Curious Questions: How did a Swedish lighthouse genius and the 'father of advertising' make the Aga a country house must-have?

No English country house is complete, or so it sometimes seems, without an Aga at the heart of the kitchen — yet it's a Swedish invention whose roots are rooted in a tragic explosion, as Martin Fone discovers.

Housed inside Stenstorp’s beautiful Court House, the Dalén Museum has, since 1996, celebrated the life of one of Sweden’s greatest inventors, Nils Gustav Dalén (1869 – 1937). His finest achievement while Managing Director of Svenska Aktiebolaget Gasaccumulator — a company you’ll know better as AGA —was to improve lighthouse technology.

AGA, which specialised in the manufacture and distribution of acetylene gas, was one of several companies in the early twentieth century looking at using it to fuel lighthouse beacons. The problem was that a prodigious amount of the highly explosive gas was needed to produce a light of sufficient quality, making it an expensive and impractical option.

The Dalén Flasher was an ingenious solution, converting the gas into bubbles which were ignited by a perpetual flame. At a stroke, he had reduced acetylene consumption by an astonishing 90%, but the light shone all the time. To counteract this, Dalén designed the sun valve, a rod which expanded during daylight to cover a valve, extinguishing the flow of gas, and retracted once the light dimmed, allowing the beacon to flash once more. He also came up with Agamassen, a block containing cement, coal, and asbestos which absorbed acetylene so that it could be easily moved. These three inventions meant that lighthouses could now be automated.

1912 was a year of triumph and profound personal tragedy for Dalén. AGA were awarded the contract to fit his technology into the 35 lighthouses installed along the newly constructed Panama Canal. In November he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics ‘for his invention of automatic regulators for use in conjunction with gas accumulators for illuminating lighthouses and buoys’.

In September, though, while testing how much pressure a heated gas cylinder could withstand, something went wrong. It suddenly exploded, severely injuring and blinding Dalén as he went over to see what the matter was. His brother had to attend the Nobel Prize ceremony on his behalf.

Undaunted, Dalén carried on as Managing Director of AGA and as an inventor, amassing some 99 patents during his career. His enforced convalescence made him appreciate how much time his wife spent maintaining and using their old-fashioned cooking range. He decided to create a cooker that was cleaner, more economical, and easier to use.

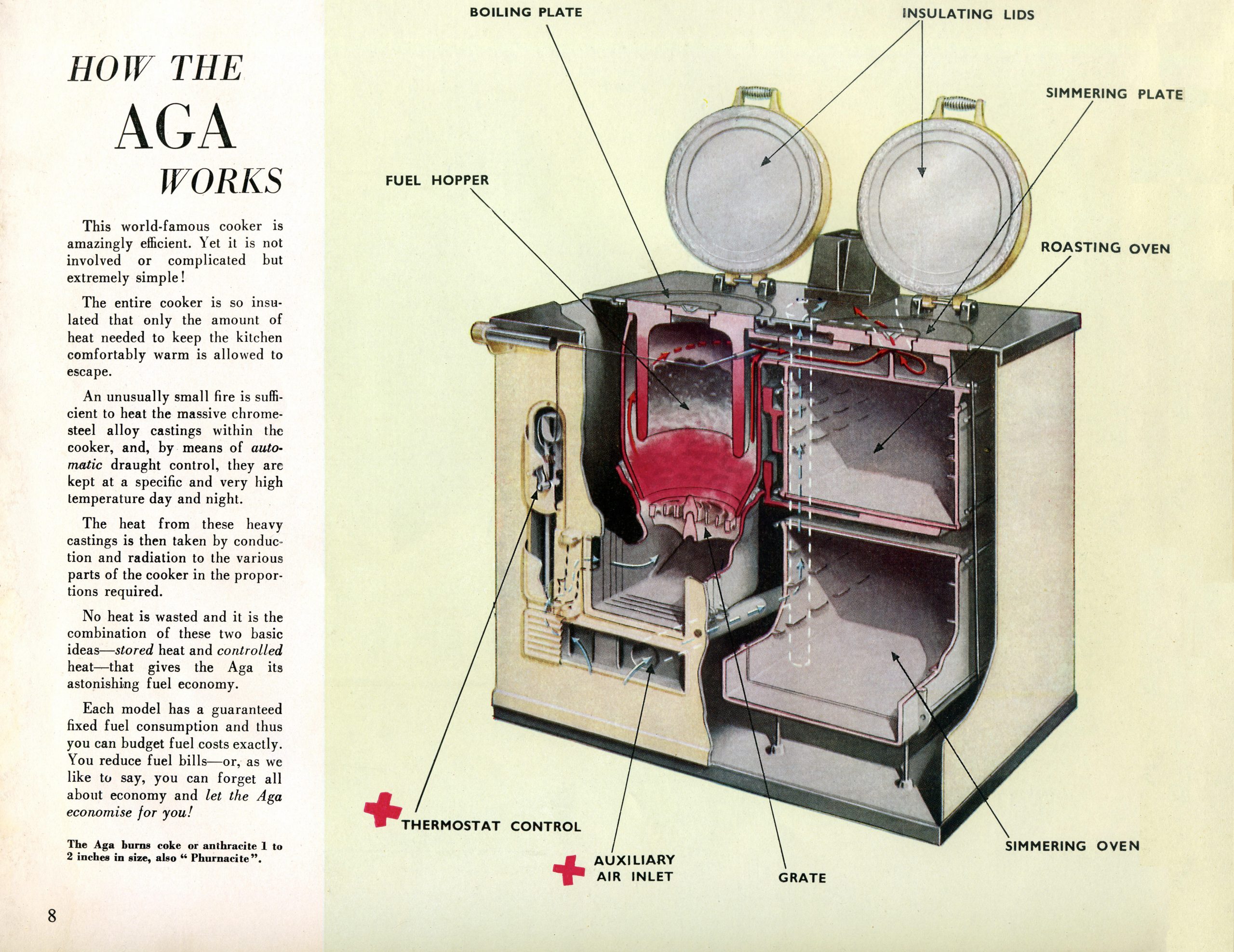

What Dalén had developed and patented in 1922 was a cooker with a single, internal heating unit, a fire brick heated by a naked flame fuelled by coal, which stayed on all the time, a variation on the idea he had used to good effect in the Flasher. Housed inside a cast-iron body which allowed heat to be stored efficiently, it transmitted consistent and yet varied temperatures to its two large hotplates and two ovens, relying on the radiant heat it produced rather than the manual regulation of temperatures by controls and knobs to cook food for long periods without burning or drying it out.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The AGA cooker first arrived in Britain in 1929 and its popularity grew steadily during the 1930s with 322 bought in 1931 and 1,705 in 1932, thanks in no part to the advertising genius and salesmanship of one of AGA’s door-to-door salesmen, David Ogilvy. The ‘father of advertising’ even penned what Fortune magazine described as ‘the finest instruction manual ever written’, The Theory and Practice of Selling an AGA Cooker (1935).

Salesmen, Ogilvy advised, should ‘dress quietly and shave well’ and on no account wear a bowler hat. The AGA, he noted, offered the new owner the prospect of ‘fuel savings, staff reduction, reduced expenditure on cleaning materials… abolition of chimney sweeps; painting and redecorating is unheard of, electric irons and their antics are unnecessary; raids on registry offices for new servants become a thing of the past’. For the smaller house ‘some of its advantages are heaven-sent’, he enthused. ‘The AGA is a great boon to the “owner cook”. It is in fact her maid’.

The AGA was an aspirational product, and there was a certain cachet and, dare one say, smugness in owning one, a feeling that persists, Mary Berry once saying that owning one was ‘like joining the best club in the country…when you meet another AGA owner it is like discovering another friend.

A version of the cooker adapted for the British market was manufactured at AGA Heat Ltd’s factory in Smethwick from 1932. During the Second World War the British Government installed AGAs into munitions works, communal feeding centres, and hospitals to facilitate mass catering. Such was the wait for cookers — 27 weeks at one point — that a second manufacturing site, in Coalbrookdale in Shropshire, was opened in 1947. Sales boomed in the 1950s to around 50,000 units per annum, fuelled by the introduction of new ranges and colour palettes, moving away from the obligatory cream in 1956.

Slowly AGA cookers embraced more efficient and convenient energy sources, using oil from 1964, gas from 1968, and electricity from 1985, and even came to terms with the technological revolution of the 21st century. Most cookers sold today are controlled by an app, allowing the owner to set the time when the cooker needs to reach optimal temperature and when to power down and go into sleep mode. On some newer models the ovens and hotplates can be individually controlled and switched on and off independently.

Nevertheless, a hundred years after Dalén received his patent, some issues surrounding AGA cookers have come to the boil. Well-crafted using high quality materials, AGAs have an average lifespan of forty years, which means that many have a significantly larger carbon footprint than other cookers. A large, old-style coal-fired AGA produces nine tonnes of carbon dioxide a year, 35% more CO2 than the average UK house produces. Even their most passionate advocates concede they are not the most environmentally friendly.

Before the recent hike in energy prices with the promise of more to come, a survey of AGA owners in 2020 revealed that their principal dislike was the cost of running their cookers. The AGA website suggests that for their newer electric ranges, running costs can be anywhere between £30 and £40 a week, an estimate that soon may be viewed as undercooked.

A recent report in Bloomberg UK suggested that the business of removing AGAs was booming, while on a Facebook group, I love my Aga!, members are now sharing advice on how to save energy while running the appliance.

As Ogilvy presciently observed in 1935, though, AGAnomics is more nuanced than that. Instead of saving on chimney sweeps and servants, modern AGA owners will point out that their cooker’s versality eliminates the need for other kitchen paraphernalia such as kettles, toasters, microwaves, radiators, and airing cupboards. It is sure to be a topic of heated debate in households where the budget is under strain.

Perhaps the AGA’s greatest challenge as it moves into its second century is to demonstrate its relevance to changing tastes in foods and cooking styles. Ideal for cooking more traditional, wholesome British foods, it is less adept at handling dishes comprising several elements that require a precision of timing to pull together. It is unlikely to make an appearance on Masterchef. But whatever their future, AGAs, like flat-pack furniture, are testament to the impact of Swedish design on the British household.

Mary Berry: ‘Why I love my Aga’

Julie Harding lifts the hot plate on the heart-warming kitchen feature no country house should be without.

Credit: Farlap / Alamy

Farming Life: The cock on the brink of death, saved by spending a night in the Aga

The chickens are reprieved and it’s keep calm and carry on with the calving, says our resident farming columnist Jamie

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to last

Designer's Room: A solid oak French kitchen that's been cleverly engineered to lastKitchen and joinery specialist Artichoke had several clever tricks to deal with the fact that natural wood expands and contracts.

By Amelia Thorpe

-

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025

Chocolate eggs, bunnies and the Resurrection: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 18, 2025Friday's quiz is an Easter special.

By James Fisher

-

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?As April 1 looms, Martin Fone tells the tale of one of the finest stunts ever pulled off.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade when there are more than 400 other varieties available worldwide? And do they really make the best preserve? Jane Wheatley investigates.

By Jane Wheatley

-

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this day

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this dayOnce packed with meat, such as ox tongue and mutton, alongside dried and candied fruit and extravagant spices, the mince pie is not what it once was — and food historian Neil Buttery says that's made them worse.

By Neil Buttery

-

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?Margarine has been a staple of our breakfast tables for over a century, but it hasn't always had a smooth ride — particularly from the dairy industry, who managed to impose a most bizarre sanction on their easily-spreadable, industrially mass-produced rival. Martin Fone explains.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?With the UK wine industry booming, Martin Fone takes a look at its history.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?Martin Fone delves into the curious tale of an iconic Victorian delicacy: mock turtle soup.

By Martin Fone

-

A game of two halves — how the sandwich went from humble fare to a country-wide lunchtime obsession

A game of two halves — how the sandwich went from humble fare to a country-wide lunchtime obsessionWhat started life as a way to eat and play cards at the same time (so the story goes) is now the lunch of choice for the working world.

By Emma Hughes

-

Where to find the world's best club sandwich — and the story of this triple-layered paean to poolside delight

Where to find the world's best club sandwich — and the story of this triple-layered paean to poolside delightThe club sandwich, arguably the most famous of all sarnies, is a poolside staple, but its origins are tricky to trace, says Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker-Bowles