Curious Questions: How, and why, do people eat stinging nettles?

Every summer, people from around the world gather at a pub in Devon for the World Nettle Eating Championship. But why? And how? Ian Morton takes a look, and delves into the strange history of this viciously-stinging yet ubiquitous plant.

It went by many names, but whether the locals called it scaddie, heg-beg, hiddgy-piddgy or hoky-poky, they avoided needless contact. In some parts, it was referred to as the naughty man’s plaything — quaint, but the ‘naughty man’ was the Devil himself and a ‘plaything’ was essentially a source of cruel sport and entertainment. In this case, the Devil was assumed to derive amusement from the discomfort wrought by the stinging nettle, considered his realm because, according to folklore, it grew wherever he and his angels fell when they were tumbled out of Heaven. A comprehensive fall from grace, it seems, as some 40 species and sub-species of nettle sprang up on any and every moist and temperate northern landmass.

None is more potent and prolific than our European nettle (Urtica dioica), also called the Devil’s plant, the Devil’s leaf, the burn weed, burn hazel, tanging nettle and bull nettle, all of them minatory.

Nettle leaves sting because they are covered in tiny hollow filaments, the silica tips of which break off at the lightest touch to expose sharp points that deliver an instant shot of formic acid into the skin surface, followed by histamine, acetylcholine and serotonin.

Strange, then, that throughout recorded history Man has managed to derive much good from the nettle, despite its satanic chemistry. Hostile to the touch, it has nonetheless been cherished down the ages as a source of food, drink, cloth and medical treatment. The naughty man, it seems, has been a victim of the law of unintended consequences.

From the Stone Age, our ancestors dined on nettles and brewed nettle beverages, and rural folk down the centuries have supplemented their diet with young shoots freely foraged in field, hedgerow and woodland.

Nettle as a food constituent was not totally confined to the countryside, either. Samuel Pepys recorded that on Monday, February 25, 1661, visiting a friend’s house in London, ‘there did we eat some nettle porridge, which was made today... and it was very good’. Isabella Beeton recommended nettles for soup when in season (January–February and April–September) and today’s rural cookbooks abound with recipes.

Young nettle leaves blanched to draw their sting may serve as an alternative to spinach or chard, and dieticians recognise that cooked nettle leaves contain vitamins A and C, iron, potassium, manganese and calcium, with those gathered in peak spring and summer condition boasting 25% protein.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Nettles make modest contributions to some foods even today, wrapping Cornish Yarg cheese, for example, and figuring in green Italian tortellini. Furthermore, nettle dust added to chicken feed apparently makes the yolks a deeper yellow. Traditional nettle tea, beer, soup and bread are offered locally by a few dedicated participants during Be Nice To Nettles week in May.

Yet all such use of nettles in food pales by comparison to the infamous World Nettle Eating Championship, held annually in June at the 16th-century Bottle Inn at Marshwood in Dorset.

According to local folklore the contest began in 1986 with a row between two farmers over whose land produced the tallest nettles. One of them, a man named Alex Williams, was so adamant that his were bigger that he promised to eat any nettle longer than his — and thus the competition began.

The event currently takes place alongside a charity beer festival at the pub, with each contestant served up 2ft lengths of nettle stalk from which they must pluck and eat the leaves. More stalks are provided as needed, and the winner is the man or woman who, at the end of an hour, has more bare nettle stalks than anyone else. Contestants are allowed — even encouraged — to dip the nettle leaves in beer or water, but hands and mouths do get exactly as covered in stings as you might imagine.

The record, held by a Devon chef called Phil Thorne, is 52 stalks. That’s 104ft of raw nettles eaten in an hour.

It’s hardly surprising that people have tried eating nettles considering how well they have worked in folk remedies. Indeed, over the centuries the nettle’s most widespread contribution to the human condition has been medicinal. The fifth-century BC ‘father of western medicine’, Hippocrates, whose ethical oath is traditionally sworn by physicians, listed 61 complaints and disorders that could be treated with nettles. Pliny endorsed his conclusions. The Celts drank nettle beer for rheumatism and Roman invaders unused to northern climes beat their aching joints with nettles.

Herbalist and folk remedies may have been marginalised, but medical science supports the value of nettle extracts in creams, soaps and shampoos in alleviating a wide variety of conditions, ranging through hay fever, prostate enlargement, Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis, gout, haemorrhoids, arthritis, sciatica, gingivitis, oily scalp, dandruff and the prevention of baldness.

Add anaemia, high blood pressure, excessive blood sugar, plus the claim that side effects are fewer than with prescription drugs, and nettle preparations appear something of a panacea — and one of the deities invoked in the original Hippocratic oath was Panacea, the Greek goddess of Universal Remedy.

Beyond even that, however, the ancient Chinese were making paper from them 5,000 years ago and Mediterranean cultures 2,000 years ago, although Egypt preferred papyrus, thus giving us the word paper. Green dyes from the leaves and stalks and yellow from the roots have a long history, especially in Russia. Twine made from nettle fibre has been dated at Neolithic sites and nettle fabric was found wrapped around cremated bones in a late Bronze Age grave at Voldtofte in Denmark.

In Britain, despite the introduction of flax by Phoenician traders in about 900BC, the nettle remained a readily harvested alternative to linen and wool, its fibres spun on domestic wheels and woven on cottage looms. It even reached the best bedrooms. Good Queen Bess is said to have slept under a nettle-cloth coverlet.

Eighteenth-century Scottish poet Thomas Campbell wrote not only of how he ate nettles, but also slept in nettle sheets and dined off nettle tablecloths, the fabric being more durable than linen. After cotton appeared in Europe and steadily progressed as the dominant lightweight material, the command exercised by the British Navy over the cotton-trade routes was so strong that Continental enemies resorted to nettle fabric. Napoleon’s soldiers wore nettle-cloth uniforms and German forces during the First World War were supplied with nettle rucksacks, strapping, sandbags, uniforms and shirts, although it took 100lb of nettles to produce one shirt.

This expedient provoked a breeding programme set up in 1927 by Prof Gustav Bredemann of Hamburg University, which produced 27 cloned varieties with higher fibre content than wild nettles. Although research ceased in 1950, its results were revisited in the 1990s and Germany, Austria and Italy joined an EU-funded project to re-examine nettle viability. Dutch fabric firm Brennels produced fabric from 2006, but ceased in 2013; Swiss company SwicoFil supplies material to German clothing manufacturers and some Continental houses have offered nettle fashions. The nettle variety Ramie has long been used for fine fabric in China and Japan.

Key features of nettle fibre include its flexibility and its hollow stem structure with vascular tissues of xylem vessels, strong lignin-laced sclerenchyma fibres and organic polymers, which keep the plant sturdy. Tightly spun, it is suitable for summer clothing, but lightly twisted it retains air to create natural insulation for winter wear.

Nonetheless, nettle’s impact on the clothing scene has been limited. Environmentalists grieve, because the plants need little water, no fertilisers or pesticides and grow enthusiastically in poor soil, so their eco-damage is negligible compared with cotton or synthetics. These, however, are too established, cheap and easily worked to be economically challenged.

De Montfort University in Leicester pursued a 2004 Defra-supported STING project (Sustainable Technologies In Nettle Growing) as part of research into bast (vegetable-fibre) technology, but the programme of propagation, sowing and harvesting foundered after a few years.

A report declared that furnishing and fashion fabrics and horse feed offered commercial potential and advised that nettle production can be more profitable than conventional arable farming in the long term on marginal land. Southern and eastern Scotland were deemed well-suited and cultivation was claimed to present a significant opportunity for growers, spinners, weavers and fabric end-users, with further research recommended. Yet no outcome is evident.

Literature has not ignored the nettle. Chaucer recorded the traditional notion that the dock leaf eases its sting, as Shakespeare had Hotspur equate the nettle with danger, and interwove the plant in garlands around the brows of deranged Lear and drowned Ophelia. Hans Christian Andersen’s The Wild Swans featured a heroine who braved the stings to gather, spin and knit nettle coats to save her bewitched brothers.

Poet Edward Thomas, killed at Arras in 1917, applauded the symbolism of the plant’s enshrouding rusty old implements left in farmyard corners, hiding abandonment and decay. During the Second World War, poet Vernon Scannell saw uncompromising battlefield parallels, a nettle patch a ‘regiment of spite’ where ‘recruits’ appeared within a fortnight after he had slashed it flat with his billhook.

Nettles also have a positive countryside role. Naturalists approve because they offer an undisturbed haven for some 40 insect species and provide exclusive food for the caterpillars of the small tortoiseshell and peacock butter-flies, as well as the larvae of a dozen moths. Farmers are urged to leave nettles in field corners and along hedgerows.

Archaeologists also appreciate nettles, as they are suited to damp and derelict areas and thrive on previously occupied sites, clumps often betraying lost sites where human and animal occupation left phosphates and nitrogen in the soil. This possibly explains a traditional belief in the Highlands and Western Isles that nettles grow from the bodies of the dead.

More nettle facts

- The surname Nettles, a ‘habitational’ reference reflecting the presence of the plant, was first recorded in the 15th century in connection with the Manor of Nettleton, near modern Dewsbury, West Yorkshire. The dwelling (remains are the Grade I-listed Thornhill Lees Hall) was in the same family from 1412 to 1655. There is a Nettles coat of arms.

- Nettle rash is known medically as urticaria. Some cultures, including warring North American tribes, would ‘urticate’, self-administering the sting to remain alert when awaiting trouble

- A dock leaf is the rural emollient for a nettle sting and may introduce a neutralising chemical, and nettles and docks fortuitously thrive close together, but rubbing achieves some relief anyway. Mud, saliva, onions and lemon juice are also recommended.

- In Germany and Holland, getting into trouble is equated with sitting in nettles. In the Baltic region, a saying that lightning never strikes a nettle signifies that bad things don’t happen to bad people.

- Norse folklore associated Thor with nettles and gave another god, Loki, a magical nettle fishing net. Tibetans believe their ancient sage Milarepa lived on nettle soup and eventually turned green.

- To Anglo-Saxons, the nettle — called wergula — was one of their nine sacred herbs, protecting against elf mischief.

- Traditional uses for nettle juice included curdling milk to produce Cheshire cheese, tightening the seams of leaky barrels and packing fruit to retain its freshness.

Ready, steady, SLOW! The wonderfully eccentric (and very British) world of competitive snail racing

Summer in the British countryside brings with it all sorts of unusual events and celebrations – and they don't get any

26 miles of wine and cheese: The madness of the Marathon du Medoc

It’s been dubbed ‘the world’s most idiotic marathon’: a 26-mile run through vineyards, fuelled by wine and cheese. Emma Hughes

-

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'

A mini estate in Kent that's so lovely it once featured in Simon Schama's 'History of Britain'The Paper Mill estate is a picture-postcard in the Garden of England.

By Penny Churchill

-

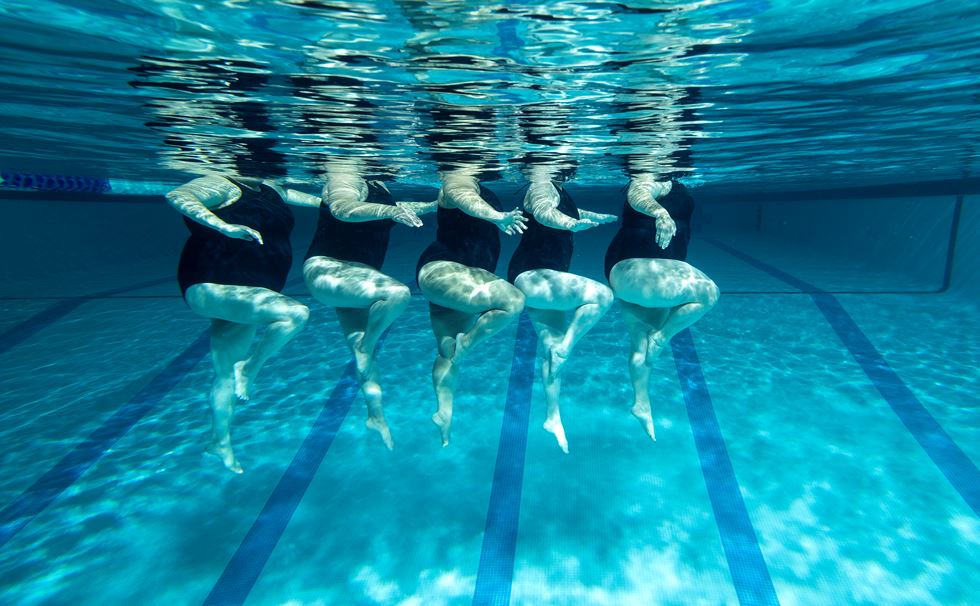

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead Heath

Splash! A Century of Swimming and Style: A whistle-stop history, from the Roman Baths to Hampstead HeathEmma Hughes dives into swimming's hidden depths at the Design Museum's exhibit in London.

By Emma Hughes

-

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?

Curious Questions: What is the greatest April Fool's prank ever played?As April 1 looms, Martin Fone tells the tale of one of the finest stunts ever pulled off.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?

Curious questions: Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade?Why do we use Seville oranges to make marmalade when there are more than 400 other varieties available worldwide? And do they really make the best preserve? Jane Wheatley investigates.

By Jane Wheatley

-

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this day

Mince pies really did once contain meat — and this Victorian recipe will convince you that they should to this dayOnce packed with meat, such as ox tongue and mutton, alongside dried and candied fruit and extravagant spices, the mince pie is not what it once was — and food historian Neil Buttery says that's made them worse.

By Neil Buttery

-

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?

Curious Questions: Margarine used to be pink — but why?Margarine has been a staple of our breakfast tables for over a century, but it hasn't always had a smooth ride — particularly from the dairy industry, who managed to impose a most bizarre sanction on their easily-spreadable, industrially mass-produced rival. Martin Fone explains.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?

Curious Questions: Wine has been made in Britain for over 1,000 years — so why have we only just turned it into an industry?With the UK wine industry booming, Martin Fone takes a look at its history.

By Martin Fone

-

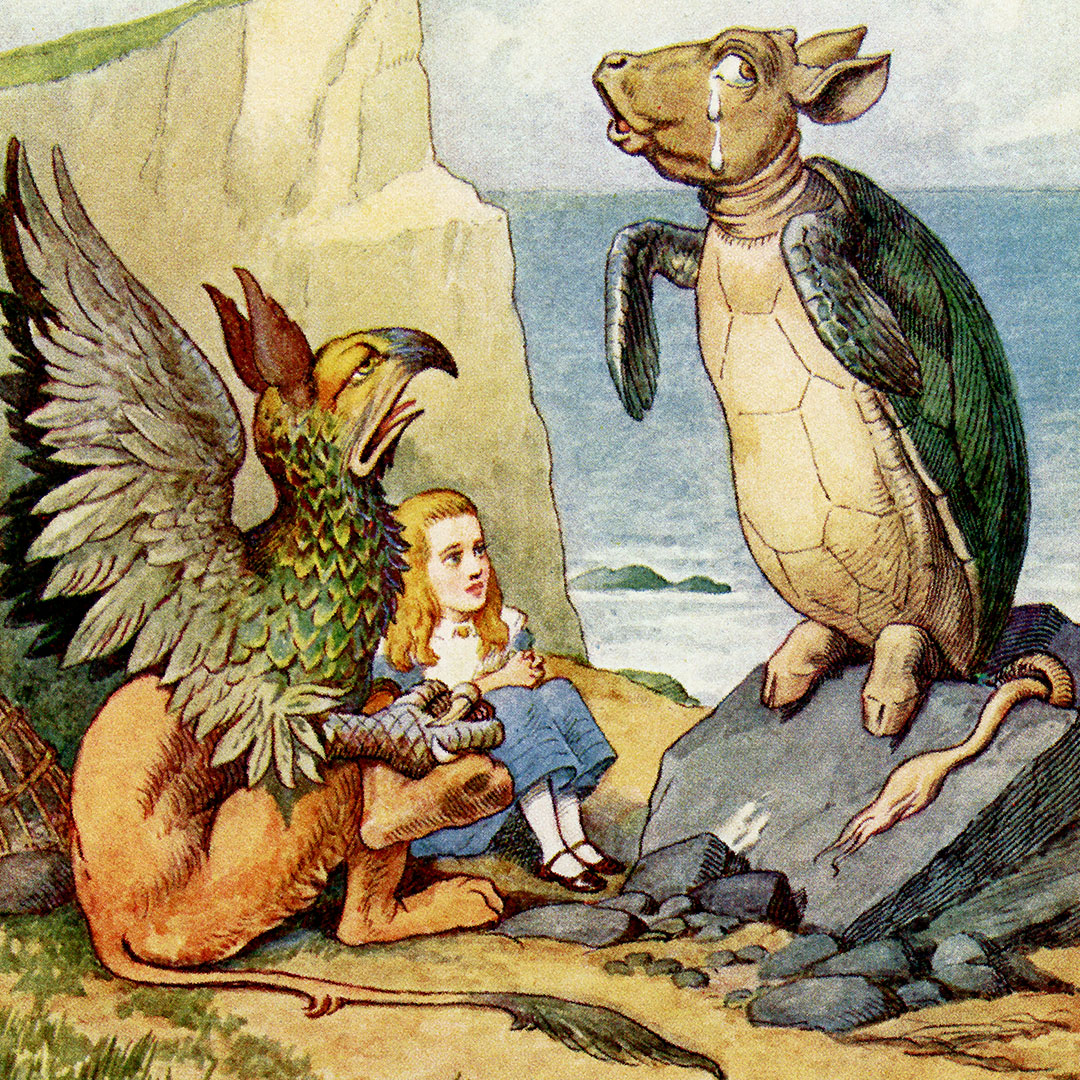

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?

Curious Questions: What is mock turtle soup? And did it come before or after 'Alice in Wonderland'?Martin Fone delves into the curious tale of an iconic Victorian delicacy: mock turtle soup.

By Martin Fone

-

A game of two halves — how the sandwich went from humble fare to a country-wide lunchtime obsession

A game of two halves — how the sandwich went from humble fare to a country-wide lunchtime obsessionWhat started life as a way to eat and play cards at the same time (so the story goes) is now the lunch of choice for the working world.

By Emma Hughes

-

Where to find the world's best club sandwich — and the story of this triple-layered paean to poolside delight

Where to find the world's best club sandwich — and the story of this triple-layered paean to poolside delightThe club sandwich, arguably the most famous of all sarnies, is a poolside staple, but its origins are tricky to trace, says Tom Parker Bowles.

By Tom Parker-Bowles