How to light a fire perfectly, every single time

From the ‘teepee’ to the ‘log cabin’ method, knowing how to light a fire and keep the home fires burning has long been a skill worth knowing, says Matthew Dennison.

‘Give me… a good book, or a good newspaper, and sit me down afore a good fire and I ask no better,’ says Joe Gargery in Dickens’s Great Expectations. This sentiment is still widely shared today.

Once, open fires were a simple fact of life, their purpose strictly practical, and, for many country dwellers, an open fire is first and foremost a means of heating.

Jerome Mayhew, managing director of adventure-activity company Go Ape, is renowned for his ability to kindle fires – apparently from nothing – on the pebbly beaches of the string of uninhabited islets that fringe the southernmost tip of Co Cork, within sight of his holiday house.

At home in Suffolk – where cold wind blows all too easily down his Tudor chimneys – he concentrates his skill on indoor fires. ‘Living in a house that we can’t afford to heat properly makes a fire rather more practical than romantic,’ he says.

‘As soon as the fire is lit, rooms transform. Although the room may not suddenly become hot, at least the flow of air is reversed in the chimney.’

Get your kindling and fuel ready

The first step is make sure you have a flow of air and dry materials. Don’t be afraid to get creative. ‘After scavenging sodden wood from the nearby bog, we had to heat it in the electric oven to dry it sufficiently to light the fire,’ says Jerome Mayhew of a family trip to the Cairngorms.

‘I can still remember the intense odour of wet sap as we shivered in the kitchen.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Four foolproof ways to build a fire

Once you've got your materials ready, you need to put them together. Here are the four most useful ways of building a fire:

The teepee

Make a wigwam of upward-pointing sticks which encircle a core of dry tinder.

The sandwich

Put together horizontal layers of crumpled newspaper, topped by kindling and, initially, small logs, resembling a layered cake or trifle.

The log cabin

Form a Jenga-style criss-cross structure of sticks forms a neat, squat tower, filled with tinder, with further kindling and small logs on top.

The upside-down

The idea in this case is to place the largest logs on the bottom, with tinder and kindling on top. It’s particularly popular for lighting larger log-burning stoves.

How to get perfect tinder, all year round

Material for tinder is readily available all year round for vigilant country dwellers. Pinecones in particular have a long ‘harvesting’ season as different conifer species drop their cones across a period of several months. Dry pinecones have the advantage of catching fire quickly, as well as their pleasing, albeit mild, scent. They are also markedly more attractive in hearth-side baskets or boxes than discarded newspapers.

Lovers of citrus fruits do well to dry orange peel, ideally in ribbons like old-fashioned curling papers, as a supplement to more conventional tinder.

Gettint the airflow right

Fires, however, like ancient boilers, can be temperamental: a lit fire will not necessarily remain alight without a degree of vigilance. A good pair of bellows is invaluable, blasting a supply of oxygen to feed the flames and rekindle smouldering sticks and logs.

If you don’t have bellows? Tobias Jones, author of A Place of Refuge, suggests using lengths of old copper pipe in place of conventional bellows – a trick he used to keep up his nine open fires burning while living in the woods in Suffolk.

‘The key was to blow hard,’ Mr Jones says, adding ruefully that the exception came when he forgot to ‘take my mouth off the end of the pipe, sucked in air and ended up, very stupidly, with lungs painfully full of smoke’.

Drawing the fire

In some instances, ensuring a good draw from the outset can mitigate the need for bellows. Smaller fireplaces can be ‘shielded’ with an open sheet of broadsheet newspaper to encourage a good draw. Nineteenth-century tole trays are also useful for this purpose and often more generously sized.

Sit back and enjoy

Sally Coulthard, author of The Little Book of Building Fires, suggests that the current popularity of open fires is part of the same ‘back-to-basics, feel-good’ philosophy that has seen a resurgence in the taste for camping, baking bread and growing vegetables.

‘Open fires have made a glittering comeback in the past few years; there are lots of reasons why, both economic and environmental,’ she says, ‘but perhaps it’s also true that central heating is, well, just a little bit soulless. Not everything worth having can come at the push of a button.’

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025Mondays's quiz tests your knowledge on English kings, astronomy and fashion.

By James Fisher

-

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'

Welcome to the modern party barn, where disco balls are 'non-negotiable'A party barn is the ultimate good-time utopia, devoid of the toil of a home gym or the practicalities of a home office. Modern efforts are a world away from the draughty, hay-bales-and-a-hi-fi set-up of yesteryear.

By Annabel Dixon

-

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025Mondays's quiz tests your knowledge on English kings, astronomy and fashion.

By James Fisher

-

School dinner puddings, Scrabble tiles and Antonio Banderas: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 11, 2025

School dinner puddings, Scrabble tiles and Antonio Banderas: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 11, 2025Friday's quiz asks you to name one of Britain's most beautiful places, and ponders the distance of a marathon.

By Toby Keel

-

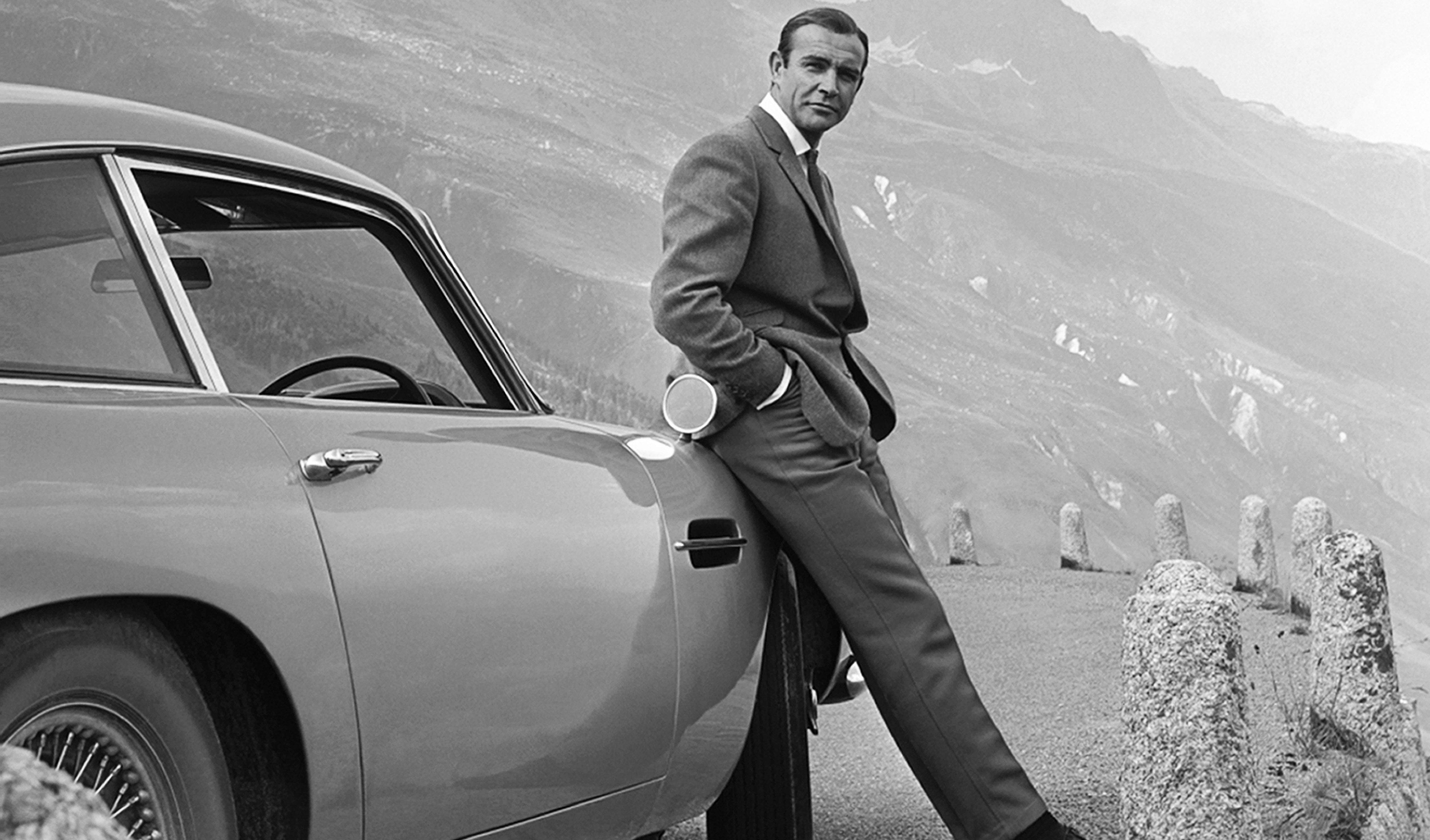

Bond's Aston Martin and Welsh rarebit: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 10, 2025

Bond's Aston Martin and Welsh rarebit: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 10, 2025Thursday's quiz celebrates pedestrian crossings and tests your language skills.

By Toby Keel

-

Scary sharks, the T-Rex and fabulous city views: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 9, 2025

Scary sharks, the T-Rex and fabulous city views: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 9, 2025Wednesday's quiz takes in restaurants, beautiful cities and more.

By Toby Keel

-

The beautiful island bridge, an otter's life and Churchill's TXT speech: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 8, 2025

The beautiful island bridge, an otter's life and Churchill's TXT speech: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 8, 2025Tuesday's quiz takes in cricket pitches, frittatas and more.

By Toby Keel

-

An architectural masterpiece, frog eyelids and Wordsworth's house: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 7, 2025

An architectural masterpiece, frog eyelids and Wordsworth's house: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 7, 2025Plus the longest bridge in Europe, all in Monday's quiz.

By Toby Keel

-

Hold the front page: How to find the ladybird hiding on this week's Country Life cover

Hold the front page: How to find the ladybird hiding on this week's Country Life coverDid you struggle to find the ladybird on this week's Country Life front cover? You weren't the only one.

By Rosie Paterson

-

The poisonous tree lighting up your garden, and name that Farrow & Ball colour: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 4, 2025

The poisonous tree lighting up your garden, and name that Farrow & Ball colour: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 4, 2025Plus classic children's literature and one of Europe's most beautiful cities in Friday's quiz.

By Toby Keel