Curious Questions: Was there a real Granny Smith who first cultivated the apple that bears her name?

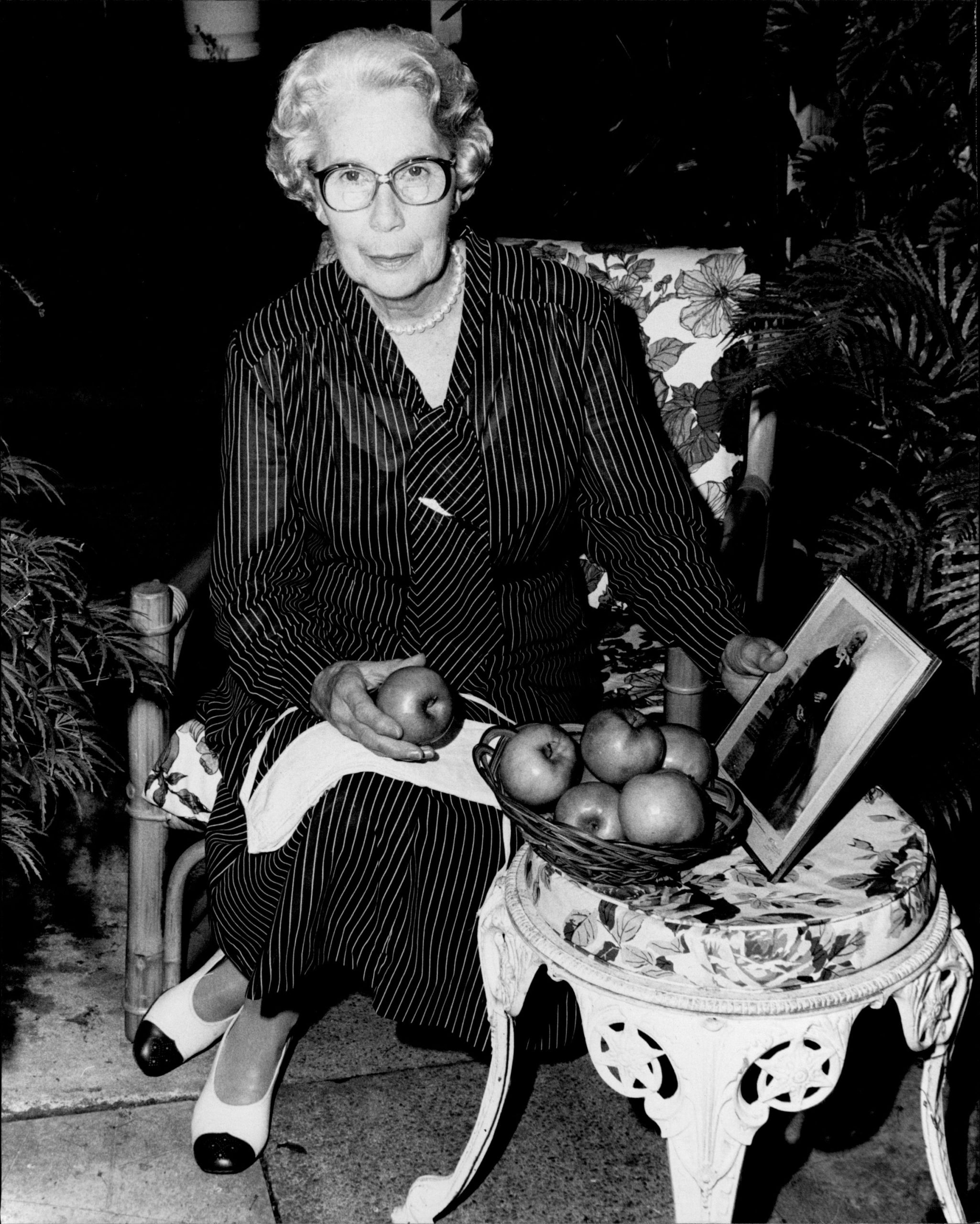

Martin Fone crunches into a tart, crisp apple and ponders a question: who was Granny Smith? And did she really discover the apple that's named after her?

My mother was a ‘firm’ believer in the motto ‘an apple a day keeps the doctor away’. As well as an apple, as a child I was given a large spoonful of a glutinous malt extract syrup and a vitamin C supplement tablet. Whether this daily regimen made me any healthier than I would otherwise have been, I do not know, but it certainly kept the doctor away; I had to go and see him. Although — perhaps in a show of filial rebellion — I rarely eat apples these days, my mother continued the habit until her final days.

Her apple of choice had a distinctive shiny light green hue with a hard skin and crisp, juicy flesh. Tart and acidic to the taste, the Granny Smith was extremely versatile. Not only delicious when eaten raw, its propensity to remain firm when cooked and with its acidity counterbalancing the sweetness of pastry, it was ideal for an apple crumble, which, with lashings of thick custard, was much my preferred method of ingesting the fruit. And it is the healthy option, studies showing that it has a higher level of beneficial antioxidants than other types of apple.

Fashions, though, have changed, not least because supermarkets prefer to have their shelves brightened up by more vibrant bi-coloured varieties of apple. Even my mother followed suit, transferring her affections to the Cripps Pink, an apple marketed as Pink Lady. A cultivar from the Lady Williams and Golden Delicious varieties, it is considerably sweeter and easier on the teeth, becoming the world’s most popular variety of apple, pipping the Granny Smith into second place.

Nevertheless, around 60,000 tonnes of Granny Smiths are still harvested in Australia each year. To ripen successfully, its trade-mark apple-green skin requires warm days and nights and so cultivation is restricted to the apple-growing regions of the southern hemisphere, France, and the warmer zones of North America.

But who was Granny Smith?

Maria Ann Sherwood was born in Peasmarsh in Sussex in 1799, working on a farm from an early age. When she was nineteen, she married Thomas Smith, another farm labourer, and settled down in Beckley, where they had eight children, five of whom survived. The area was famous for its fruit farms and records suggest that Smith’s father held the tenancy of Cherry Gardens in Beckley, a farm on which pears and hops were grown.

In the decades which followed the end of the Napoleonic Wars, life was hard for workers seeking to make a living from the land. Demobbed soldiers and sailors flooded the labour market and those jobs that were available were insecure and poorly paid. The introduction of mechanisation, particularly threshing machines, restricted opportunities still further, leading to the wholesale destruction of the machines, the burning of hay ricks, and the maiming of cattle in riots that swept South East England in the autumn of 1830. The so-called Swing Riots, named after the fictitious Captain Swing, — whose name was appended to letters warning farmers to expect a visit from the rioters — were eventually suppressed. The justice meted out to those arrested was harsh, at least at first: 252 of them were sentenced to death. In the end, however, ‘only’ nineteen were hanged, 644 were imprisoned, and 481 transported to Australia.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Australia, though, was not just a dumping ground for undesirables but also a potential solution to the problem of the agricultural poor. In the late 1830s the New South Wales government launched a ‘Bounty Scheme’, offering anyone prepared to make a go of it down under the princely sum of £25. And in 1838, the Smiths took up the offer.

They collected together their worldly goods and their five children to be one of fifty families who boarded the Lady Nugent for a new life, landing in Sydney on November 27th. Thomas worked in the fruit-growing district of Kissing Point and, by 1856, had earned enough to buy 24 acres of land for £605 near Eastwood, now a suburb of Sydney, which he converted into an orchard.

How precisely Maria developed the apple that bears her name is not known for certain. As with many a discovery it was almost certainly due to happenstance. She was a good cook, famed for the quality of her apple pies, some of which she sold at the local market. One story goes that Maria was given a box of French Crab apples which had been grown in Tasmania. Finding that some of the contents had gone bad, as was her wont, she threw them out in a rubbish tip by the side of a creek which ran through the property. Another suggests that she was experimenting with crab apples as a filling for her pies and discarded those that did not suit out of the kitchen window.

Either way, a seedling developed. Using her skills learned on the fruit farms, Maria was able to nurture the young plant to the fruiting stage. To her amazement, she realised that the fruit was no ordinary crab apple, having ‘all the appearances of a cooking apple’ but also ‘sweet and crisp to eat’. The strain of crab apple had probably cross-germinated with a cultivated apple, with the traits of the crab predominant. It has never been successfully replicated since.

Pleased with her apple, Maria sold them on her stall where they stored ‘exceptionally well and became popular’. In 1868, at her request, a local horticulturist, E H Small, inspected the fruit and declared it to be a new species of apple. Sadly, Maria died two years later, and when Thomas followed her in 1876, the land was bought by a local fruit farmer, Edward Galliard, who extended the planting of the trees that produced Maria’s unique apple.

Sold locally, they developed a growing reputation for their quality and Galliard exhibited them, under the name of ‘Smith’s Seedlings’, at the Castle Hill Agricultural and Horticultural Show in 1890. Renamed ‘Granny Smith’s Seedling’, it was awarded the prize for ‘best cooking apple’ the following year.

Recognised as a cultivar by the New South Wales Department of Agriculture in 1895, it stood out from its competitors as a late-picking cooking apple which, given its long shelf life and hard skin, was ideal for storing as it did not bruise easily. More importantly, it was ideal for transporting long distances at any time of the year — a beneficiary of the boom in demand for Australian-produced food that developed after the First World War. By 1935 it had found a market here in Britain and in 1975 accounted for 40% of Australia’s apple crops.

The denizens of Eastwood are rightly proud that their suburb is the birthplace of the Granny Smith, holding an annual festival on the third Saturday of October to celebrate the start of the fruiting season, a custom that began in 1985.

Maria may not have lived to see the fruits of her chance discovery, her genius being to spot the significance of the apple, but her legacy lives on. The mutation was unique, and every Granny Smith apple is grown on a tree that owes its origin to a cutting from Maria’s original.

Curious Questions: How likely are you to be killed by a falling coconut?

Our resident curious questioner Martin Fone poses (and answers) another head scratcher - or should we say, head banger?

Credit: Alamy

Curious Questions: Why are pineapples called pineapples, when they're not pines and not apples?

Martin Fone delves into the curious history of one of the world's most popular tropical fruits.

Curious Questions: Why does nobody know where Christopher Columbus is buried?

He's one of the most famous human beings ever to walk the planet, but the final resting place of the

Credit: apples and oranges Photo by Best Shot Factory/REX/Shutterstock

Curious Questions: Can you actually compare apples and oranges?

It's repeated so often these days that we've come to regard it as a truism, but are apples and oranges

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagne

'Monolithic, multi-layered and quite, quite magnificent. This was love at first bite': Tom Parker Bowles on his lifelong love affair with lasagneAn upwardly mobile spaghetti Bolognese, lasagne al forno, with oozing béchamel and layered meaty magnificence, is a bona fide comfort classic, declares Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker Bowles

-

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025

Country houses, cream teas and Baywatch: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 24, 2025Thursday's Quiz of the Day asks exactly how popular Baywatch became.

By Toby Keel

-

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?As April 1 looms, Martin Fone tells the tale of one of the finest stunts ever pulled off.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade when there are more than 400 other varieties available worldwide? And do they really make the best preserve? Jane Wheatley investigates.

By Jane Wheatley

-

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this day

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this dayOnce packed with meat, such as ox tongue and mutton, alongside dried and candied fruit and extravagant spices, the mince pie is not what it once was — and food historian Neil Buttery says that's made them worse.

By Neil Buttery

-

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?Margarine has been a staple of our breakfast tables for over a century, but it hasn't always had a smooth ride — particularly from the dairy industry, who managed to impose a most bizarre sanction on their easily-spreadable, industrially mass-produced rival. Martin Fone explains.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?With the UK wine industry booming, Martin Fone takes a look at its history.

By Martin Fone

-

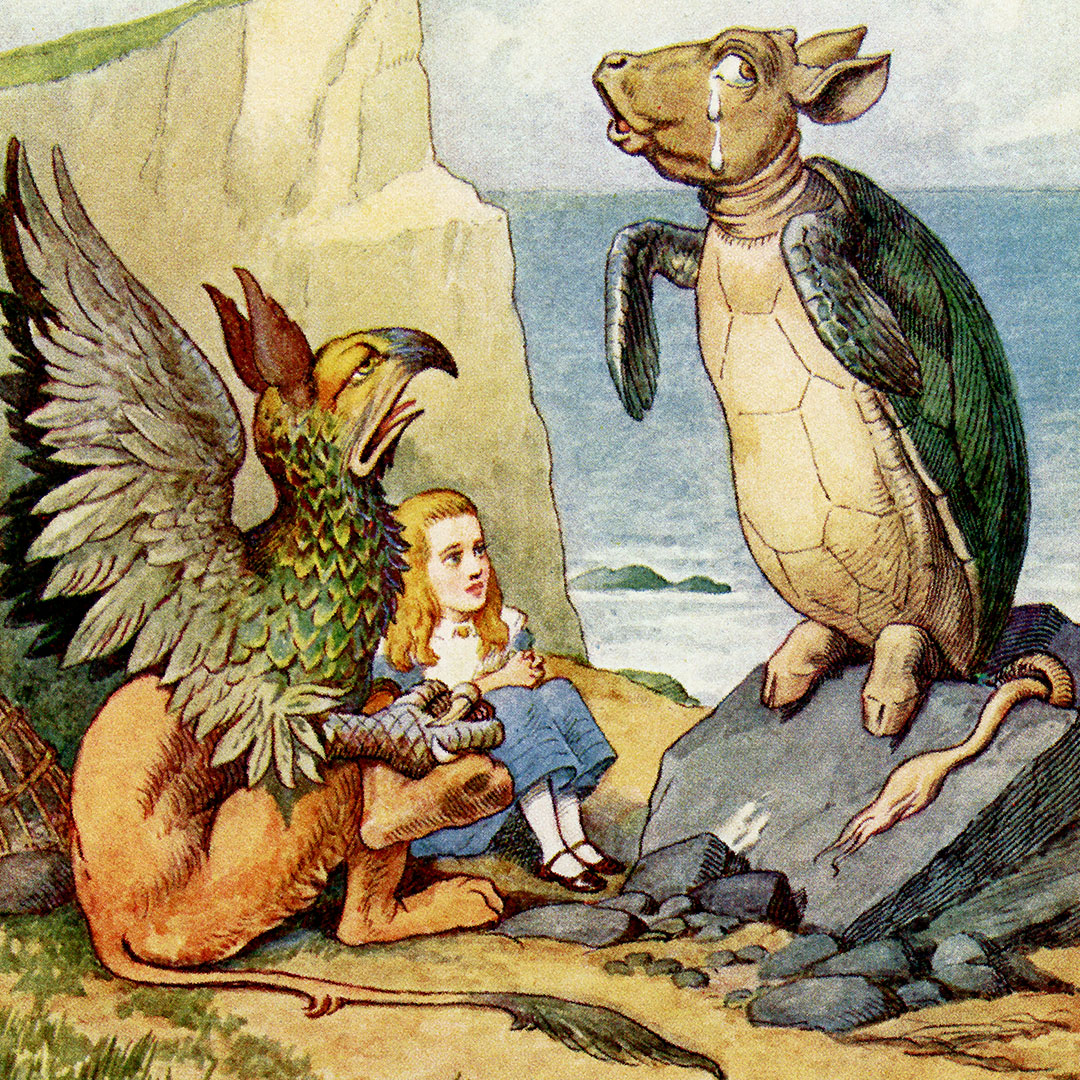

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?Martin Fone delves into the curious tale of an iconic Victorian delicacy: mock turtle soup.

By Martin Fone

-

A game of two halves — how the sandwich went from humble fare to a country-wide lunchtime obsession

A game of two halves — how the sandwich went from humble fare to a country-wide lunchtime obsessionWhat started life as a way to eat and play cards at the same time (so the story goes) is now the lunch of choice for the working world.

By Emma Hughes

-

Where to find the world's best club sandwich — and the story of this triple-layered paean to poolside delight

Where to find the world's best club sandwich — and the story of this triple-layered paean to poolside delightThe club sandwich, arguably the most famous of all sarnies, is a poolside staple, but its origins are tricky to trace, says Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker-Bowles