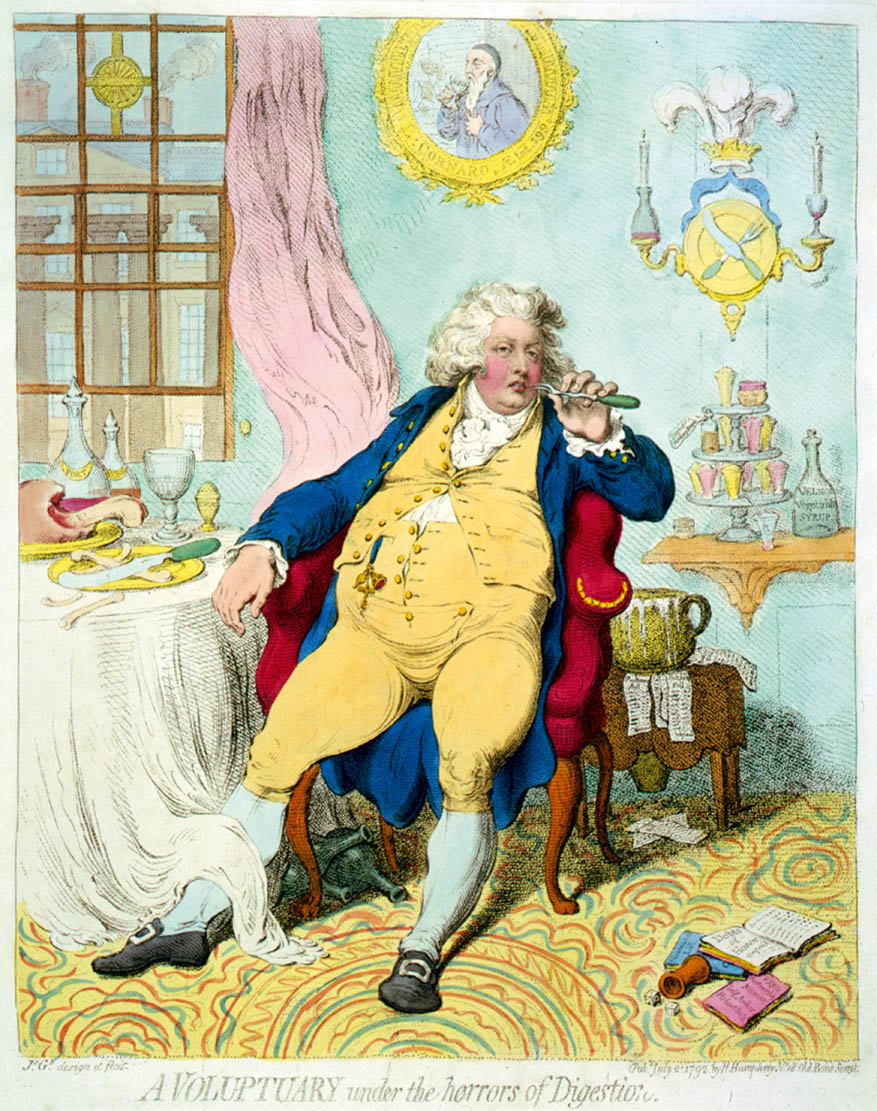

In a nation where, for many, knives, spoons and fingers were adequate to the task of eating — with fingers or the point of a knife used to bring food to the mouth — forks would continue to provoke both ribaldry and disapproval into the next century. Polemicist Peter Heylin referred to ‘the use of silver forks’ taken up ‘by some of our spruce gallants… of late’ in 1652. Whether or not the right-minded reader was intended to aspire to join the company of ‘spruce gallants’ is, it seems, an easy guess. The Ingenious Gentlewoman’s Delightful Companion suggested in 1653 that ‘the accomplished lady’ use a fork rather than her fingers to serve meat to diners — ‘it will be comely and decent’ — but the use of forks as eating, rather than serving, implements did not become universal in Britain until the 19th century.

As so often, elite diners led the way. That a canny Cromwellian silversmith made a lucrative sideline in ‘royal’ cutlery in the mid 1600s is proof of the adoption by Cavalier gentry of the new-fangled fork. Charles Rivet’s bronze-handled knives and forks were, he claimed, made from a statue of Charles I bought by Rivet from Cromwell’s government as scrap. Rivet misled customers that he had melted down the statue (which survives today) and repurposed the metal for his souvenir cutlery, for which he found an eager clientele.

Although the English lagged behind their Continental neighbours, the nation’s reservations about forks were once widely shared. A 16th-century German cleric is recorded as denouncing the fork as a diabolical luxury, arguing that, had God intended men to use forks, He would not have provided them with fingers. Meanwhile, the fork reached France from Italy in the 1530s, following the marriage of the Italian noblewoman Catherine de’ Medici to the future Henri II, but Catherine’s example failed to sway many of her adopted countrymen. Essayist Michel de Montaigne, for example, continued as late as the 1570s to eat with a knife and his fingers, recording that, as a result, when he ate too quickly, ‘I sometimes bite my fingers in my haste’.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A satirical French novel published in 1605 sought to expose the affectations and deceits of the courtiers of Catherine’s son, Henri III. Suffice to say, the King’s attendants ate with forks. Not until 1760 did French cavalry officer François Baron de Tott describe eating with a fork as ‘in the French manner’, a term at last of commendation.

Although its purpose has never changed, the appearance and ergonomics of the fork have evolved over time. Early forks, such as that made by London spoon-maker Richard Crosse in 1632, had two prongs and were undoubtedly more effective for spearing food than enjoyable to use. Three- and four-prong forks appeared from the third quarter of the 17th century, initially with round-section tines, such as the silver-gilt forks supplied to George II in 1740 by silversmith Philip Roker II. By the end of the 18th century, four-prong forks had become widespread, including those made by Francis Higgins who, in 1821, appeared in Robson’s London Commercial Directory as a ‘Silver Fork manufacturer’, Higgins’s decision to specialise proof of the extent of the market for silver forks by this stage.

Did the fork change British eating habits? Thomas Coryat had posited hygienic grounds for the use of forks in 1611, noting that ‘the Italian cannot by any means endure to have his dish touched with fingers, seeing all men’s fingers are not alike clean’. The serving fork eliminated contact between the server’s possibly dirty fingers and a diner’s food, whereas the use of the fork to carry food to the mouth ended a centuries-old habit of eating at least in part with fingers. Jonson had jeered that the use of the fork promised to limit the extent to which diners dirtied their napkins, as hands and fingers remained clean of food.

Time would prove him right and it was not until the advent of widely available fast food in the 20th century that many British diners returned to eating with their fingers. As Frederick Hackwood noted in 1911, in Good Cheer: The Romance of Food and Feasting, ‘the introduction of table forks… had an effect on table manners’, one that, for practical reasons, as well as good manners, seems unlikely to suffer reversal.

Credit: Simon Hopkinson

How to make Simon Hopkinson’s warm, summery salad with asparagus, bacon and an unusual touch of chicken

Tender, pink chicken livers, young asparagus and pea shoots are perfect with a creamy vinaigrette of sherry and Dijon mustard

Jason Goodwin: 'The boys, saucer-eyed, watched the Lord spoon his soup, indifferent to the suffering of his fairy slaves'

Our Spectator columnist considers the House of Lords.

Credit: Graham Day / Getty

In praise of the great British sausage – and five of the best bangers you can buy

Few foods are equally at home on the tables of royalty as they are at the local greasy spoon, but

-

Five outstanding properties, from 3,000 acres in Wales to Robert Plant's old home, as seen in Country Life

Five outstanding properties, from 3,000 acres in Wales to Robert Plant's old home, as seen in Country LifeWe take a look at some of the best houses to come to the market via Country Life in the past week.

-

Ben Randall: Why your dog behaves for some people, but not others

Ben Randall: Why your dog behaves for some people, but not othersAward-winning dog trainer Ben Randall shares his advice with Country Life readers on one of the most common questions he gets asked.

-

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?As April 1 looms, Martin Fone tells the tale of one of the finest stunts ever pulled off.

-

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade when there are more than 400 other varieties available worldwide? And do they really make the best preserve? Jane Wheatley investigates.

-

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this day

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this dayOnce packed with meat, such as ox tongue and mutton, alongside dried and candied fruit and extravagant spices, the mince pie is not what it once was — and food historian Neil Buttery says that's made them worse.

-

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?Margarine has been a staple of our breakfast tables for over a century, but it hasn't always had a smooth ride — particularly from the dairy industry, who managed to impose a most bizarre sanction on their easily-spreadable, industrially mass-produced rival. Martin Fone explains.

-

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?With the UK wine industry booming, Martin Fone takes a look at its history.

-

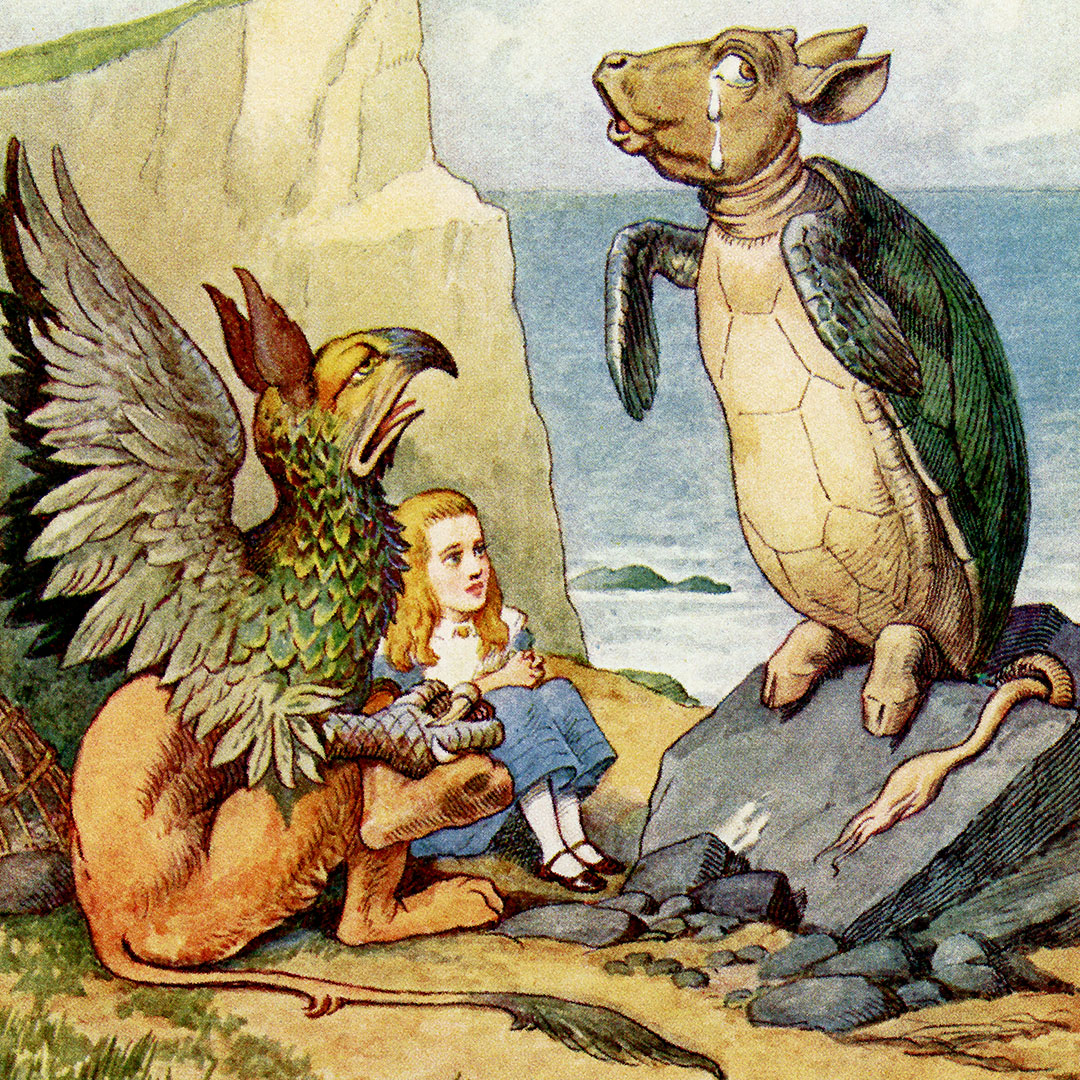

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?Martin Fone delves into the curious tale of an iconic Victorian delicacy: mock turtle soup.

-

A game of two halves — how the sandwich went from humble fare to a country-wide lunchtime obsession

A game of two halves — how the sandwich went from humble fare to a country-wide lunchtime obsessionWhat started life as a way to eat and play cards at the same time (so the story goes) is now the lunch of choice for the working world.

-

Where to find the world's best club sandwich — and the story of this triple-layered paean to poolside delight

Where to find the world's best club sandwich — and the story of this triple-layered paean to poolside delightThe club sandwich, arguably the most famous of all sarnies, is a poolside staple, but its origins are tricky to trace, says Tom Parker Bowles.