When did Stir-up Sunday first begin?

On the last weekend before Advent, families gather to make Christmas pudding on the day we know as Stir-up Sunday. But when did we start giving it that name? With Stir-up Sunday 2023 falling on November 26th, Neil Buttery takes a look.

The tradition of Stir-up Sunday is peculiarly British — nowhere else, apart from some Commonwealth countries, knows what a Christmas pudding is, let alone what Stir-up Sunday might entail, yet both pudding and ritual are fundamental to British food identity. The idea is that every member of the family takes part by adding an ingredient to the bowl or stirring. All rituals have their superstitions: the mixture must be stirred from east to west (the path of the sun across the sky, as well as the direction of travel by the Wise Men) or clockwise (never anti-clockwise, which is going against Nature and, therefore, bad luck).

One might think that such a tradition would go back to time immemorial, yet this practice didn’t become well known until the 1920s. Stir-up Sunday had existed before then, but as a day for stirring up emotions to ready oneself for Advent, a period of prayer and fasting. It was the late Victorians who hijacked it as they attempted to create what they thought a traditional Christmas should be — and if feelings were being stirred up, why not stir up the pudding and make it a family event? They even adapted the accompanying hymn (‘Stir up, we beseech thee, O Lord, the wills of thy faithful people’) to fit this change in focus.

[READ MORE: An ideal Christmas pudding recipe]

The mixture was left to macerate overnight, before being boiled and stored for Christmas. Some puddings reached gargantuan size, requiring a 15-hour boil, and it is because of its long boiling time that few people today make a Christmas pudding. In the 2010s, its popularity dropped so low that some feared it might become extinct. However, the covid pandemic saw pudding popularity soar as consumers hankered for traditional comfort food.

The richness of Christmas pudding may be off-putting for some, but it can take a plainer form and, bearing the name of plum pudding, may be eaten outside the festive period. The core ingredients have remained the same: stale breadcrumbs, flour, suet, raisins, currants, some sugar or treacle and spices, all combined with milk, booze and sometimes eggs. Notice that there are no plums — from the 18th century, the word ‘plum’ applied to the fruit (and the prune), but also to dried fruits in general.

To make a classic Dickensian, cannonball-shaped pudding, the mixture has to be wrapped in a piece of just-wet muslin dredged with flour, tied up tightly and plunged into simmering water. When cooked, it’s turned out, plump and yielding — and, when broken into, a delicious, dark, steamy and soft interior is revealed, like a huge ripe fig, reflecting its other name: figgy pudding.

Its heyday was the 18th and 19th centuries, when it was served as a main-course accompaniment to roast beef. This combination was the national dish, a marriage of home-reared beef and a pudding made from ingredients of the Empire: sugar, spice and dried fruits, the ultimate dish of patriotic pride. It didn’t become associated with Christmas until the Victorian era, when recipes for Christmas pudding began to appear. In the first edition of Eliza Acton’s 1845 classic Modern Cookery for Private Families, there are two recipes for Christmas pudding specifically, all essentially the same as her plum puddings, except for lashings of fruit, booze and sugar.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Because of all the extra sweetness, the pudding started to slide to the end of the meal, detaching it from the roast beef of old England. Some say a Christmas pudding should have 13 ingredients (for Jesus and his 12 disciples) and it possibly did for a while, but, once we hit the 20th century, there were more; in the 1930s, George V had an ‘Empire Pudding’ made for him containing 17 ingredients and, since then, rich puddings have been the norm (rationing during the Second World War aside).

If you enjoy sweet things, but find the shop-bought, over-rich Christmas puddings too much, you should hunt out one of Acton’s simpler recipes and get back to your pudding roots — you won’t be sorry.

Credit: © Giles Christopher / Media Wis

How to make a show-stoppingly festive Bailey's chocolate cake

Wow your harshest judges with Star Baker Edd Kimber's decadent chocolate cake, perfect for a Christmas pud.

Tried and tested: the best non-supermarket Christmas puddings

The proof is in the pudding.

Credit: Ultimate Christmas Day food - Illustration by Sholto Walker

A gourmand's Christmas dream: The ultimate day of indulgence, from midnight to midnight

Self-confessed bon viveur Mark Priceis a firm believer in indulgence, and at Christmas he pushes it to the next level.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotels

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotelsWhen it comes to hotel design, the Brits do it best, says Giles Kime.

By Giles Kime Published

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino Published

-

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?As April 1 looms, Martin Fone tells the tale of one of the finest stunts ever pulled off.

By Martin Fone Published

-

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade when there are more than 400 other varieties available worldwide? And do they really make the best preserve? Jane Wheatley investigates.

By Jane Wheatley Published

-

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this day

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this dayOnce packed with meat, such as ox tongue and mutton, alongside dried and candied fruit and extravagant spices, the mince pie is not what it once was — and food historian Neil Buttery says that's made them worse.

By Neil Buttery Published

-

Tom Parker Bowles: Forget turkey and pigs-in-blankets — the Christmas ham is the king of the yuletide feast

Tom Parker Bowles: Forget turkey and pigs-in-blankets — the Christmas ham is the king of the yuletide feastRibboned with fat and gleaming with a clove-studded glaze,Tom Parker Bowles sings the praises of the succulent Christmas ham.

By Tom Parker-Bowles Published

-

What to get the wine lover who has everything? How about a 300-bottle barrel, a string of über-vintages or a wine that comes with a trip on a private jet

What to get the wine lover who has everything? How about a 300-bottle barrel, a string of über-vintages or a wine that comes with a trip on a private jetOne of the most storied wine-producing families in Italy has put up a series of rather incredible bottles (and more) in Christie's impending fine wine auction.

By Toby Keel Published

-

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?Margarine has been a staple of our breakfast tables for over a century, but it hasn't always had a smooth ride — particularly from the dairy industry, who managed to impose a most bizarre sanction on their easily-spreadable, industrially mass-produced rival. Martin Fone explains.

By Martin Fone Published

-

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?With the UK wine industry booming, Martin Fone takes a look at its history.

By Martin Fone Published

-

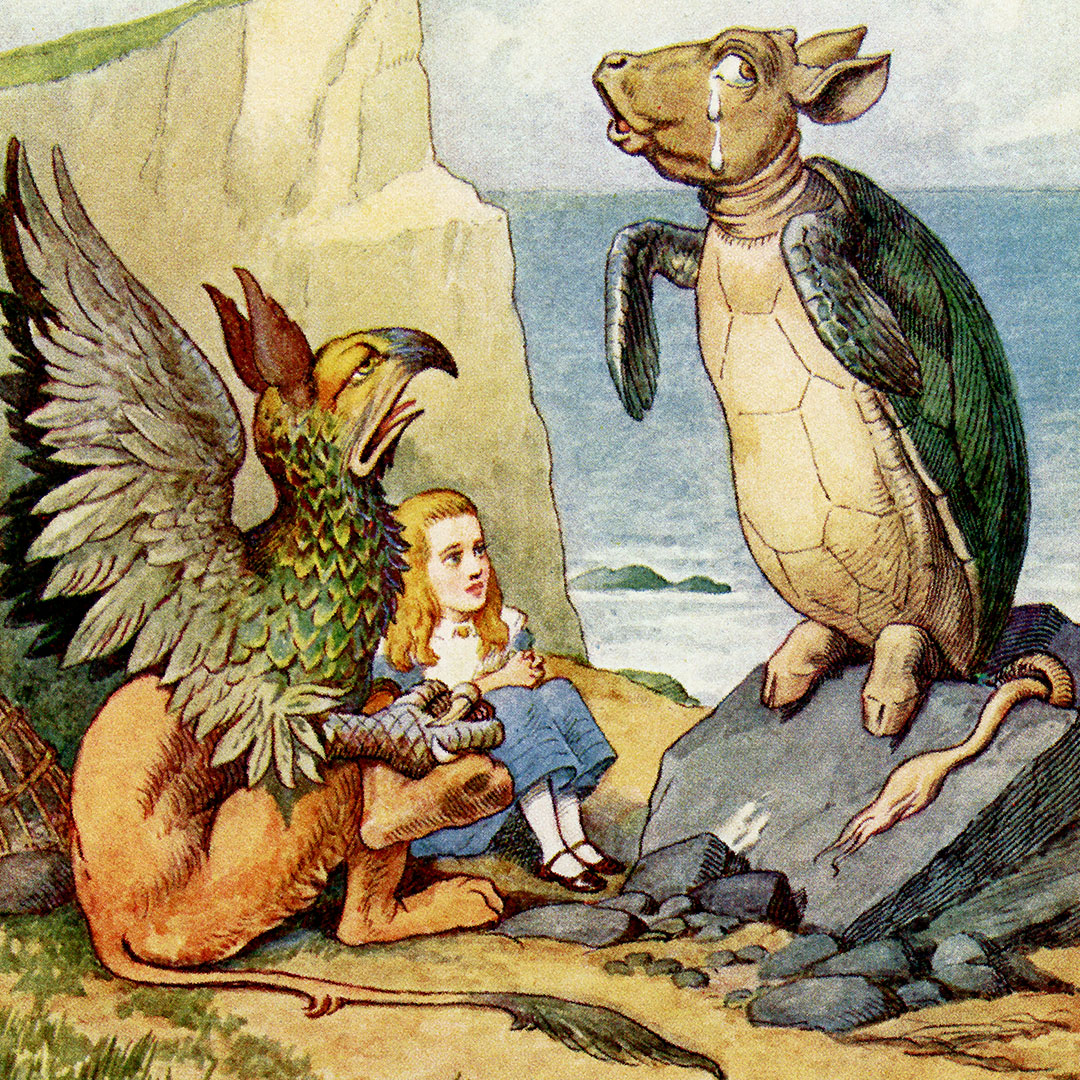

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?Martin Fone delves into the curious tale of an iconic Victorian delicacy: mock turtle soup.

By Martin Fone Published