Curious Questions: What is Worcestershire sauce’s secret ingredient?

The world-famous Worcestershire sauce owes a great deal to a product that comes a very, very long way from Worcestershire itself, as Martin Fone discovers.

A thin brown, savoury, tangy, spiced sauce, a delightful hit of umami in a bottle, Worcestershire sauce is firmly established as one of the world’s leading condiments with global sales of $805.6 million in 2021. While following in the footsteps of fermented fish sauces like garum, the ketchup of the Roman world, it was created purely by chance, or so the story goes.

John Lea and William Perrins had run a chemist shop in Broad Street in Worcester since 1823. One day, they were visited by Lord Marcus Sandys who had recently returned to the family seat at nearby Ombersley Court after a spell as Governor of Bengal. While out in India he had developed a taste for a particular sauce which he asked the chemists to reproduce from a recipe he had obtained.

Chemists rather than chefs, Lea and Perrins did their best, but without the precise quantities of the ingredients what they produced they found, according to the Lea & Perrins website, to be ‘completely unpalatable’. The fish and vegetable mixture had such a strong and unpleasant smell that they stored it in their cellar and promptly forgot about it. It was only rediscovered some eighteen months later, by which time it had matured into a delicious sauce.

Recognising the commercial possibilities of their sauce, Lea and Perrins bottled it in the only containers they had available, their round medicine bottles. The distinctive bottle shape with its long neck is still used today. Launched locally in 1837, their sauce proved to be such a hit that they had to take over the premises next door to manufacture the quantities required.

One of their early marketing ploys was to arrange for all ocean-going liners travelling to and from England to stock Worcestershire sauce in their restaurants, even paying waiters to serve it. By 1839 the sauce had reached the United States and so popular was it that the importer, John Duncan of New York, opened a processing plant, bringing the ingredients from England, and manufactured the sauce exactly to Lea and Perrins’ formula. The American version nowadays, though, is different, using distilled white vinegar instead of malt vinegar, three times more sugar and more than three times as much sodium.

"Its peculiar piquancy, combined with its exquisite flavour, establish it of a character unequalled in the sauces"

Doubt has been cast on the veracity of this version of the sauce’s origin, as the informative blog, The Heart Thrills, points out. There is no record that Lord Marcus, who was not elevated to the peerage until 1860, ever went to Bengal, let alone serve as its governor, nor did any of his immediate family. Nor was the idea of creating an anchovy-based sauce unique to Lea and Perrins.

As early as 1747 Hannah Glasse included in her The Art of Cookery Made Plain & Easy a recipe for Anchovy Sauce, while in 1830 Dr William Kitchiner gave a recipe in his The Cook’s Oracle and House Keeper’s Manual for Fish Sauce, which he had received from a ‘very sagacious sauce-maker’. Kitchiner’s sauce called for six anchovies pounded, two wine glasses of port, two of walnut pickle, four of mushroom catsup, sliced and pounded eschalots, a tablespoonful of soy, and half a drachm of Cayenne pepper. The ingredients were simmered gently for ten minutes, the liquid strained, and when cold, bottled and corked.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Even an Indian twist was not unique to Lea and Perrins. Since 1830 rival Worcester chemists, Twinberrow and Evans, had been selling a sauce they had developed which pandered to the growing demand for condiments spiced with the flavours of India. Meanwhile Worcester sauce was a term used to describe the sauces that local traders used to make to complement the taste of a delicacy, lampreys, which were caught in the River Severn.

The precise ingredients of Lea and Perrins’ sauce remain a closely guarded secret, the bottle’s labelling being both helpful and vague. It lists malt vinegar, spirit vinegar, molasses, sugar, salt, anchovies, tamarind extract, onions, garlic, and various assorted and unnamed spices and flavourings, but there is no indication of quantities used.

The replacement of walnut pickle and mushroom catsup, a form of ketchup, with tamarind extract, a staple of Bengali cuisine, might have given Lea and Perrins’ sauce its Indian twist, allowing them to spin the tale of its exotic origin. In truth, though, it seems to have been a variant, or to use the modern culinary parlance, an elevation of some of the anchovy-based sauce recipes already extant.

Those with a heightened sense of taste believed that soy, which featured in Kitchiner’s recipe, was a key but undisclosed ingredient in Lea and Perrins’ sauce. The first to claim its presence in print was Allan Forman who wrote in an article in the Washington Post on July 25, 1886, that soy sauce was used ‘from the East Indies to England, where it is still more spiced and flavoured and patriotically called Worcestershire sauce’. Curiously, its presence was highlighted by its absence, supply difficulties of soy experienced during the Second World War led to its replacement by hydrolised vegetable protein.

Although Lea and Perrins have never explicitly named soy as a key ingredient in their Worcestershire sauce, proof positive was provided by a company ledger from 1907, rescued from a skip by Brain Keogh, archivist and author of The Secret Sauce (1997). A page headed ‘Return to old formula’ gave the recipe together with quantities, revealing that the principal ingredients were 2.5 parts of vinegar and to one of soy. The rubric at the top of the page of the ledger, now on display at the Worcester City Art Gallery and Museum, suggested that this had been the case for decades.

An advertisement in the Observer of March 5, 1843, the first independent evidence of the sauce’s existence, claimed that Lea and Perrin’s Worcestershire Sauce, ‘prepared from the recipe of a nobleman in the country’ had been ‘steadily progressing in public favour; its peculiar piquancy, combined with its exquisite flavour, establish it of a character unequalled in the sauces’, especially ‘for enriching gravies or as a zest for fish, curries, steaks, game, cold meat etc’. It was sold in three sizes, half-pint bottles costing 1s 6d, pints 2s 6d, and quarts at 5s, each ‘with the Proprietors’ stamp over the cork of every bottle’.

By 1866 Lea and Perrins had sold their chemist shops, concentrating their efforts on making and selling their sauce, which was becoming increasingly popular worldwide. Their success encouraged rivals to produce their own version of the sauce. To protect their brand Lea and Perrins introduced a new label in 1875 bearing their signature, ‘without which’, they warned, ‘none is genuine’.

They also resorted to legal action to deter competitors from branding their sauce Worcestershire. However, the High Court ruled that they did not own ‘the rights to the name ‘Worcestershire’ in connection with a sauce such as that made by their company’, noting that since the sauce’s launch in 1837 ‘other people, of whom one Batty seemed to be the first, began to sell an article under the same name’ (Times, July 26, 1876).

Nevertheless, the name of Lea and Perrins is synonymous with Worcestershire sauce today. I just wonder why they are so coy about soy.

Credit: Getty Images/Image Source

Curious Questions: Why is the pork pie associated with Melton Mowbray?

Martin Fone tells the tale of a true British culinary classic: the pork pie.

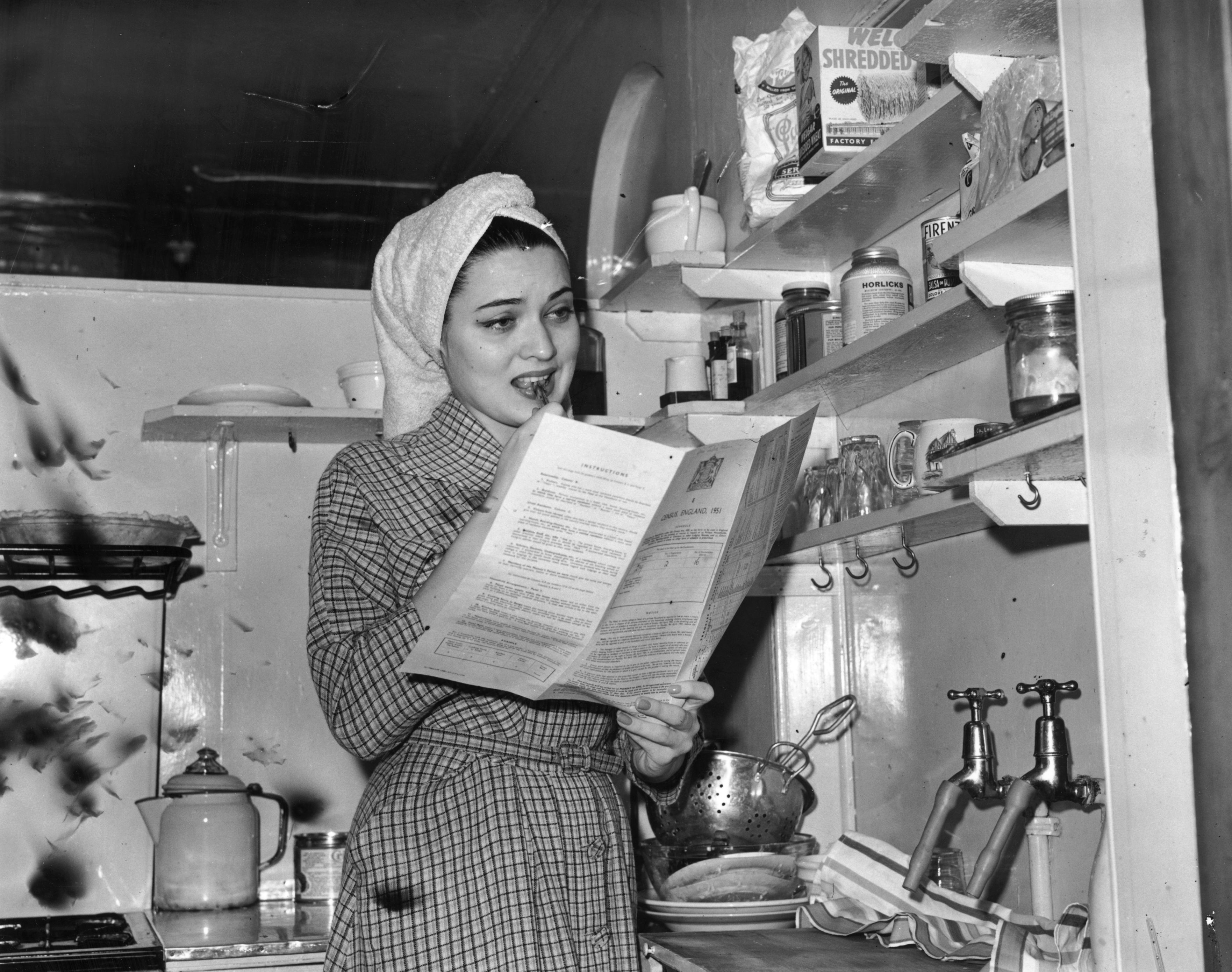

Curious Question: When was the first census held?

As the UK prepares to compile this decade's census, Martin Fone retraces its history.

Curious Questions: Why were ferns considered magical?

Martin Fone considers the beautiful and ancient fern, once commonly held to have mysterious properties.

Curious Questions: How likely are you to be killed by a falling coconut?

Our resident curious questioner Martin Fone poses (and answers) another head scratcher - or should we say, head banger?

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.