The war hero and diplomat who mastered the art of making mazes

Randoll Coate bluffed his way into 'labyrinthology' with a chance comment at a dinner party, and ended up making a 30-year second carer of it.

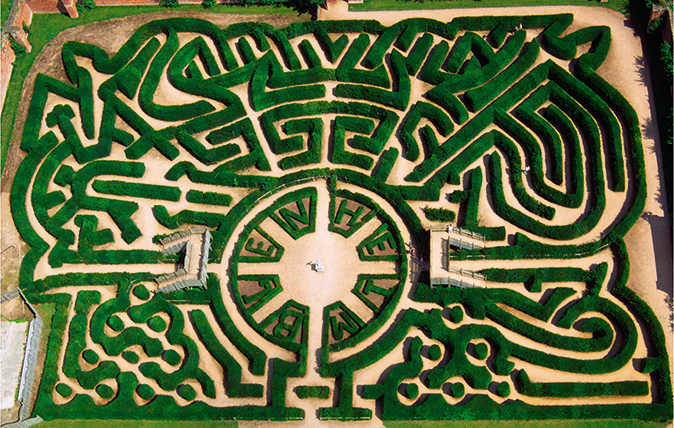

Last year, Blenheim Palace celebrated the 25th anniversary of the opening of the Marlborough Hedge Maze, a thing of ingenious symbolism and dense yew hedges, made of 3,000 trees, whose thickness means that it is better now than when it was planted in 1987.

A place of wonder, if also (enjoyable) frustration to visitors attempting to ‘solve’ it, the maze takes on a different aspect when one of the two viewing platforms is climbed. Then, it reveals the beauty of its design, inspired by the trophies of war on the skyline of the house.

‘My design incorporated flags flying, trumpets blaring, lances thrusting and pyramids of cannon balls for firing,’ wrote the designer Randoll Coate, who died in 2005 at the age of 96. Coate, who often worked, as at Blenheim, with Adrian Fisher, deserves to be called the father of the modern maze, even though he only turned to ‘labyrinthology’ (his word) after his retirement from a diplomatic career.

Maze-making requires a certain type of mind—inventive, witty, learned, deep. Those at least were some of Coate’s qualities. From an English family living in Switzerland who ran a shop in Geneva called Old England, he grew up in Lausanne. A godmother supported his time at Oriel College, Oxford, to which he won a scholarship. At the outbreak of the Second World War, he attempted to put his fluent French and German to use, only to find that he was offered a job living undercover in Romania. As Romanian was not one of his languages, he joined the Intelligence Corps.

In 1941, he volunteered for the Operation Archery Commando raid in Norway, noticing, as he dashed back to the landing craft after a hair-raising but successful mission, a little wooden Madonna and child from a Christmas crèche, dropped by a German soldier. It still decorates the top of the family Christmas tree.

Later, he was parachuted into Greece and only avoided being shot by partisans (he’d encountered a group that wasn’t expecting him) by showing them a cross he wore around his neck. It was inscribed with the Lord’s Prayer in tiny Greek letters, having been given to him by a Greek girlfriend in Oxford. He remained with the partisans, helping to liberate Kalamata on the southern Peloponnese.

On demobilisation, Coate joined the Foreign Office, with which he served in Salonika, Brussels, Leopoldville, Rome, The Hague, Buenos Aires and Stockholm, accompanied, from 1955, by his wife, Pamela. His final posting was as First Secretary in the embassy in Oslo.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

When he took early retirement in 1967, there was no thought of designing mazes. That passion, which would absorb the last 30 years of his life, was sparked by a chance comment made by the chatelaine of a house in Flanders, who remarked over dinner that ‘my place calls for a maze’.

‘Madame,’ he replied, ‘you are speaking to a maze-maker.’

Plans had reached an advanced stage when the authorities put an end to them by laying a road through the park. Another opportunity was presented by his brother-in-law, Allan Shiach. In 1975, he wanted a maze for the Mill at Lechlade, in Gloucestershire, which he and his wife, Kathy, had recently bought.

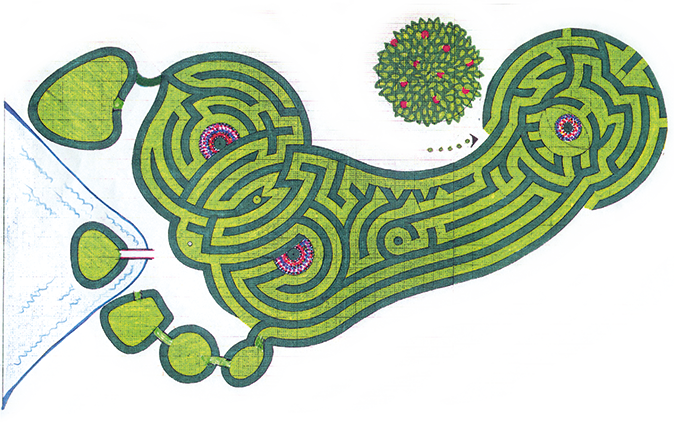

The idea originated while the Shiachs and the Coates were staying at Circeo, south of Rome, supposedly the place where Ulysses was seduced by Circe. This inspired a maze in the form of Circe’s footprint, for which Coate took a print of Kathy’s own foot made on clay. When enlarged to maze scale, this proved to be too large for the garden available and, as attempts to buy some fields from the neighbouring farmer came to nought, a solution (albeit an expensive one) was found by placing one toe on a specially created island in the river that runs by the house.

Called The Imprint of Man, the design can be read from the upstairs windows of the house: an organic, sweeping pattern of whorls and curved parallel lines. The last, Coate once wrote, had always delighted him, whether as ‘the glistening furrows of a neat ploughed field, the trim, serried ranks of vineyards, the parallel layers of rock upheavals, the trooping of the Colour, [or] the sartorial elegance of zebras’.

However, the maze is far more intricate than it looks. When different elements are isolated, they can be read as symbols—more than 100 of them. As Coate triumphantly recorded, they’re ordered numerically: the two sexes, the three persons of the Trinity, the four elements, the five senses and so on, up to the 26 letters of the alphabet and a Noah’s Ark with some 30 animals. These hidden symbols overlap one another, so they’re best appreciated with the aid of paper and coloured crayons. Fortunately, Coate left a deconstruction for the uninitiated (or lazy) to puzzle them out, as he did for every maze he designed.

Given this level of complexity, it’s no surprise to find that every maze that Coate designed is a one-off. Thereafter, several of Coate’s mazes were made overseas—in Belgium, Sweden, Italy, Argentina and elsewhere. Of British opportunities, a particularly suitable one arose in 1980, when the soon-to-be Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie, dreamt of a maze, which he described in his enthronement address. This inspired Lady Brunner of Greys Court, Oxfordshire, to commission a maze rich in Christian symbolism from Coate and his collaborator Adrian Fisher (who was featured in the BBC documentary excerpted below). In it can be found the Crown of Thorns, the Seven Days of Creation and the Twelve Apostles.

Made of turf and only 85ft across, the linear character of The Archbishop’s Maze recalls the labyrinths that can be found in medieval cathedrals such as Chartres. For the International Garden Festival at Liverpool in 1984, Coate and Fisher, helped by the writer and gardener Graham Burgess, designed a Beatles Maze (pictured above), at the centre of which was a Yellow Submarine. The paths, formed of bricks crossing water, take the shape of the world’s listening ears. It won two gold medals.

Another festival maze was made at Bath the same year. The centre or goal of the maze is a domed mosaic representing Bath’s ancient past. If ever there was a country-house owner in need of a maze, that man is the Marquess of Bath. He commissioned not only one, but two mazes, the first to fill a dull parterre beneath his bedroom window and the second to be a pendant to that. The iconography he left entirely to Coate and he chose the Sun and the Moon.

Don’t think, however, that the meanings stop there. The mazes also re-tell the myth of the Minotaur, which includes the original labyrinth. Accordingly, hidden in the Sun maze are depictions of Bacchus laughing, the Minotaur, Theseus’s ship, his helmet, his sword and the double-edged axe known as a labrys, an attribute of Cretan female deities.

Although the Longleat Maze shows one side of Coate’s creativity, the pommerie maze at Combermere Abbey in Shropshire is equally original. Looking for the best site, Coate hit upon the walled garden, only to be told it had been earmarked for an orchard.

‘Splendid,’ he cried. ‘We’ll have a maze entirely made of espaliered fruit trees.’ The fact you could see through them did nothing to dampen his enthusiasm.

‘Ideal—and innovative!’ he exclaimed. ‘The compounded transparency of the espaliers will have a most baffling maze effect.’

To some, the design will invite a contemplation on the cultural and spiritual meaning of apples. Others may just think that it looks exceedingly pretty in the spring.

Clive Aslet

-

'That’s the real recipe for creating emotion': Birley Bakery's Vincent Zanardi's consuming passions

'That’s the real recipe for creating emotion': Birley Bakery's Vincent Zanardi's consuming passionsVincent Zanardi reveals the present from his grandfather that he'd never sell and his most memorable meal.

By Rosie Paterson

-

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin

The Business Class product that spawned a generation of knock-offs: What it’s like to fly in Qatar Airways’ Qsuite cabinQatar Airways’ Qsuite cabin has been setting the standard for Business Class travel since it was introduced in 2017.

By Rosie Paterson