Curious Questions: How did one of the world's great biscuits get named after a freedom fighter named Garibaldi?

Martin Fone delves into the curious history of the garibaldi biscuit — and how it's linked to the tale of Italian freedom fighter-turned folk hero Giuseppe Garibaldi.

In March 2016 Country Life ran a feature entitled Britain Takes The Biscuit. There lurking among some of my favourites was a confection consisting of a layer of currants squashed between two thin layers of biscuit dough.

Their distinctive look has earned them the nickname of fly sandwiches. More charitably, perhaps, they show what happens when an Eccles cake encounters a steam roller. In New Zealand they are known as Fruitli Golden Fruit, while Australians — who rarely beat around the bush — call them Full O’Fruit.

To find them in a British supermarket, though, you will have to search for the name Garibaldi. On the face of it, naming the biscuit after an Italian revolutionary may seem a surprising choice; but Garibaldi had a special place in the affections of the British public.

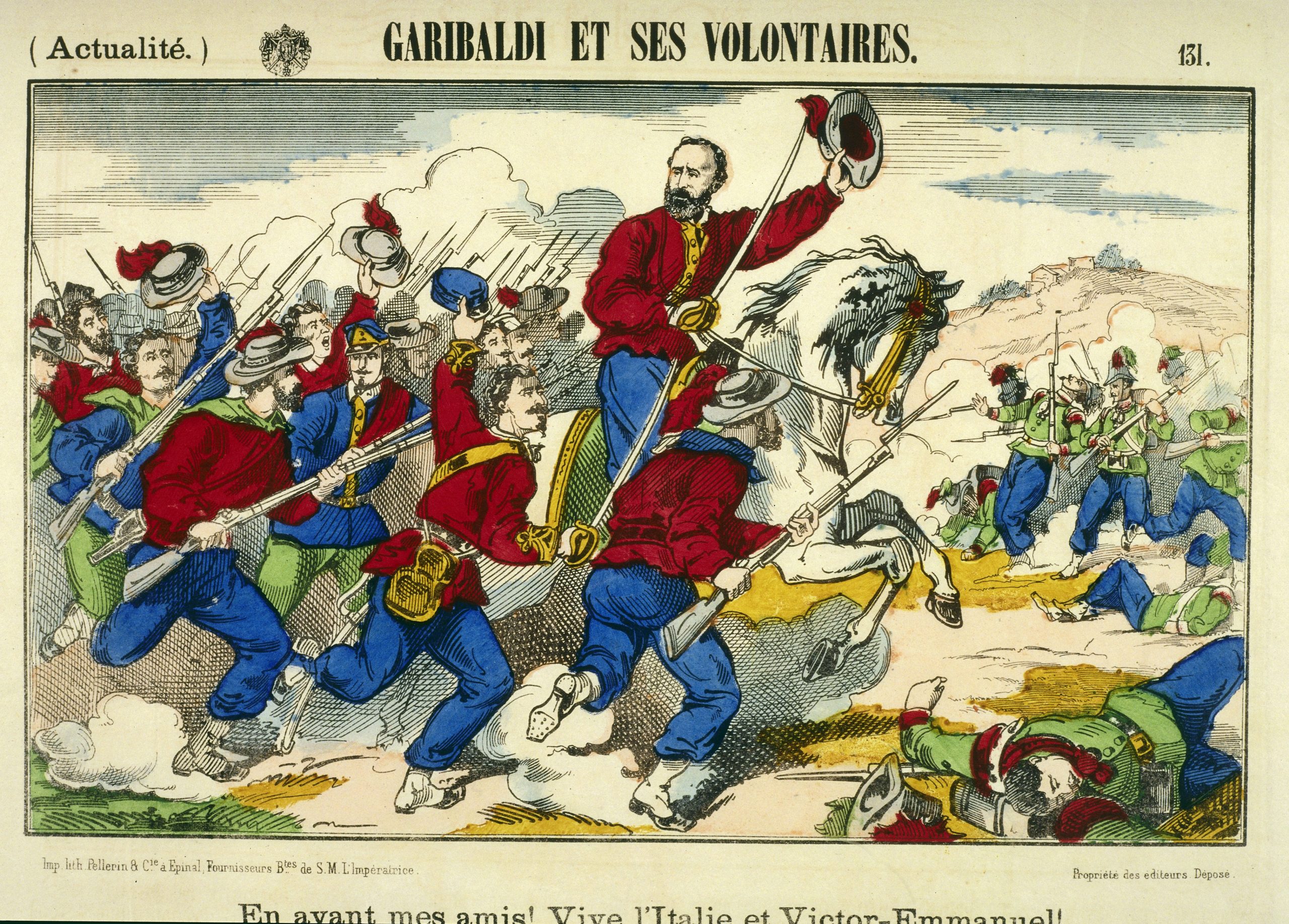

We have a rather curious attitude towards revolutionaries and leaders of popular uprisings. So long as they do no harm to our interests while weakening those of our opponents, we rather admire them. And there was a lot to admire about Giuseppe Garibaldi. With a band of a thousand poorly equipped, red-shirted men, he had conquered Sicily.

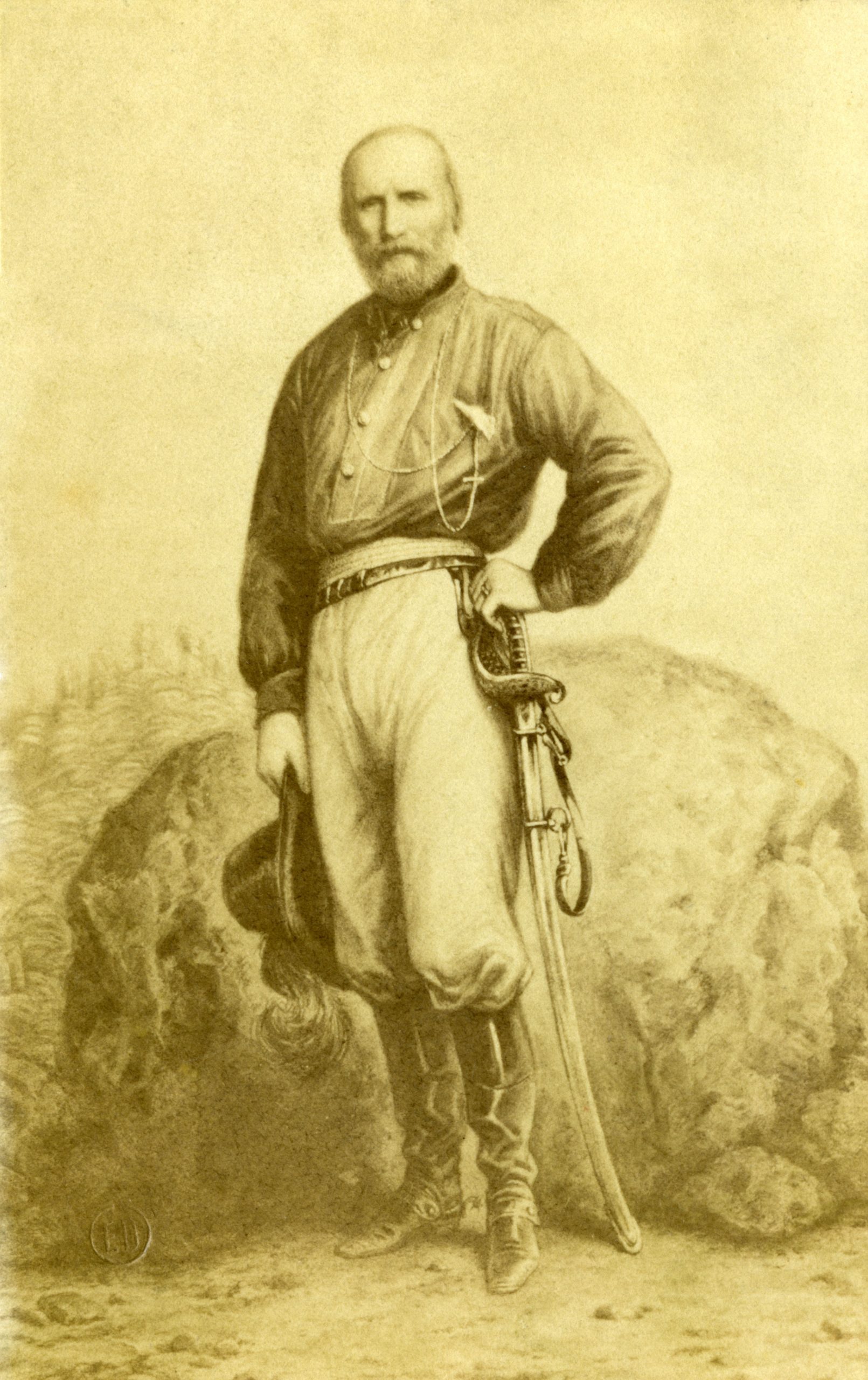

Moving on to the mainland, in what the tabloids would surely have dubbed the battle of the biscuits, he succeeded in liberating his people from the oppression of the Bourbons — the Spanish Bourbons, that is — and the Austrians, whose resistance finally crumbled at the siege of Gaeta in 1861. The Italian peninsula, which for centuries had been a hotchpotch of miniature kingdoms, republics and city states, was transformed into a single state by the Risorgimento, as the uprising was dubbed. Garibaldi, with flamboyant beard and distinctive red shirt, was the man who had turned a dream into reality.

Historians may quibble that this is an over sensationalised and romanticised version of events, as surely it is, but let’s not let the truth get in the way of a good story. Garibaldi had become an international star, the poster boy of the 1860s, dubbed the ‘Hero of the Two Worlds’ having tasted military success in South America as well as in Europe. After many years of frustration, disappointment, defeat, and exile, fame and glory were now his; everyone from Abraham Lincoln to Charles Dickens poured praise on him, and his fame endured into the 20th century as the great historian AJP Taylor dubbed him ‘the only wholly admirable figure in modern history’.

Earlier in his life, such an outcome seemed out of the question. Hounded out of Italy by the French and Piedmontese in 1849, Garibaldi went into exile in the United States, along the way making two of his three visits to England. The first was a low-key affair, landing in the port of Liverpool in June 1850 en route to New York, savouring the delights of the city for six days. On March 11, 1854, on his way back to his homeland on a ship called the SS Commonwealth, he stopped off in Tyneside.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

There he was enthusiastically greeted by the locals and hosted by the radical politician and newspaper proprietor, Joseph Cowen Junior. Garibaldi spent time meeting with local industrialists and politicians, discussing his plans and aspirations for the unification of an independent, republican Italy. To mark the Italian’s visit, Cowen organised a public subscription through his newspaper, the Evening Chronicle, readers being invited to donate one penny a head.

At a private party held on board the SS Commonwealth on April 11th, Garibaldi was presented with a golden sword and periscope. The sword bore an inscription: Presented to General Garibaldi by the People of Tyneside, Friends of European Freedom, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, April 1854. Quite what he made of the gesture is not recorded, but the following day he set sail for Genoa.

On his third visit, in 1864, Garibaldi was fêted as a superstar, the conquering hero, lionised by the great and the good as well as the hoi polloi, by radicals and conservatives alike. To the establishment he was someone who had blackened the eyes of Britain’s foes, whilst to the radicals and the working classes, fighting to establish some basic rights, he was a champion of the underdog.

Crowds flocked to see him as soon as his ship docked in Southampton. By the time he had got to London, Garibaldi-mania had swept the country. The Spectator, in its edition of April 16, 1864, gave the General’s visit front page treatment, reporting that on arriving in London, he ‘was welcomed by a concourse of people as large as that which witnessed the entrance of the Princess of Wales’. The crowds were so great that it took his carriage five hours to make the journey from Nine Elms Station to Stafford House in St James’s.

After ‘an entertainment, which was attended by the highest nobles in Great Britain’ on the following evening an event in his honour at the Opera House in Covent Garden ‘swarmed with Peers, and ladies rained flowers on the Liberator’s head as he bowed to the throng… and the people still crowd in masses to catch a glimpse of his face’.

Garibaldi found time to plant a tree in Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s garden, autographed many a visitor’s book and received numerous honorary awards. He made a speech at Crystal Palace which drew a crowd of 25,000. For those not lucky enough to see him, they could content themselves with some of the Garibaldi-themed memorabilia available, figurines, plaques, tankards, sheet music, and photographs. Streets and pubs were named after him.

In 1857 tea merchant, James Peek, and his brother-in-law, a miller called George Frean, had set up a biscuit business, Peek, Frean & Co, in Bermondsey, linking tea and biscuits for ever. Initially manufacturing ‘hard tack’ — a rather tasteless cracker made from flour, water, and salt — Frean was keen to expand and bring more innovative products to the market. In 1860 George persuaded his schoolfriend, Jonathan (John), a member of Scotland’s foremost biscuit making family, the Carrs, of water biscuit fame, to take a break and join the company, probably by offering more dough. Carr’s role was to work on new ideas and products.

By 1861 Carr had come up with a biscuit that can be fairly said to be one that commands a unique position in the biscuit world. With its dry, not overly sweet dough, a squashed currant filling and shiny glazed top it was clearly a step up from hard tack. It also bears hallmarks of Carr’s origins, the characteristic strip of five Garibaldi biscuits reminiscent of the way shortbread petticoat tails, Scotland’s signature confection, are presented. Carr’s biscuit, though, has two distinct advantages over shortbread; it is less crumbly, and a weight watcher’s delight, each slice containing between 35 and 40 calories.

As to its name, 1861 was the year when the deputies of the first Italian Parliament declared Victor Emmanuel king of a unified Italy, realising Garibaldi’s ambitions. Developed three years before his triumphant visit to London, the firm probably named their biscuit to commemorate the moment, cashing on the General’s international fame. When Garibaldi-mania swept the country three years later, the name could not have harmed its sales’ prospects.

The Italians have a different version of events. They claim that Garibaldi was so enamoured with the biscuit when he was in the country that its manufacturers simply named it after him. Either way, while the General’s exploits have faded into the mists of time, his name lives on in one of our favourite biscuits. Fame is a curious thing.

Britain takes the biscuit

We delve into Britain’s rich biscuit history to find out why we are so bonkers about these sweet treats.

A home that really takes the biscuit: Inside the McVitie's mansion

This beautiful mansion in Hertfordshire was once the family home of Britain's great biscuit dynasty.

Credit: Alamy Stock Photo

If only dogs could talk: Reading the minds of Britain's 11 most popular breeds, from Labradors to Westies

Do pooches really take on the characteristics of their so-called owners? Rupert Uloth spoke to some of Britain’s most popular

Credit: Renaissance London

The secret life of fireplaces, and the fascinating tales they tell about the houses which host them

Fireplaces have all manner of wonderful stories to tell, as Amelia Thorpe discovers.

10 iconic sporting trophies (and the intriguing tales behind them)

Everybody loves a good sporting battle, but, often, the silverware up for grabs has been through far tougher times than

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.