The rise of reading dogs

Therapy dogs are helping children all over Britain with literacy problems

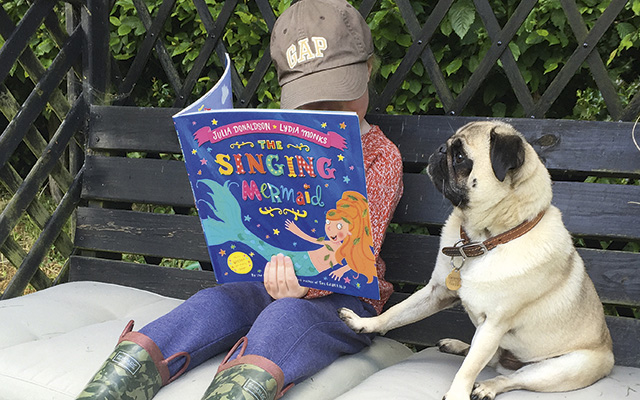

Picture the scene. In a primary school in south-east England, a small boy is reading aloud. He sits on his own, his only audience the dog on his knee. A neatly groomed pug, with characteristic dark mask and black-tipped ears, the dog is falling asleep, burrowing deeper into the boy’s lap.

Unexpectedly, the boy begins to cry. The dog’s handler is at his side immediately. ‘Doug the Pug’s bored,’ offers the boy by way of explanation. ‘He’s gone to sleep.’ The handler denies it. ‘But his eyes are closed.’ She tells him that Doug has closed his eyes to envisage the wonderful story the boy is reading. Upset, the boy is implacable: ‘He’s snoring.’ ‘He’s purring with pleasure, just as pugs do.’ Uncertain at first, the boy is reassured; he reads to the end of the story.

The pug in question is five-year-old Doug, a therapy dog that, for the past three years, has accompanied his owner, Cate Archer, to schools in London and Buckinghamshire as part of a nationwide initiative to tackle literacy problems among British children. The bulk of Doug’s work is as a ‘reading dog’: he provides a friendly audience for children to read to.

Some of Doug’s children have learning difficulties or attention disorders; some lack confidence. Others are kinaesthetic learners: instead of fiddling in their seats, they stroke Doug’s ears and hug the bid- dable little dog. For these children, acquiring basic literacy skills isn’t only challenging, but stressful. The presence of a dog alters the classroom atmosphere. ‘Doug encourages children to think school is a lovely place to be,’ says Mrs Archer. ‘He goes on school trips and, in one case, has a stall at the school’s summer fair.’ The impact on pupils’ progress academic, social and behavioural can be marked.

On the surface, it’s an eccentric-sounding idea, but a growing body of research indi- cates the correlation of stress and inhibited learning. In the USA, the Human-Animal Bond Research Initiative Foundation recently announced the funding of a research project at Yale University to examine the effect of dogs on children’s stress.

Here in Britain, Doug’s work with school- children is coordinated by the charity Pets As Therapy, as part of its Read 2 Dogs project. So successful have this and similar projects proved that Pets As Therapy currently has some 200 schools on its waiting list for therapy dogs like Doug. The charitable arm of the Kennel Club provides an umbrella for this and related initiatives, called the Bark & Read Foundation. Other participating organisations include Caring Canines, Dogs Helping Kids, Building Understanding of Dogs and Reading Education Assistance Dogs.

Mrs Archer explains that Pets As Therapy discourages dog handlers from involving themselves too closely with a child’s education. Instead, the dogs’ role is to help children regain a love of learning in a safe, unthreatening environment. To this end, Bark & Read charities consider dogs of all breeds as potential

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

reading dogs: canines on their lists range from pugs and whippets to golden retrievers and labradors. What matters is the predictability and trustworthiness of a dog, so that handlers, teachers and staff can be confident of its reaction to different sounds and behaviour. Google is a golden retriever belonging to Sandy Childs,

Head of Outreach for the Secondary Behaviour Support Service of the London borough of Enfield. He’s the second dog that Mrs Childs has worked with in schools. So notable was the effect Google had on some of the children he encountered that Mrs Childs decided to build a learning programme around him, encouraging children not only to read, but also to develop their creative writing skills and emotional and social intelligence.

Google has even been mentioned in an Ofsted Report. About Enfield’s Chace Community School, inspectors wrote in 2013: ‘Google the dog through the Bark & Read scheme has been especially successful in motivating boys to read and write.’

At the age of seven, Abbie Cavill from Brightlingsea was diagnosed with brain cavernomas. The operation necessary for treat- ment of the condition was frightening for the little girl and she became withdrawn and sub- sequently angry. Happily, Abbie’s headmistress Claire Claydon was a Pets As Therapy volunteer with her own therapy dog, Spike. Part of Abbie’s rehabilitation included time spent with him and he became Abbie’s reading dog.

As Mrs Archer has discovered, an advantage reading dogs have over hard-worked teachers is their ability to persuade children that they’re always interested. ‘Doug tilts his face and cocks his head. He looks as if he really loves his work. A relationship forms between Doug and the children; he becomes a great motivator, sitting beside the child, encouraging him or her.’

Given the success to date of dogs like Doug, Google and Spike, Bark & Read looks set to provide many more children with such motivation and encouragement. ‘Doug the Pug’ (5m Publishing, £7.95) is published on February 2, 2016

How to get involved

All dogs taking part in Bark & Read schemes are carefully assessed for suitability by vets. Dogs must be gentle and calm, without threatening behavioural

patterns, and not barkers. In most cases, dogs must have attained a minimum age before they can be considered as therapy dogs. Participating charities have local and national coordinators.

Alternatively, readers who would like to take part in Bark & Read can telephone the Kennel Club’s Ciara Farrell on 020–7518 1009 or email ciara.farrell@thekennelclub.org.uk

For further information, visit www.thekennelclub.org.uk/our-resources/bark-and-read/how-togetinvolved

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country Life

Six rural properties with space, charm and endless views, as seen in Country LifeWe take a look at some of the best houses to come to the market via Country Life in the past week.

By Toby Keel

-

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwards

Exploring the countryside is essential for our wellbeing, but Right to Roam is going backwardsCampaigners in England often point to Scotland as an example of how brilliantly Right to Roam works, but it's not all it's cracked up to be, says Patrick Galbraith.

By Patrick Galbraith