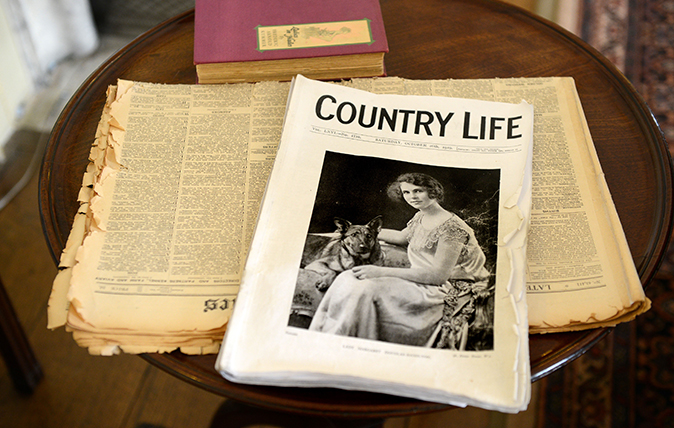

Edward Hudson: The tale of the man who founded Country Life, 125 years ago this month

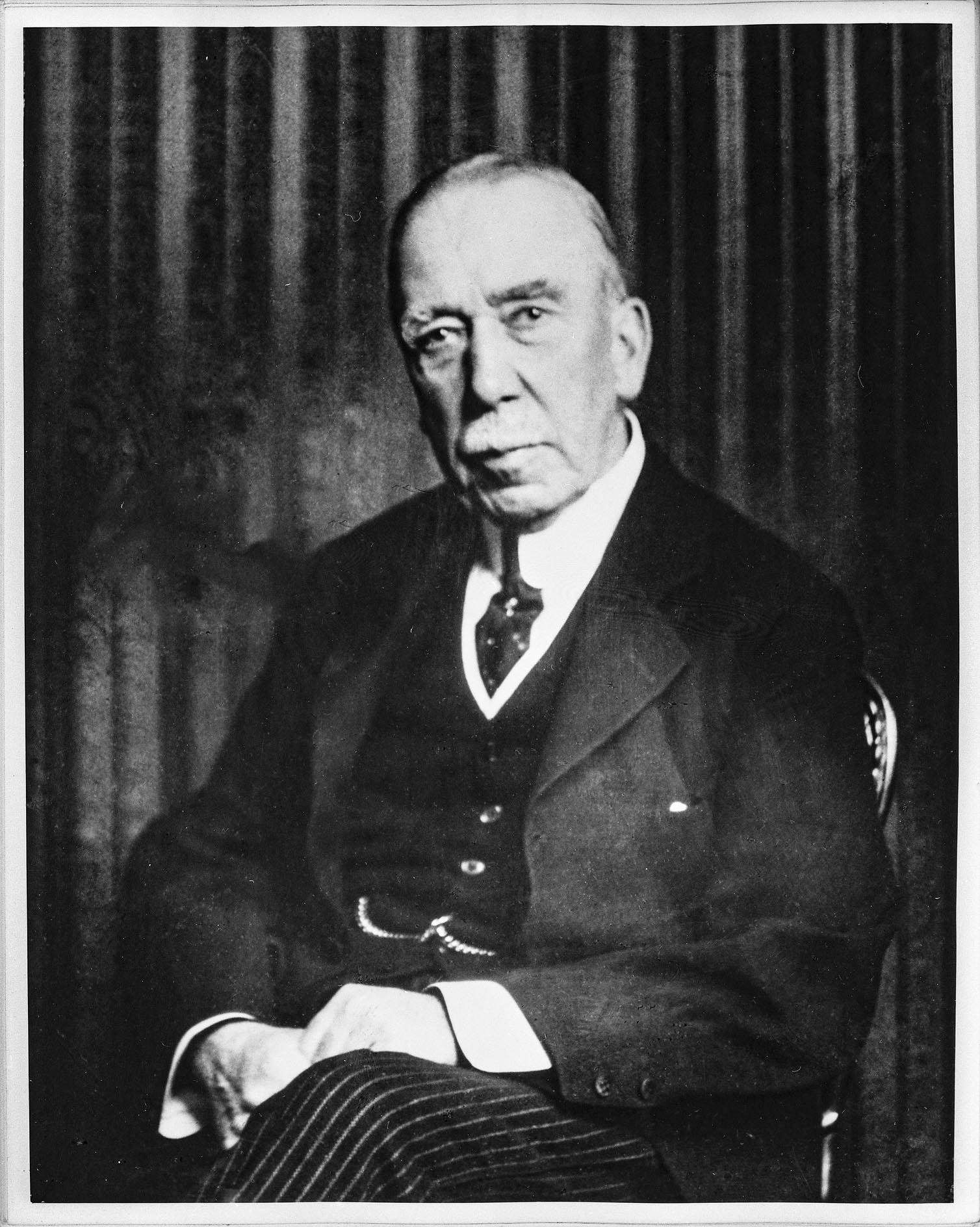

A publisher, innovator and shrewd businessman with strong connections to the Liberal political establishment, Edward Hudson was the visionary founder of Country Life 125 years ago. Clive Aslet revisits his remarkable life.

Edward Hudson would enter the Country Life offices like a whirlwind. Staff who had temporarily put their feet on the table — on press days, they might not go home before midnight — took them down again. Bells rang; pages that were typeset by the compositors in the attics of the building and printed by presses in the basement were rushed into his presence: each one was personally approved by the proprietor. ‘His energy was tremendous, and was almost in the nature of bustle,’ remembered Bernard Darwin, employed in 1908 to write on the important early Country Life subject of golf, ‘…he could be brusque if anything or anybody was not up to time.’ Even worse would have befallen the individual who suggested that production standards could be allowed to slip: the hurry did not prevent Hudson from taking infinite pains to exact the best result from his team. ‘After this hectic time, Mr Hudson would dash off elsewhere, and the office would once more settle down with a gentle sigh.’

Country Life, founded in 1897, was the love of Hudson’s life, only rivalled — before his late marriage — by the grand amour he developed for the glamorous Portuguese cellist Guilhermina Suggia, to whom he was briefly engaged. (He bought her the Montagnana cello she is shown playing in the portrait by Augustus John, initially commissioned by Hudson and now owned by Tate.) It became the centre of a publishing empire, with Country Life Books reusing plates from the magazine and a diffusion range, feminine and domestic, in Homes and Gardens.

Hudson’s own interests were those of his main publication. Sometimes, they spread beyond it into the world of politics. Through his friend and business associate George (later Lord) Riddell, managing director of the News of the World and an ally of Lloyd George, he had the ear of the Liberal establishment, freely bending on behalf of important causes.

The power of the press was reinforced by the behind-the-scenes influence exerted by the man himself; the architectural tenor of the War Graves Commission, established at the end of the First World War to provide cemeteries for the Fallen, exactly mirrored the Country Life point of view. Yet the means by which Hudson projected his vision remain mysterious, for the man was considerably less than charismatic. In spongebag trousers and watchchain, he had a naturally lugubrious cast of face, with bloodhound eyes and a moustache covering his long upper lip. Acutely diffident, he suffered agonies when making a speech of any kind, even at the magazine’s Christmas dinner.

His response to ancient country houses, set amid noble parks, was essentially aesthetic — an approach that would have baffled most aristocratic owners other than the Souls. ‘All his life he searched for beauty for himself and his beloved Country Life,’ wrote ‘A Friend’ in the obituary columns of The Times after his death (possibly Lutyens); ‘and this quest he pursued like a hunter, alert, groping, discarding, and finding.’ Obsessive perfectionism made some treasured projects, such as The Dictionary of English Furniture, published in the 1920s, uneconomic; but the reputation they established was beyond price.

Born in 1854, Hudson was the son of a printer. He was in his forties when new techniques of printing half-tone blocks were developed by George Meisenbach of Munich. They provided the means by which high-quality photographs could be reproduced within a page of text and Hudson saw that the potential could be exploited by a magazine. Hudson and Kearns, the family firm, first tried a title called Racing Illustrated, devoted to the personalities, human and equine, of the turf. It lasted only a year, before being folded into a new publication of broader appeal: Country Life Illustrated, the title emphasising the novelty and quality of the photographs.

At first, the aroma of stable and kennel remained strong, but, after a year or two, it was replaced by roses and pot pourri as articles on country houses and gardens grew longer. The change of emphasis came, it was said, after Hudson had taken a consumptive brother on tours of the Home Counties, for the sake of the fresh air. They passed long drives and formed a romantic image of the battlemented or porticoed splendours at the far end, replete with family collections and packs of hounds.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

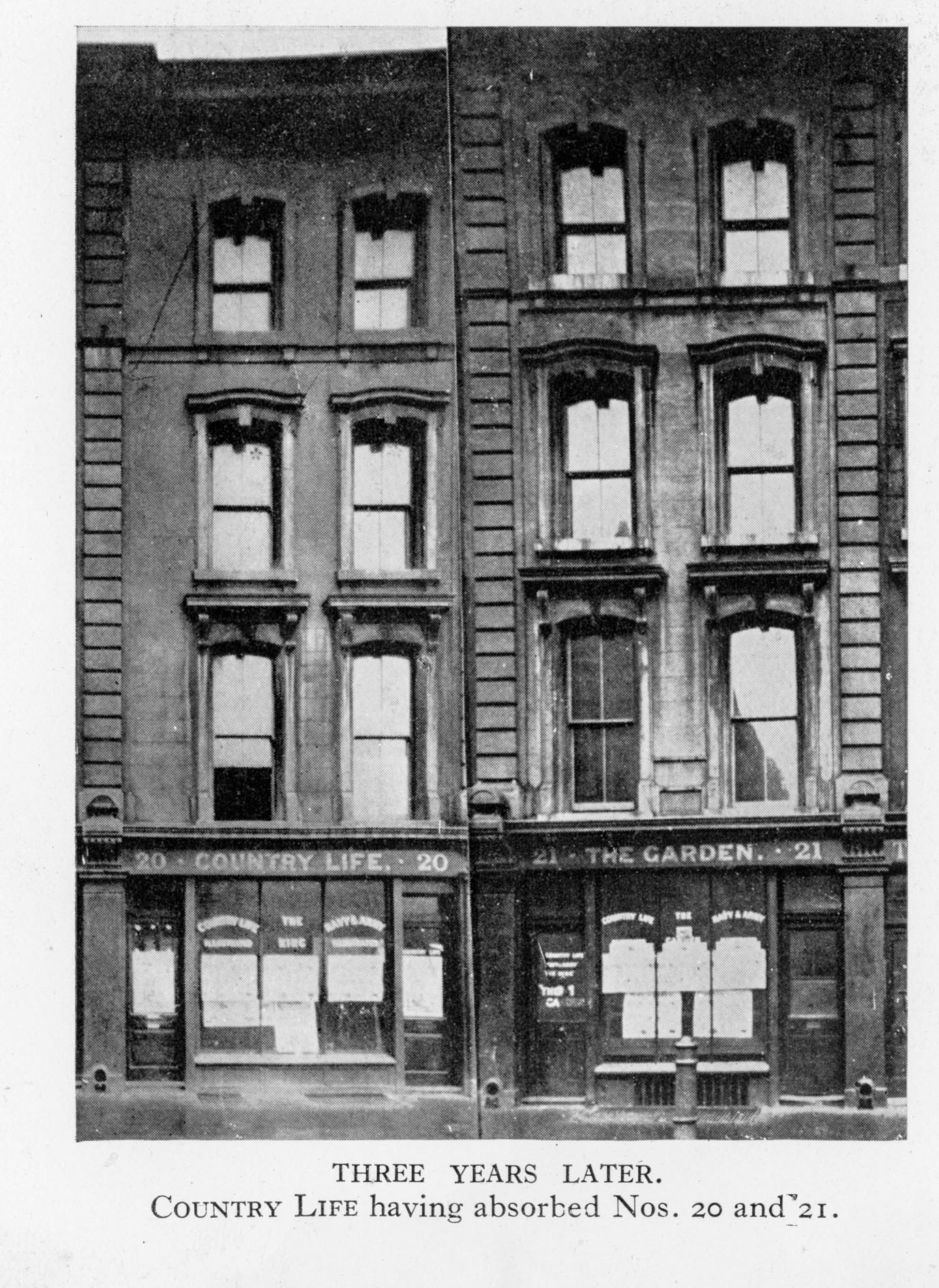

Soon, Hudson had settled on Country Life’s winning and unique editorial formula. Crucially, it proved a magnet for estate and country-house advertisements, for Hudson was both an idealist and a pragmatist. The loftiness of his ambition was recognised in 1913, when Lord Runciman called Country Life ‘the keeper of the architectural conscience of the nation’ (page 68). That did not, however, prevent him from going into partnership with the Liberal MP and magazine publisher George Newnes, famous for gossipy titles such as Tit-Bits and The Strand Magazine.

Although Newnes, like Riddell, became a peer, no such honour devolved on Hudson; perhaps he was regarded as too inarticulate for the House of Lords. Nevertheless, he had an outstanding talent — not for self-presentation, as he never wrote himself, but in picking the right people. His first triumph was to recruit Gertrude Jekyll, the socially well-connected craftswoman-turned-garden designer to edit the gardening pages. The year 1908 saw Darwin take command of the magazine’s golfing coverage. (Hudson had become one of the three owners of the Walton Heath Golf Club.) In 1907, Henry Avray Tipping — previously a contributor to The Garden, which had been absorbed by Country Life two years before — had been appointed Architectural Editor, bringing a new level of scholarship to the country-house articles.

Tipping’s tiny diary for 1908 (all that survives from his papers, which he ordered to be destroyed at his death) show him touring the country in Hudson’s Rolls-Royce, sometimes with Hudson himself: the chauffeur Perkins had to avoid getting bogged down in the mud that was one of the perils of country roads. That year, Tipping produced 51 articles for Country Life itself, as well as the third volume of Gardens Old and New for Country Life Books.

It was Jekyll who introduced Hudson to Lutyens in about 1899. The architect regarded Hudson variously as a ‘brick’ and an ‘angel’; to Hudson, Lutyens was quite simply a genius and he took every opportunity of promoting his cause. This began, practically on first meeting, with the commission to build Deanery Garden, hidden behind an ancient wall that already stood on the site, in the Berkshire town of Sonning; it was featured in Country Life as ‘the house of a man with a hobby — viz., rose-growing and wall-gardening’. Within a few years, Lutyens would be designing the Country Life office, an early masterpiece in his English ‘Wrenaissance’ style, which was followed by the remodelling of Lindisfarne Castle in Northumberland for Hudson.

Lindisfarne became the ultimate expression of the romanticism that motivated both men. Lutyens delighted in its remoteness and twice-daily isolation when the tide came up — he brought up the raven he believed every castle required, on a train — but the Prince and Princess of Wales (George V and Queen Mary) could not wait to get back to the comforts of Bamburgh Castle: for a sailor, observed Lutyens, the Prince expressed surprising concern about the tide. The visit left Hudson in a terrible state of nerves. In the 1920s, Lutyens created his third country house, Plumpton Place in Sussex: the beautiful manor house was kept as a stage set in the middle of its lake and Hudson occupied a cottage — the view and the garden were all.

For a while, the friends had London houses next to each other in Queen Anne’s Gate. There, Hudson would lovingly caress and gaze at an exquisite piece of china or furniture he had brought home, to the point, wrote ‘A Friend’ in The Times, it became ‘almost a living inmate’ of the house. Both men had an austere attitude to soft furnishing, Hudson sitting bolt upright on a hard chair when reading a book. Lytton Strachey bemoaned the rigours of Lindisfarne when he visited. But Hudson’s eye for antiques, which he enjoyed for their patina and authenticity, was not only discriminating, but ahead of its time.

Strangely, the proprietor of Country Life was never wholly at ease in the country. At Lindisfarne, he was distressed to find the gamekeeper trapping the rabbits in a field he rented. ‘These rabbits I take it belong to me,’ he wrote to the agent, ‘anyway the rent I pay for the field would include rabbits. I propose to cultivate these rabbits, and I should be glad if you will kindly instruct the gamekeeper that he is not to interfere with them.’ He had to be told the rabbits were destroying the crops and, as this was 1918, the War Agricultural Committee would disapprove.

But to Hudson, Lindisfarne was a place of the imagination — a work of art, where the Country Life photographer Charles Latham would capture Lutyens’s daughters in the style of a painting by Vermeer. ‘I wish that I could thank him again for all the beauty he gathered round him and enabled others to share,’ wrote ‘A Friend’. Those who have been lucky enough to work on the magazine that he founded feel the same.

-

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of spring

‘David Hockney 25’ at the Fondation Louis Vuitton: Britain’s most influential contemporary artist pops up in Paris to remind us all of the joys of springThe biggest-ever David Hockney show has opened inside the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris — in time for the season that the artist has become synonymous with.

By Amy Serafin Published

-

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humour

High Wardington House: A warm, characterful home that shows just what can be achieved with thought, invention and humourAt High Wardington House in Oxfordshire — the home of Mr and Mrs Norman Hudson — a pre-eminent country house adviser has created a home from a 300-year-old farmhouse and farmyard. Jeremy Musson explains; photography by Will Pryce for Country Life.

By Jeremy Musson Published

-

22 things you probably never knew about Country Life

22 things you probably never knew about Country LifeI never knew that about Country Life…

By Agnes Stamp Published

-

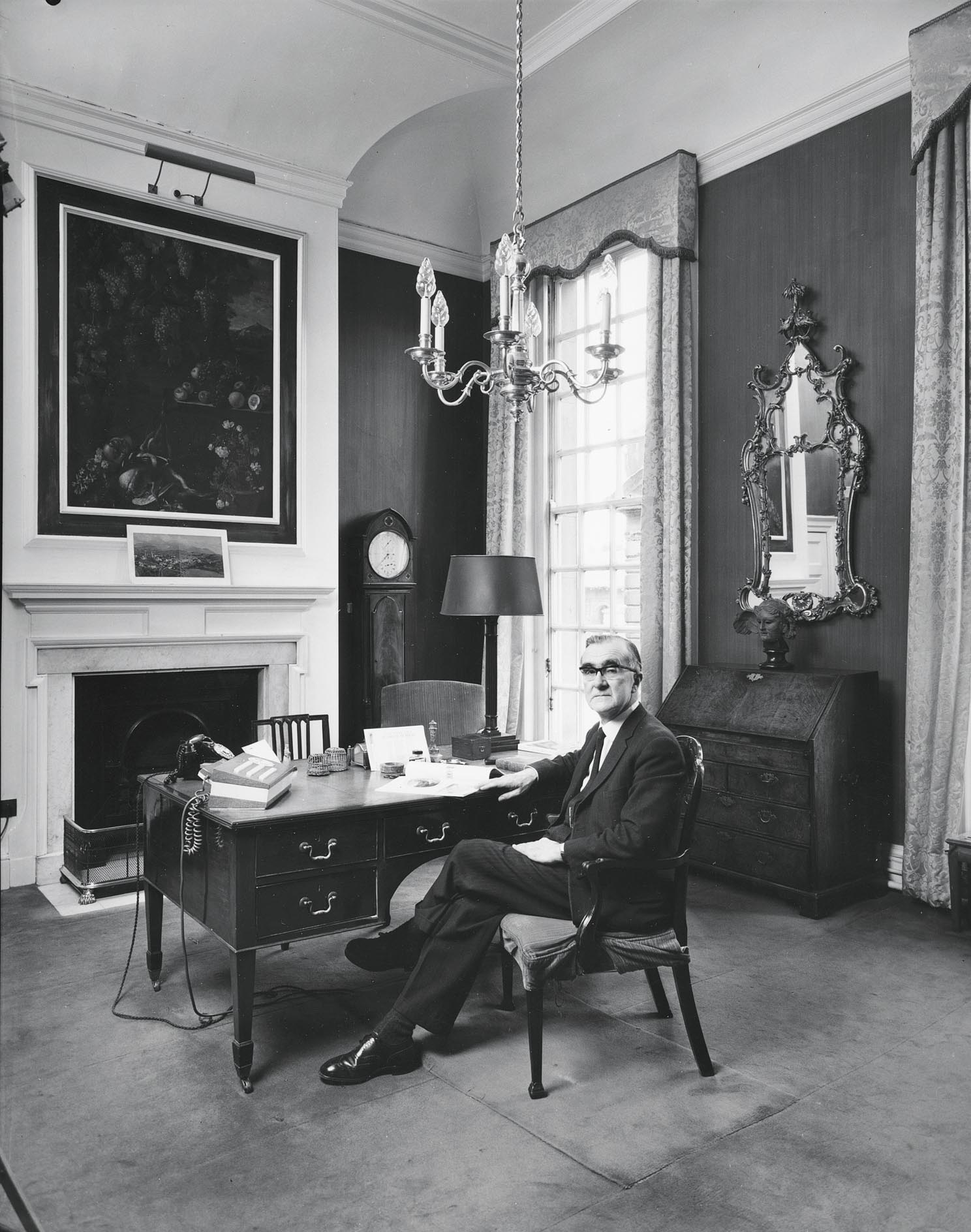

How Country Life’s 125-year journey began, thanks to a visionary founder

How Country Life’s 125-year journey began, thanks to a visionary founderAs Country Life celebrates its 125th anniversary, Michael Hall tells the remarkable story of how the magazine came into being under the exacting eye of its founding editor, Edward Hudson.

By Michael Hall Published

-

Digitising Country Life's 125 years of history

Digitising Country Life's 125 years of historyA hugely ambitious initiative to digitise the contents of the Country Life photographic archive during the magazine's 125th anniversary year promises to make its riches properly accessible to everyone for the first time. John Goodall explains more.

By John Goodall Published