Curious Questions: How do you make the perfect slice of toast?

Lightly golden, charred at the edges, hot and dripping with melted butter or cold with a thick topping of the stuff? Rob Crossan evaluates the ultimate way to make toast — and pays tribute to the men and women who made it our go-to snack of choice.

No matter how many times you’ve done it, the denouement is always startling. Hot, comforting and defiantly naughty, a hot, crisp slice of bread bursting out of a pop-up toaster has an extraordinary capacity to deliver pleasure and surprise.

Surprise because, although habit should deaden us to the accompanying noise, our bodies never quite seem to learn. When that analogue, spring-loaded clatter of toast leaps up, our first reaction is to jump.

Our second, which arrives just as swiftly, is to start devouring potentially endless slabs of what is, regardless of our age, status or state of wellbeing, a humble, yet unimpeachable champion of comfort food.

Toast is the great leveller, whether you’re an early riser, a nocturnal pub returnee, a bathrobe-clad sleepyhead, a freshly heartbroken shadow or an economically strapped bohemian. Put two slices of white bread into the slot, push down the lever and you’re guaranteed that, within a few minutes, the world will feel an incrementally kinder sort of place.

There’s science behind those slices — 94.2 million of which are eaten by Britons every single day — but the true toast trailblazer has been all but forgotten by history.

It began in an anonymous factory in Still-water, a city in Minnesota, US, a century ago. One day, a mechanic called Charles Strite decided to take decisive action against the endless burnt toast on offer in the canteen.

He intended to improve upon the primitive prototype toasting machine already on the market. This consisted of an uncovered, enclosed wire grid into which users would insert bread and then flip by hand, trying not to burn themselves in the process.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A variable timer and springs were all part of Strite’s 1919 patent, putting the vital ‘pop-up’ prefix onto the toaster. Originally intended to be sold purely to the restaurant trade, Strite’s automatic pop-up was a huge success in the home on its eventual release in 1926. Adverts from the time proclaimed that the Toastmaster 1-A-1 delivered ‘perfect toast every time — without watching, without turning, without burning’. The only thing missing was sliced bread itself, which wouldn’t appear on American supermarket shelves for another decade.

Toast satisfies us in a way that ordinary bread, as wonderful as it is, simply can’t quite compete with. But why, and — perhaps even more importantly — how do you make the ultimate slice of toast?

The answer starts with what is known as the Maillard reaction: a kind of carbohydrate-based alchemy. Essentially, a multitude of flavour compounds are created in the chemical reaction that occurs when your own amino acids and the sugar contained in toast collide. These compounds break down and multiply until furanones come into being — another type of compound that emits a slightly charred, sweet smell not dissimilar to maple syrup or burnt sugar. These are both classic, subtle taste undertones in that perfect slice of toast.

The questions don’t end there, however. Length of toasting time and ideal colouration of the slice need to be considered before we even think about adding butter.

Breadmaker Vogel did the hard yards by making a laboratory team crunch through 2,000 slices of toast in the name of research, back in 2011. The conclusions stated that the perfect toast required 216 seconds inside a pop-up set at five on a typical toaster dial. This, they claim, should assure the optimum builder’s-tea colour of the toast, as well as the perfect taste, reached only when the surface is 12 times crunchier than the centre.

A pale, seeded loaf was considered to be the ideal type of bread, but only if the butter is applied immediately after the toast pops up. Dilly-dallying as you put the kettle on can result in the vital heat that helps the butter melt upon first impact being lost.

Sometimes, that tub of butter isn’t enough. Many now worship at the altar of smashed avocado on artisanal sourdough, but we’ve long been happy to experiment with pouring, spreading, mashing or laying almost every conceivable food stuff on a toasted base.

The Victorians were partial to nibbling a post-dinner slice of toast groaning with anchovies, cheese and ham. In the Middle Ages, a common form of sustenance was ‘pokerounce’ or toast topped with hot honey, ginger and cinnamon.

There is a deeply personal, as well as a social, history to toast. More than merely an easy-fix snack, toast is nostalgic; a crunchy portal to a time in our childhood just before we learnt to use cutlery, but shortly after we first began to understand the difference between food eaten for pleasure and food eaten purely for survival.

Perhaps it’s not surprising, then, that the greatest ever description of toast and the wellbeing it induces comes from children’s literature. Kenneth Grahame’s Mr Toad is a great lover of toast and, if you can read the following passage without making a hasty rush for the bread bin, you’re built of stronger stuff than most:

‘When the girl returned, some hours later, she carried a tray… and a plate piled up with very hot buttered toast, cut thick, very brown on both sides, with the butter running through the holes in it in great golden drops, like honey from the honeycomb.‘The smell of that buttered toast simply talked to Toad, and with no uncertain voice; talked of warm kitchens, of breakfasts on bright frosty mornings, of cosy parlour firesides on winter evenings, when one’s ramble was over and slippered feet were propped on the fender; of the purring of contented cats, and the twitter of sleepy canaries.’

Celebrating toast: The best ways to eat toast

Leslie Geddes-Brown quizzes foodies for their ultimate ways to eat that most British of snacks: toast

Credit: Alamy

In praise of Fish and Chips, the ultimate British dish – and our pick of places to try it

10 reasons why the Full English Breakfast is one of the world’s great meals

Famous the world over, the ‘full English’ breakfast is making a comeback, finds Ellie Hughes, as she tucks into a

Rob is a writer, broadcaster and playwright who lives in Brixton, South London. He regularly contributes to publications including the Daily Mail, Daily Telegraph and Conde Nast Traveller. Rob is the Special Correspondent for the BBC Radio Four programme Feedback and can also be heard on the From Our Own Correspondent programme on BBC Radio Four and the World Service. His first play, 'The Gaffer', premiered at the Underbelly Theatre as part of the Edinburgh Fringe in 2023.

-

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabinQatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin has been setting the standard for Business Class travel since it was introduced in 2017.

By Rosie Paterson

-

Six of the best Clematis montanas that every garden needs

Six of the best Clematis montanas that every garden needsClematis montana is easy to grow and look after, and is considered by some to be 'the most graceful and floriferous of all'.

By Charles Quest-Ritson

-

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?As April 1 looms, Martin Fone tells the tale of one of the finest stunts ever pulled off.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade when there are more than 400 other varieties available worldwide? And do they really make the best preserve? Jane Wheatley investigates.

By Jane Wheatley

-

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this day

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this dayOnce packed with meat, such as ox tongue and mutton, alongside dried and candied fruit and extravagant spices, the mince pie is not what it once was — and food historian Neil Buttery says that's made them worse.

By Neil Buttery

-

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?Margarine has been a staple of our breakfast tables for over a century, but it hasn't always had a smooth ride — particularly from the dairy industry, who managed to impose a most bizarre sanction on their easily-spreadable, industrially mass-produced rival. Martin Fone explains.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?With the UK wine industry booming, Martin Fone takes a look at its history.

By Martin Fone

-

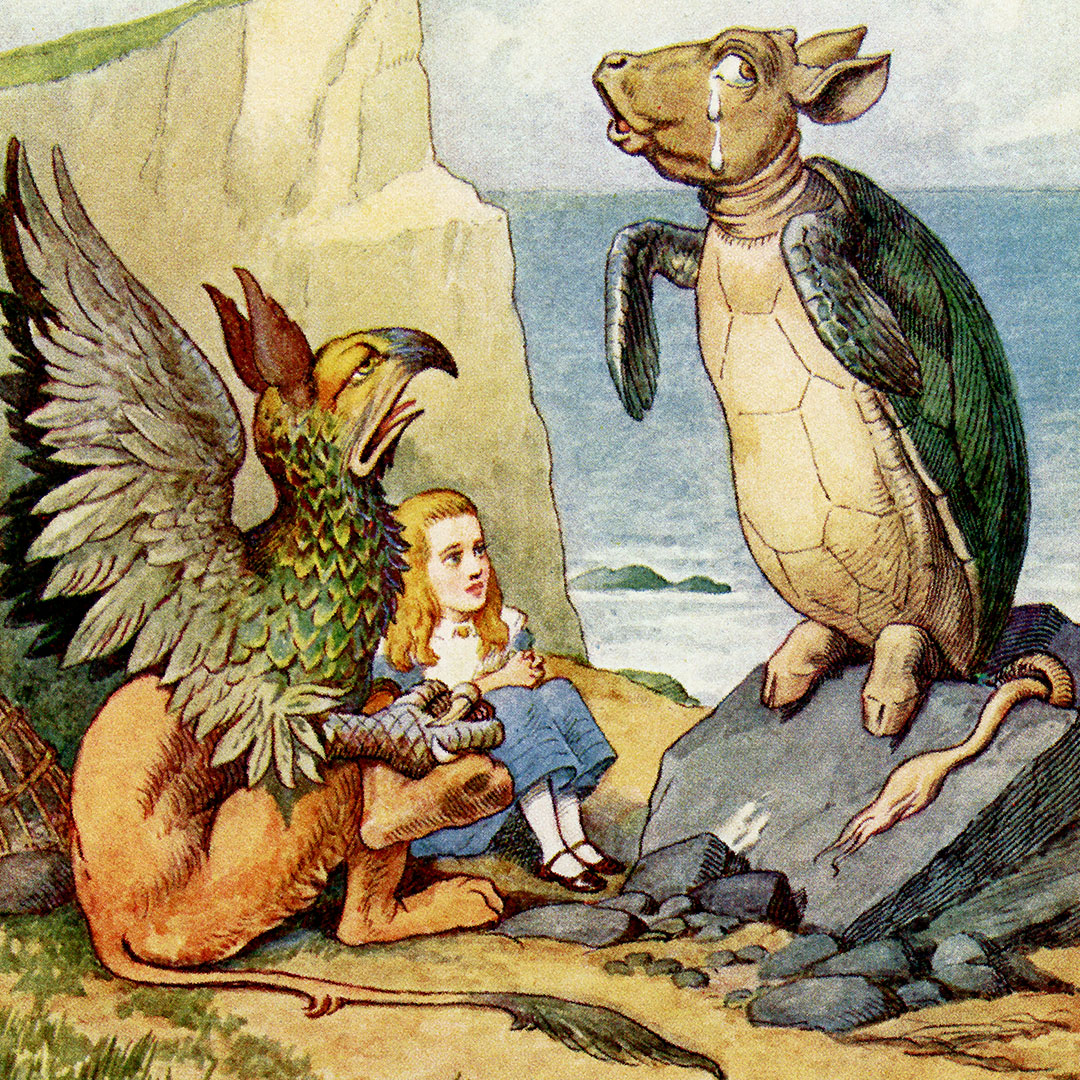

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?Martin Fone delves into the curious tale of an iconic Victorian delicacy: mock turtle soup.

By Martin Fone

-

A game of two halves — how the sandwich went from humble fare to a country-wide lunchtime obsession

A game of two halves — how the sandwich went from humble fare to a country-wide lunchtime obsessionWhat started life as a way to eat and play cards at the same time (so the story goes) is now the lunch of choice for the working world.

By Emma Hughes

-

Where to find the world's best club sandwich — and the story of this triple-layered paean to poolside delight

Where to find the world's best club sandwich — and the story of this triple-layered paean to poolside delightThe club sandwich, arguably the most famous of all sarnies, is a poolside staple, but its origins are tricky to trace, says Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker-Bowles