'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

An exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

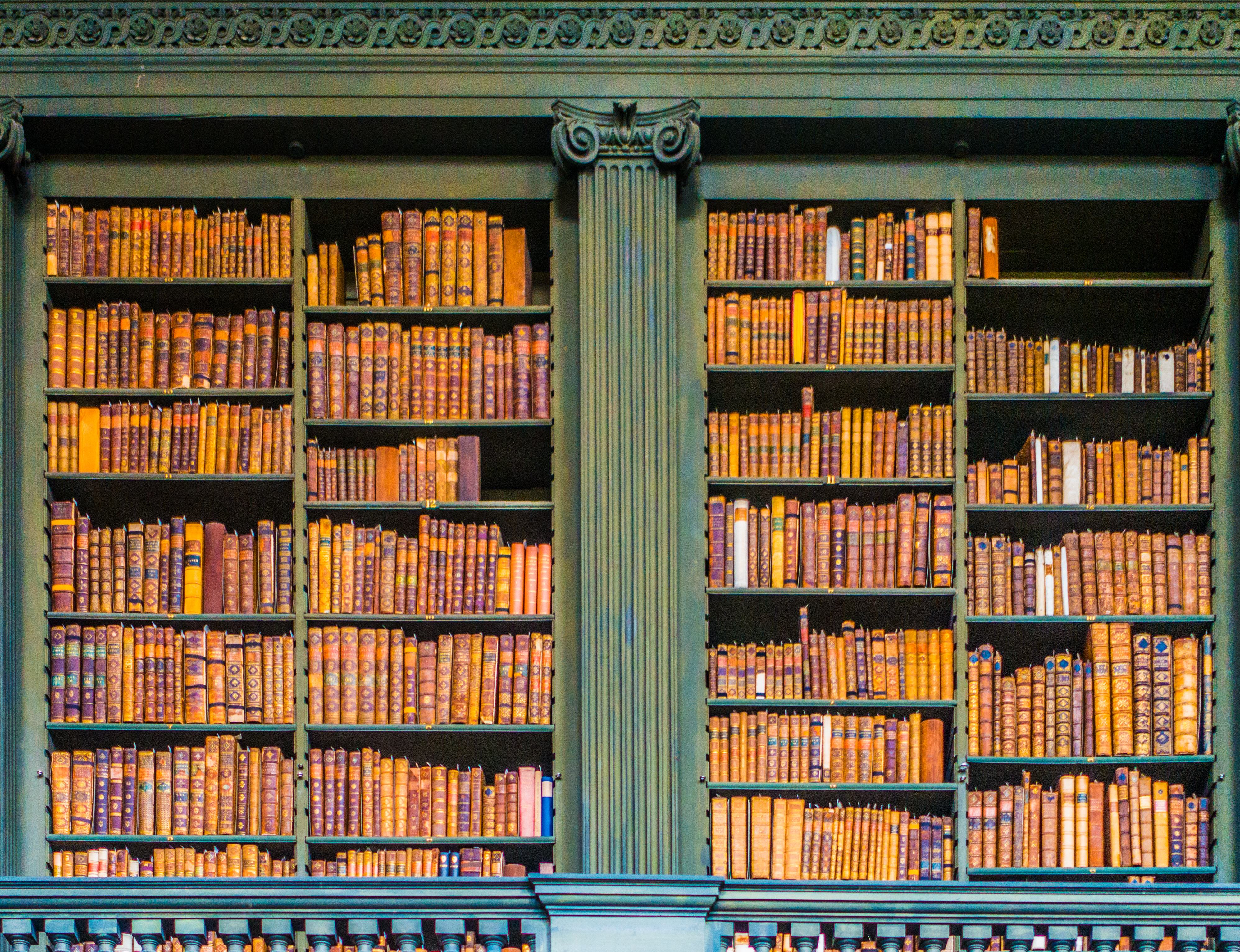

Understanding the history of any civilisation relies as much on the preservation of the past, as it does its documentation. Yet, in the United Kingdom, both popular and mainstream academic study of history places relatively little emphasis on the production of documents and texts, nor those who have dedicated their lives to putting them together for distribution, let alone the smaller number of specialists whose trade focuses on their long-term conservation and archiving.

Moreover, as the publishing industry continues to fixate on for-profit mass production, centred in warehouses and driven by industrial printing processes that are increasingly automated, the history of classic, manual bookbinding is often considered somewhat outdated — a subject to be pondered by beleaguered academics, a handful of museum conservators, and a small, albeit growing number of hobbyist bookbinders.

That the history of British bookbinding remains obscure is a shame, not least because it overlooks the trade’s significant societal impact, particularly during its height during the 19th and early-20th century.

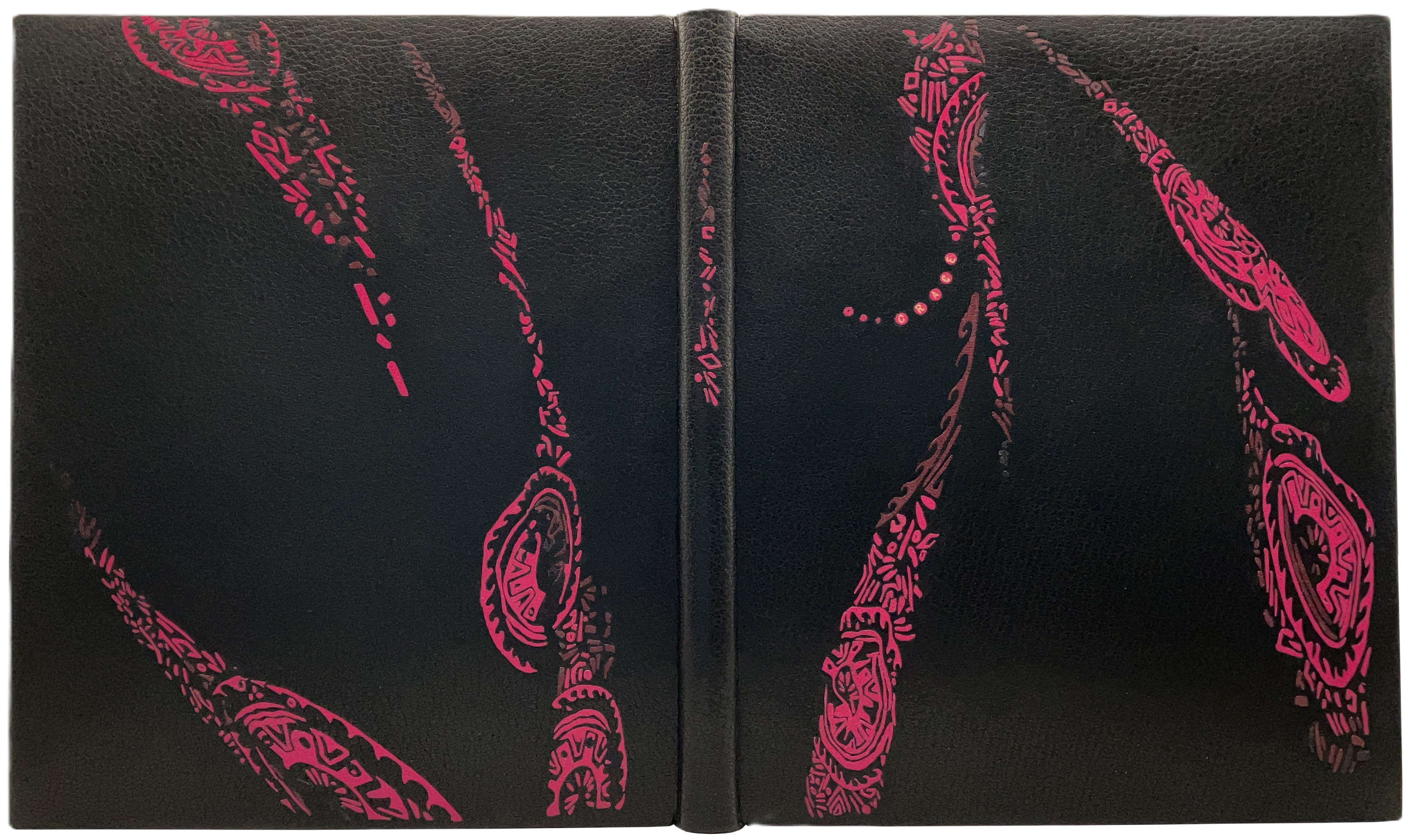

Grace, a collection of photographs of Nick Cave by Derek Ridgers and Danny Flynn, bound by Eri Funazaki in 2024.

In response to rapid industrialisation and growing literacy rates, it was English binderies in particular who developed their techniques to produce high quality books for a mass audience. They implemented decorative techniques designed for expensive leather on cheaper book cloth, adding hand-marbled endpaper to the text blocks, and moved away from aesthetically pleasing, yet laborious styles of stitching developed in France, to the quicker, and stronger styles of Kettle and Coptic style stitching, on sturdy linen bands, to hold pages together.

While English bookbinding technically advanced in this period, the trades’ commitment to quality — including hand lettering titles and patterns with pure gold leaf — meant that, for the first time, books were not just the vestige of the wealthy to be used as ornaments or denote status. Accessibility meant that books could be considered objects with utility and purpose, a technology with the power to change society.

Shifting belief in the possibility of well crafted and designed books is at the heart of ‘Bound Together: Modern British Bookbinding’, an exhibition hosted by Petersfield Museum and Art Gallery, and centres around the work of the bookbinder and artist Roger Powell. Having established a bindery in his home in Froxfield, near Petersfield, in 1947, Powell devoted five decades to fine bookbinding, and in doing so, made significant contributions to the field of early manuscript conservation and restoration, as well as the then emerging field of ‘designer’ bookbinding, in which classical bookbinding techniques are built upon with contemporary artistic trends and bespoke craftsmanship.

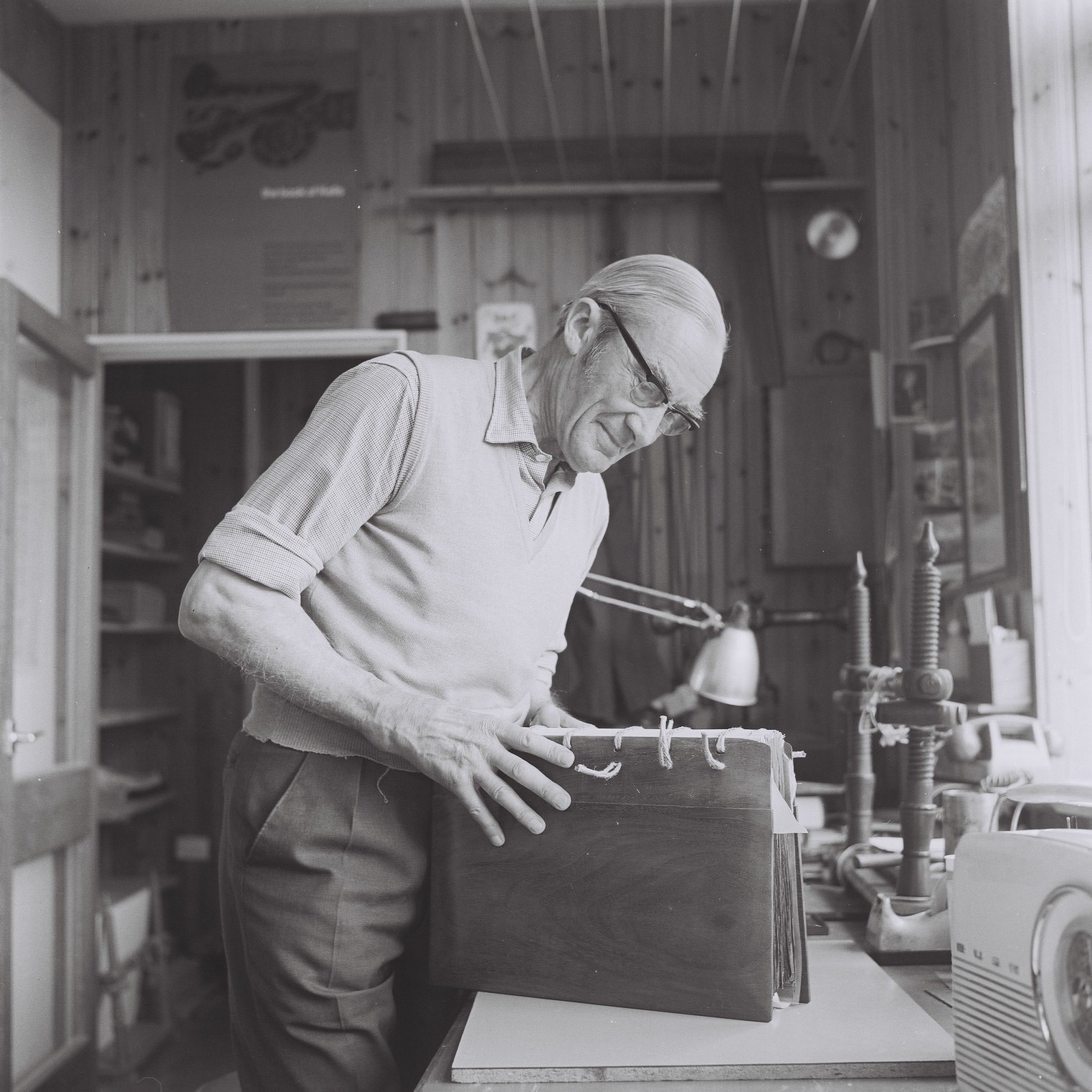

Roger Powell in his workshop at the Slade in the 1970s

Powell’s artistic endeavours were cultivated through the values of the Arts-and-Crafts Movement of the 19th century. With figures including Ford Madox Brown, Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, who Powell would eventually be contracted to produce work for, the movement was a reaction to the impacts of the industrial revolution on design and craft, and the belief that even the poorest in society deserved to own well-made ornaments that were decorated by hand and produced by individual craftspeople.

After serving in the First World War and following a brief, unsuccessful stint as a poultry farmer, Powell enrolled in the Central School of Arts & Crafts and trained as a bookbinder. It was here where he became interested in the relationship between a book’s structure and its design, and the question of how they could complement, rather than be independent of each other.

Hymns Ancient and Modern, bound by Roger Powell and Peter Waters at Froxfield sometime between 1955–60.

Such preoccupations are central to any modern bookbinder’s practice. Whether one is a professional or, like myself, an amateur, the creation of even the simplest notebook requires a consideration over its utility — who is the book intended for? Is it something to be used and carried around, or kept on a desk? Do the pages need to lay flat? Such questions are useful in deciding the kinds of materials best suited for the book, what kind of stitching is necessary to hold the book together and, central to many bookbinding projects, whether the codex will require a glued spine to keep it sturdy.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Powell once said: ‘I regard books as three dimensional, articulated objects, intended for use’ — an ethos evident in some of his early bindings of family Bibles, in which decorative features such as gold-leaf dots and embossed squares were arranged around the raised bands on a book’s spine. This symmetrical pattern not only had a practical use case — to show future restorers where the pages had been stitched — but also reflected the thought process of the bookbinder, asserting their role in the construction and development of the book itself.

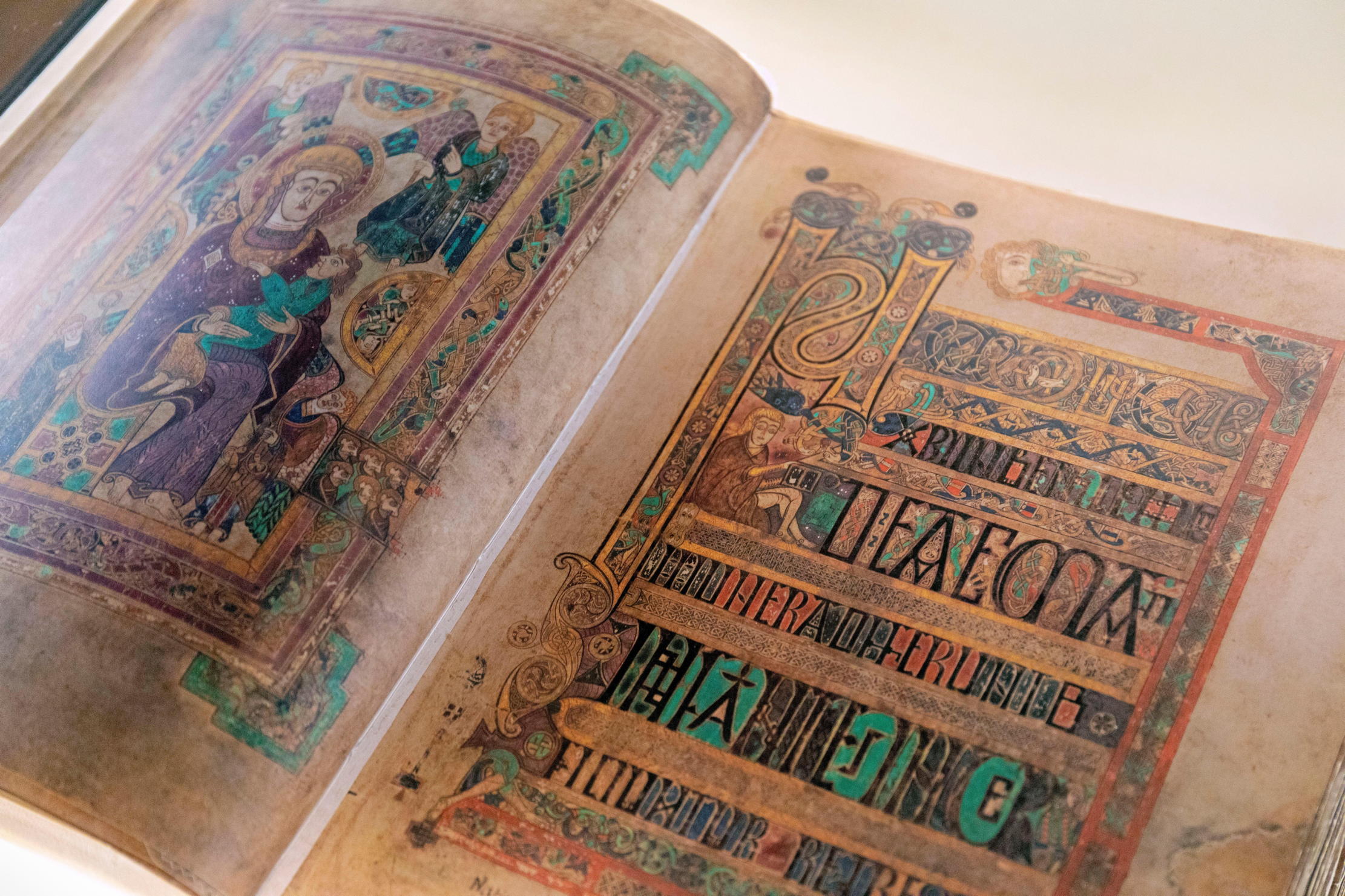

Perhaps, Powell’s legacy lies not just in his famous bindings, among them the historic rebind of the Book of Kells in 1953, but also in the reminder that the architecture of objects we hold everyday are made with human hands, that to derive pleasure from reading should not be considered a wholly individual experience.

The Book of Kells, rebound by Powell in 1953

This reminder is perhaps more relevant today than it was in Powell’s time. The dominance of Kindles and Ebooks, as well as the ever-shrinking profit margins for authors and publishers, has made the process of book publishing less economically valuable, particularly as AI programs, trained on swathes of pirated books, threaten to usurp what is left of the industry. Coupled with increasing library closures, and the shift to tablets over physical books in schools and universities, some people question if physical, printed books designed to be used will continue to exist in the future. Might we see a return to the physical book as a luxury ornament within the next decade or two?

There are some signs of hope. On social media platforms like TikTok, Instagram and Youtube, a younger, digitally native audience are taking up bookbinding, adapting classical techniques to create bespoke notebooks, and custom-bound versions of their favourite online fan fiction.

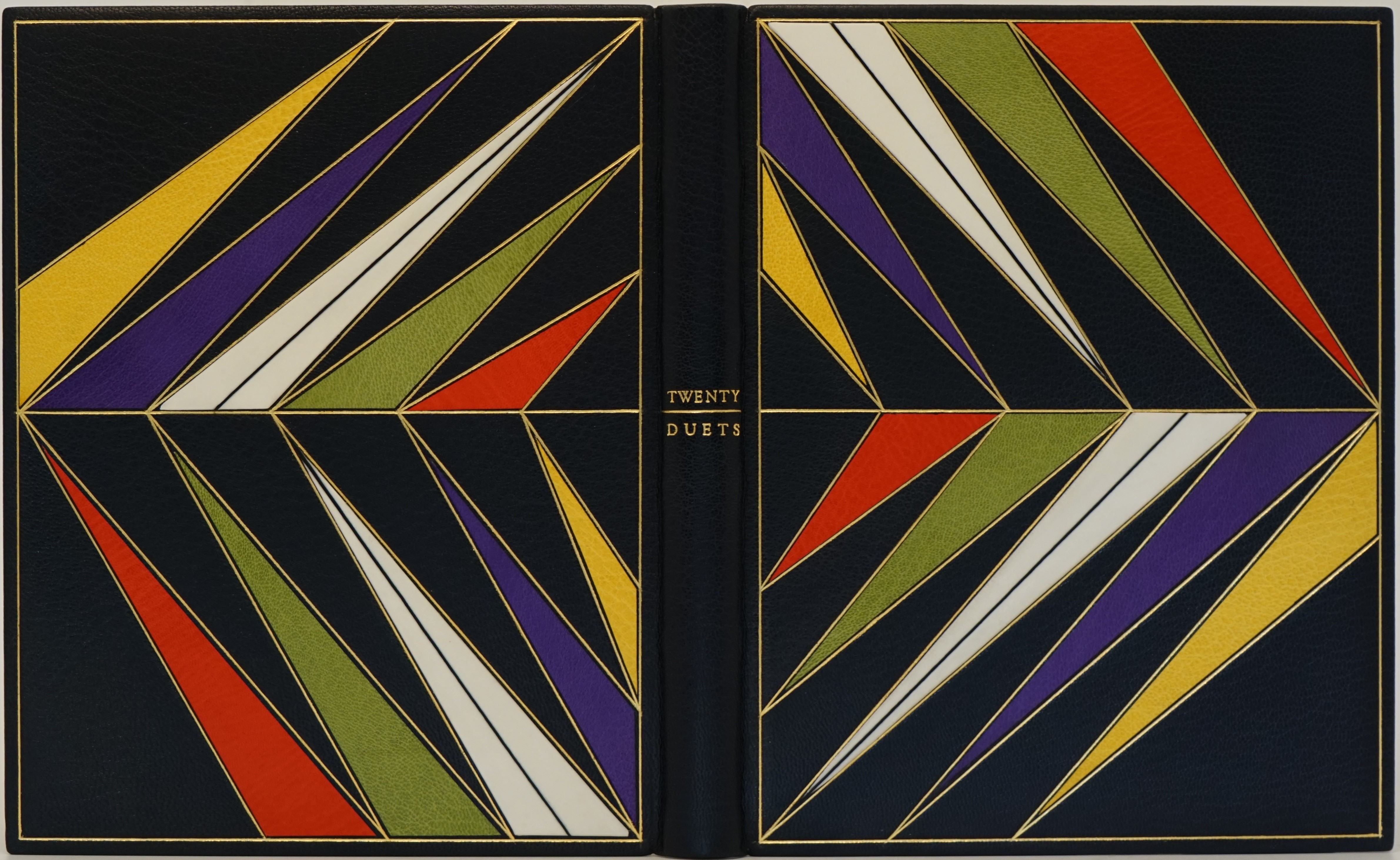

Twenty Duets by Peter Lawrence and Paul Dunmall. A 'collaboration essaying the challenging proposition of using Jazz improvisation as a model for wood-engraving', this edition was bound by Stuart Brockman.

Meanwhile, skilled bookbinders, many of whom are part of the UK’s Society of Bookbinders, have found sources of income through bespoke commissions of classic novels and re-binds of old family heirlooms. The revival of interest in handbound books isn’t just limited to individual hobbyists either, as some independent publishers, notably the London-based Tangerine Press, have distinguished themselves in a saturated market with a focus on physical copies, all bound in silk thread and Japanese paper, and put together by hand.

While it is unlikely that the trade of bookbinding will ever be as culturally impactful as it was during the time of Roger Powell, it is clear that his influence, even beyond books, remains strong. Even in the digital age, where delivery apps and subscription services tend to obfuscate those who produce and distribute the items we use daily and take for granted, his work should remind us that nothing is truly automated — that to exist in this world relies on the hands of others.

Bound Together: Modern British Bookbinding is at Petersfield Museum and Art Gallery until May 3

Hussein Kesvani is a writer and freelance media producer based in London. He has a background in journalism, and has published work in The Guardian, The Observer, The Fence and the New Yorker among others, and was longlisted for the Orwell Prize for Political Writing in 2020. In his limited free time, he is a self-taught bookbinder, with an interest in contemporary book arts and repair methods.

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life

-

Sanderson's new collection is inspired by The King's pride and joy — his Gloucestershire garden

Sanderson's new collection is inspired by The King's pride and joy — his Gloucestershire gardenDesigners from Sanderson have immersed themselves in The King's garden at Highgrove to create a new collection of fabric and wallpaper which celebrates his long-standing dedication to Nature and biodiversity.

By Arabella Youens

-

'That’s the real recipe for creating emotion': Birley Bakery's Vincent Zanardi's consuming passions

'That’s the real recipe for creating emotion': Birley Bakery's Vincent Zanardi's consuming passionsVincent Zanardi reveals the present from his grandfather that he'd never sell and his most memorable meal.

By Rosie Paterson

-

‘Large Welsh choirs have long been an obsession’: Accessories designer and ‘Sunday Times’ bestselling author Anya Hindmarch’s consuming passions

‘Large Welsh choirs have long been an obsession’: Accessories designer and ‘Sunday Times’ bestselling author Anya Hindmarch’s consuming passionsAnya Hindmarch reveals what gets her up in the morning, who her aesthetic hero is and the hotel she could go back and back to (sort of).

By Rosie Paterson

-

The Ravenna Palazzo where Byron lived and loved is now a museum dedicated to his memory — and it's just been toured by Queen Camilla

The Ravenna Palazzo where Byron lived and loved is now a museum dedicated to his memory — and it's just been toured by Queen CamillaOn a Royal State Visit that coincided with her wedding anniversary to His Majesty King, the Queen found a moment to tour a newly reopened museum devoted to the Romantic poet.

By Carla Passino

-

Good things come in threes: Sir Cecil Beaton's love of flowers, fashion and fabulous friends in a trio of exhibitions

Good things come in threes: Sir Cecil Beaton's love of flowers, fashion and fabulous friends in a trio of exhibitionsIt’s been 45 years since Sir Cecil Beaton died, but he has inspired not one, not two, but three new exhibitions this year.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Film star, resistance fighter and civil rights activist: The life and times of Josephine Baker, 50 years on from her death

Film star, resistance fighter and civil rights activist: The life and times of Josephine Baker, 50 years on from her deathJosephine Baker was an American-born actress and dancer, who would go on to take France by storm and become one of Europe’s highest-paid performers. She also happened to be a Second World War spy.

By Amy Serafin

-

Meet the willow weaving artist whose work is popular on both sides of the pond

Meet the willow weaving artist whose work is popular on both sides of the pondThis summer, Laura Ellen Bacon's work stars in two different exhibitions.

By Carla Passino

-

Chloe Dalton: The woman who swapped top-level geopolitics to rescue a baby hare

Chloe Dalton: The woman who swapped top-level geopolitics to rescue a baby hareAs an expert foreign policy adviser, Chloe Dalton's life revolved around international travel and walking the corridors of power. Then a chance encounter while out on a walk changed her life forever.

By Toby Keel

-

From California to Cornwall: How surfing became a cornerstone of Cornish culture

From California to Cornwall: How surfing became a cornerstone of Cornish cultureA new exhibition at National Maritime Museum Cornwall celebrates a century of surf culture and reveals how the county became a global leader in surf innovation and conservation.

By Emma Lavelle