Curious Question: How did the Victoria Sponge get its name?

Our most beloved sponge cake carries a grandly regal name: the Victoria Sponge. But how did it come to be called that? Ahead of National Cake Day on November 26, Martin Fone investigates.

A nation of cake lovers, the British spend over £1.3 billion on them a year and, in 2018/19, consumed on average 151 grams of cakes, buns, and pastries per person per week. That's equivalent to three slices, in case you were wondering.

The enforced changes to our daily routines over the last two years are likely to have seen these figures rise. Such is our obsession with the soft, sweet foodstuff that it has spawned an unlikely televisual hit in The Great British Bake Off (GBBO), now in its twelfth season, after initially airing August 17, 2010.

Firmly established amongst the nation’s favourites is the Victoria sponge, or the Victoria sandwich cake, a two-layer, sponge-like, airy cake with a layer of jam and — for the indulgent — cream in the middle and a dusting of icing sugar on the top. The lodestone of the recipe is the weight of the eggs in their shells which determines the proportions of the butter, sugar, and flour to be used.

Deceptively simple as the recipe may be, it is a real art to make the perfect Victoria sponge, so much so that it is seen as the yardstick for judging a baker’s acumen. The Women’s Institute have elevated it to an art form, where marks can be gained or lost depending upon the texture of the cake and the type of jam. Following suit, the GBBO has made one of its supreme challenges the production of the perfect Victoria sponge, where contestants seek to avoid such faux pas as a soggy bottom. But how did it come by its name?

RECIPE: How to make Tommy Banks's elderflower drizzle cake

The origins of the sponge cake, so called because its texture is akin to that of the sea-dwelling sponge, can be traced back to at least the 15th century. At the court of the Duchy of Savoy, a confection like a sponge finger known as a Savoiardi — a low-density, dry, egg-based, sweet sponge cake biscuit shaped like a large digit — was produced to mark the visit of the French king. So tasty was it that it was adopted as the court’s official biscuit.

The earliest British recipe appeared in Gervase Markham’s The English Housewife (1615), although he called it biscuit bread. The ingredients included a pound of fine flour, a pound of sugar, eight eggs, four yolks, as well as half an ounce of aniseeds and a similar quantity of coriander seeds. Making it was not for the faint-hearted as Markham warned that 'will take very near an hour’s beating', to perfect the mixture.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

There is some controversy as to what the result looked like when it had been baked. Some commentators suggested that it would be very dense in texture, while others thought it would be more akin to a biscuit. One enterprising blogger went to the trouble of following the recipe and found that in texture it was slightly denser than a pound cake but with a similar sort of flavour. Perhaps that settles the argument, at least as far as the origins of the cake go. For now, though, to continue the story we need to take a look at another classic English sweet delicacy: custard.

Custard has a long culinary history, popular in the Middle Ages when baked in pastry, although, according to the 14th century collection of English recipes The Forme of Cury, it was also used as a binding for meat and fish. Elizabeth Bird was very partial to it, but one of its principal ingredients, eggs, upset her delicate digestive system. Fortunately, she was married to Alfred, a chemist who in 1837 had set up a shop underneath the old Market Hall in Birmingham’s Bull Street.

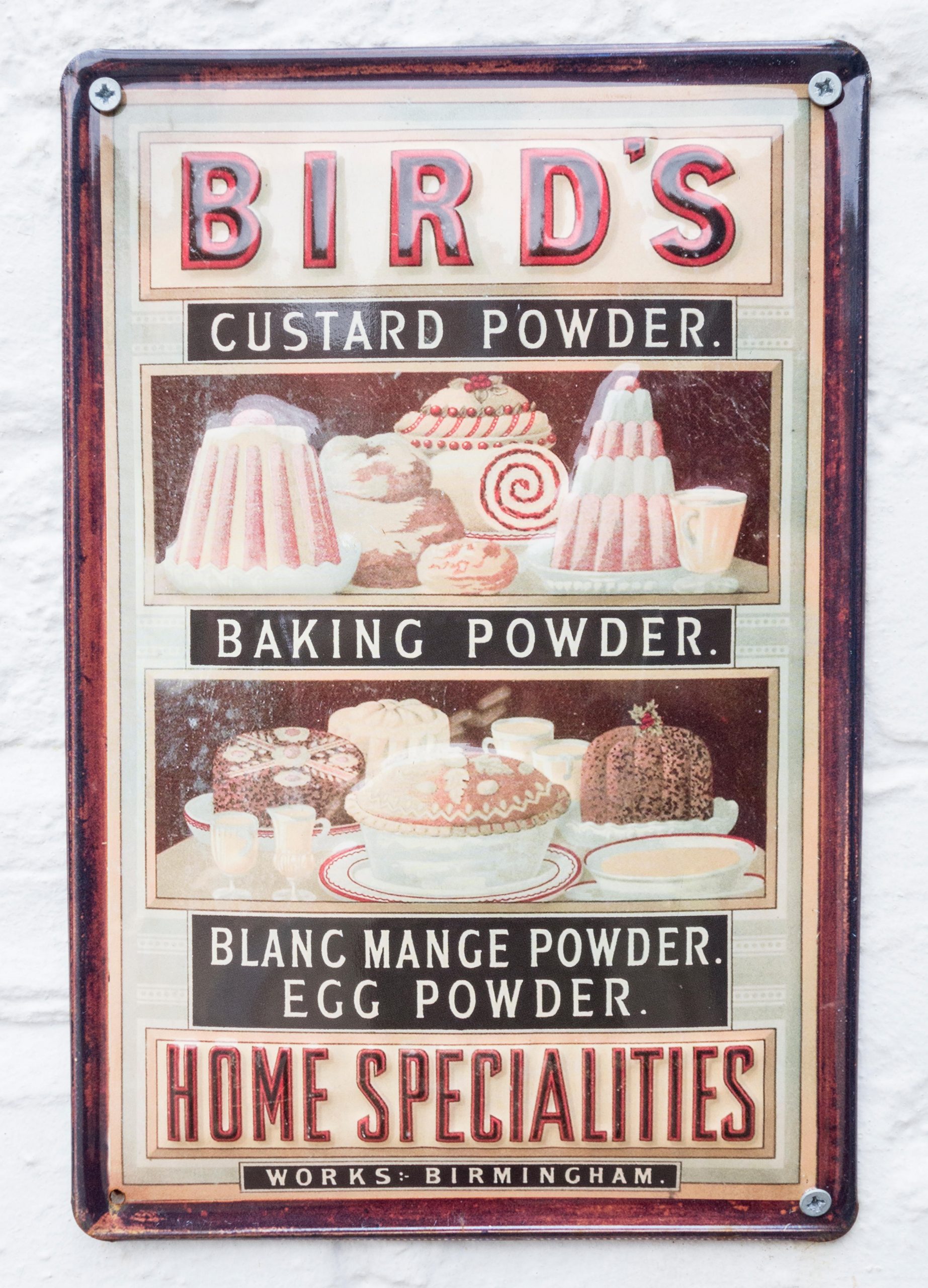

A dutiful husband, Alfred challenged himself to develop an egg-free custard, so that his wife could indulge her passion. He found, after many failed attempts, that adding cornflour to the milky mixture when warmed would thicken it sufficiently to give it a custard-like texture. This new form of custard was tried out at a dinner party and pronounced a success. Delighted with the feedback, Alfred set up a company in 1843, Alfred Bird and Sons, to produce his custard powder on a commercial basis. To this day his name is synonymous the world over with custard.

Elizabeth’s poor digestive system also reacted adversely to yeast. The indefatigable Alfred looked for a solution that would put bread and pastries back on the menu. He found that a mixture of a mild alkali in the form of bicarbonate of soda, and a mild acid, cream of tartar, combined with a filler to absorb moisture, such as cornflour, would, when moistened, produce carbon dioxide. The bubbles from the gas would cause the dough or cake mixture to expand and rise.

Alfred had invented what we know as baking powder, an effective substitute for yeast.

His timing could not have been better. In upper class circles luncheon had been introduced in the 18th century to fill the lengthening gap between breakfast and dinner, which was usually served anywhere between seven o’clock and eight-thirty in the evening. Luncheon, though, was normally a light affair, leaving many to endure a long afternoon without any form of refreshment. Anna Russell, the seventh Duchess of Bedford and Queen Victoria’s Lady of the Bedchamber between 1837 and 1841, hit upon an innovation that revolutionised the social world from the 1840s: the taking of afternoon tea.

By four o’clock each afternoon, the Duchess started to feel peckish and would ask her servants to bring a pot of tea and some cakes to her chamber. Finding that this combination filled the gap admirably, she extended invitations to some of her social circle to her rooms at Belvoir Castle at five o’clock to take afternoon tea. On her return to London Anna continued the practice, sending printed cards to her friends inviting them to take tea and a walk with her.

So popular did this novel form of breaking the fast between luncheon and dinner become that other society hostesses soon followed suit. One of whom was Queen Victoria, who, notorious for her very sweet tooth, had, by 1855, made it into a formal occasion by insisting that her ladies wore formal attire. Her table groaned with delicacies, but pride of place was reserved for a light and airy, perfectly risen sponge that was only possible thanks to Alfred Bird’s baking powder. So enamoured was she with the cake that following Albert’s death in 1861 it was named the Victoria sponge in her honour.

Its adoption by the middle classes was assured by its inclusion in Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861), although to the consternation of many an aspiring hostess Isabella’s recipe in her first edition omitted any reference to eggs.

Alfred’s ingenuity knew no bounds. He developed a formula for jelly powder and an egg-substitute and in 1859 built a water barometer. He also produced a set of harmonised glass bowls boasting a range of over five octaves which, his funeral notice observed, 'he played with much skill'. Although he did not patent his baking powder — allowing rivals to take a slice of the market and Henry Jones, a Bristol baker, to incorporate it in his self-raising flour — he did well from it in any case. Alfred’s estate was worth around £9,000 when he died on December 15, 1878.

Next time you take a slice of Victoria sponge, spare a thought for Elizabeth Bird’s delicate digestive system and her husband’s ingenuity.

The ultimate 'posh' rhubarb and custard? How to make rhubarb, raspberry and thyme mille-feuille

Here's how to elevate simple rhubarb and custard to something rather smart.

Credit: Melanie Johnson

Carrot, blood-orange and hazelnut cake with cream-cheese frosting

Carrot cake, but not as you know it.

Cherry, almond and chocolate drip cake with mini meringues

A pretty cherry cake, perfect for afternoon tea in the garden.

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.