Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?

Martin Fone delves into the curious tale of an iconic Victorian delicacy: mock turtle soup.

It all began out of necessity. In the early 18th century, on discovering that they were edible, British sailors in the Caribbean kept live green turtles on board their ships to ensure a supply of fresh meat. News of this exotic meat, offering cuts whose flavours were reminiscent of veal, beef, ham, and pork, soon spread to their homeland. By the middle of the century some 15,000 live turtles were being imported a year to satisfy the culinary cravings of the English aristocracy, the ‘most outspoken in their praise of this sea creature’s virtue’ as food.

Particularly sought after was turtle soup, a dish that appeared as regularly as clockwork on the menu for the Lord Mayor’s Day Banquet in London from 1761 until 1825. With its dull-green colour, delicate taste, and gelatinous feel in the mouth, it became so popular that turtle-shaped tureens were produced specifically for its presentation at table on formal occasions.

One of the first to publish a recipe for turtle dressed ‘in the West India way’ was Hannah Glasse in her 1751 edition of The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy. As well as a recipe for soup there were others which made use of particular cuts of turtle meat, one for the calipash or back shell, another featuring the calipee or belly, another that made use of the offal and one for the fins. Each dish was allocated a particular spot on the table for service.

Elizabeth Raffald, in The Experienced English Housekeeper (1769), showed how a hundred pound turtle could be used to prepare seven dishes. The first course should be of turtle on its own, she informed her readers, but thereafter the various cuts could be intermingled with other fare or presented in isolation, either approach, she wrote reassuringly, being ‘sure to be met with approval from the guests’.

For those unsure how to prepare a turtle for cooking, cookery books were unsparing in their gory detail. Beheading or throat-slitting were the preferred methods, according to Amelia Simons’ American Cookery (1796), remembering to retain the blood, after draining, to add some extra flavour to the soup. The fins were then removed, the calipee cut off, and the meat, bones, and entrails removed from the back shell, except for the green fat, known as the monsieur. This was baked on to the shell, from which the soup was served for an enhanced taste.

The consumption of green turtles became so synonymous with the extravagant and luxurious lifestyles of the Georgian rich that it was seized upon by political satirists who contrasted it with the poor fare eaten by the masses. They also pointed out with glee that eating turtle meat was not without its dangers, occasionally leading to chlenotoxism, a type of blood poisoning which can be fatal and for which there is no known antidote. In a case of biter bit, they would portray a diner suffering a sudden and swift death at the dining table.

A print from 1799 combined both these themes, showing an alderman enjoying a bowl of turtle soup while being grabbed by the throat by a skeleton representing Death. ‘Come, old boy’, the skeleton exclaims, ‘you have play’d an excellent knife and fork – you cannot grumble – for you have devoured as much in your time as would have fed the Parish poor’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the mania for turtle meat in Britain and, later, in Germany resulted in overfishing, wiping out stocks of green turtles in their native habitats, pushing up their prices to astronomic levels and leading, ultimately, to their general unavailability. The hunt was on for a suitable alternative.

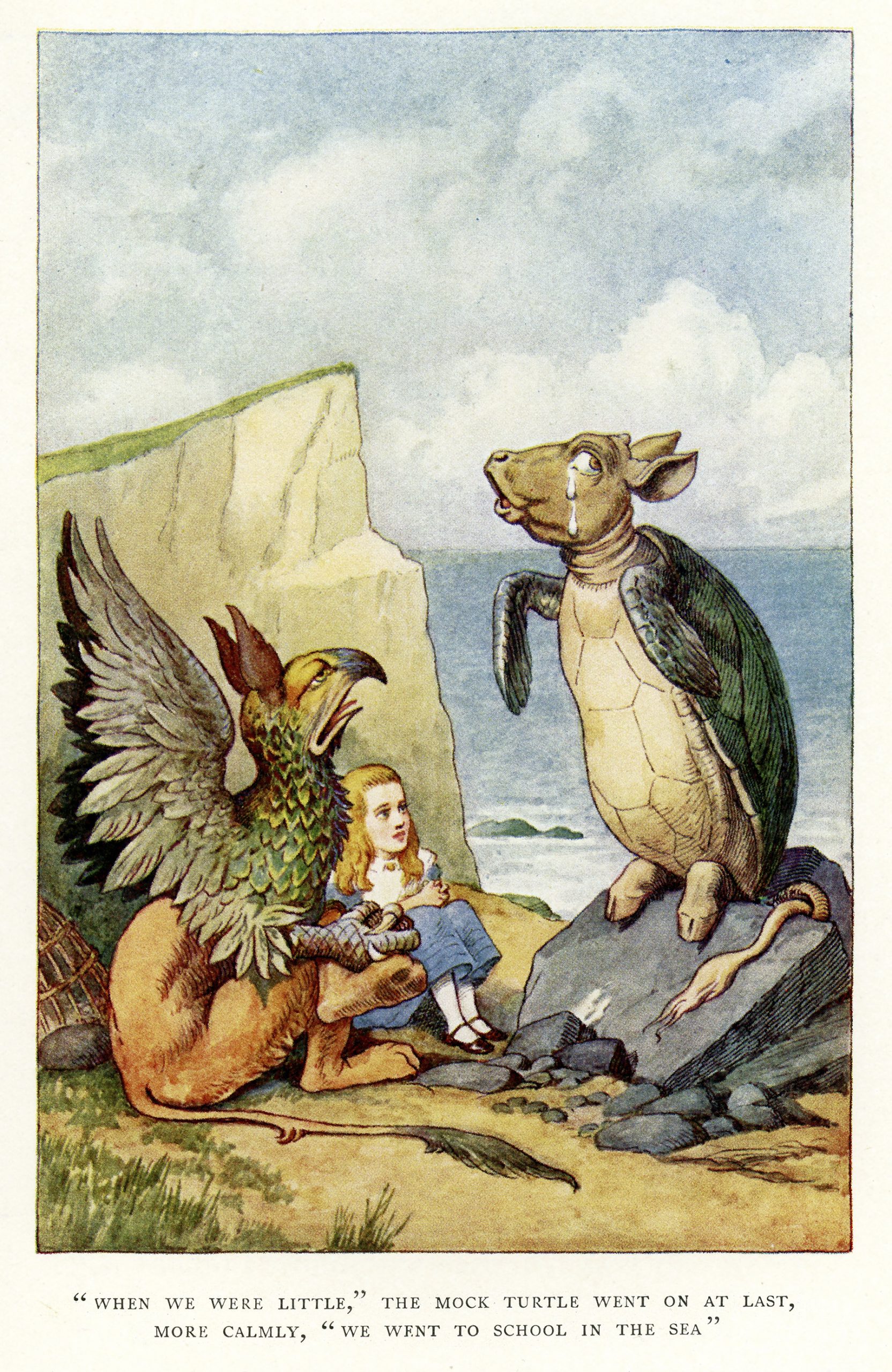

A clue to the solution is provided in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), in which Lewis Carroll’s eponymous heroine is famously introduced to the Mock Turtle by the Queen of Hearts. John Tenniel’s accompanying illustration shows him as a mélange of various creature’s parts, a calf’s head on the body of a turtle and feet which look suspiciously like pig’s trotters.

Even at the height of the British turtle soup mania, recipes began to appear for mock turtle soup, a soup which supposedly mirrored the taste of turtle but was made from more economical and readily available ingredients. Of the five turtle recipes in the 1773 edition of Eliza Smith’s The Compleat Housewife, or, Accomplished Gentlewoman’s Companion, two were for mock turtle.

The principal ingredient was a calf’s head, which offered an equally varied range of flavours and textures. Most recipes were particular about the need to keep the skin on to ensure that the soup benefited from its fats. Of course, the humble calf’s head soup had been around for centuries but rebranding it as mock turtle gave it extra cachet.

To enhance its flavour, other ingredients were added, the White House cookbook of 1887 recommending sherry, cayenne pepper, lemon, sugar, salt, and mace. Crosse and Blackwell marketed ‘a special selection of Herbs for Turtle Soup’, initially intended for use in the preparation of real turtle soup but by the early decades of the 20th century a valuable addition to the mock version.

Fancy restaurants also got into the act of passing off a soup made from cheap cuts that might otherwise have been discarded as a high-end dish and charging accordingly. In 1900 a Manhattan restaurant called Sullivan’s was offering its diners a bowl of mock turtle soup for fifteen dollars; they charged only ten for tomato, chicken or oxtail.

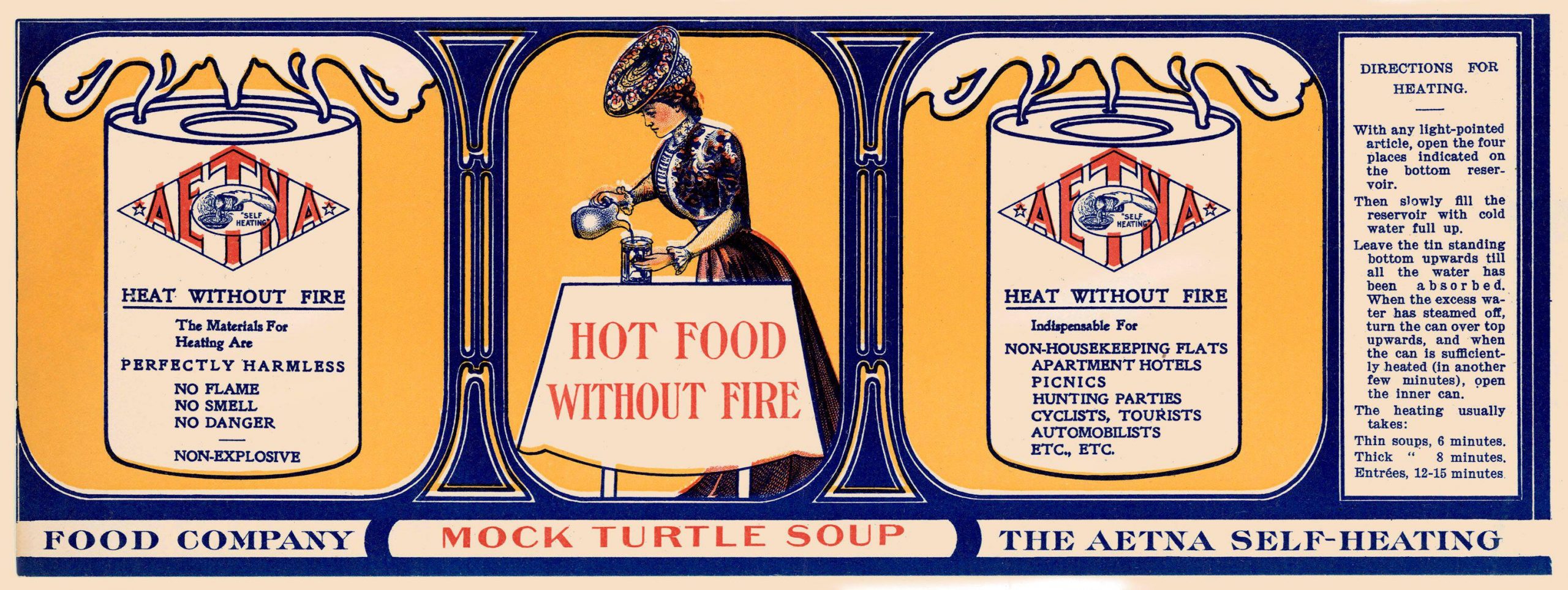

More manageable than a whole turtle to prepare in a household kitchen, it was still a painstaking operation, the meat having to be extracted from the skull, boiled to tenderness and then left standing overnight. With the dawn of convenience foods in the 20th century, soup manufacturers such as Heinz and Campbell’s added mock turtle soup to their range, the latter promising a product with a ‘tempting, distinctive taste so prized by the epicure’.

By the 1960s, though, even mock turtle soup had fallen out of favour, perhaps because the idea of eating anything vaguely associated with a turtle had become abhorrent. One who mourned its fall from grace was Andy Warhol, who, in a 1962 interview, confessed that mock turtle was his favourite. ‘I must have been the only one buying it’, he lamented, ‘because they discontinued it’.

While the luxury passenger liner, SS United States, was still offering its passengers mock turtle soup in the 1960s and real turtle soup even appeared on the menu for the Independence day celebrations on board the SS Canberra in 1973, public taste had moved on. Though not, apparently, in Cincinnati.

With many of the major abattoirs in the Mid-West situated there to ensure a plentiful supply of calves’ heads and a large German migrant population who valued its sweet-sour taste, Cincinnati became the mock turtle soup capital of the United States. Made from ground beef rather than offal, it is still served today in restaurants and at festivals. For those yearning for a bowl at home, a local Cincinnati company, Worthmore, has been making a canned version of the soup since 1920 using a recipe, which includes lean beef, hard-boiled eggs, lemon zest, and ketchup. They are still selling hundreds of cases a week.

This is the nearest the curious are going to get to the taste of turtle — a mania that, thankfully, has long passed and surely will never return.

[colletion]

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.