How Country Life’s 125-year journey began, thanks to a visionary founder

As Country Life celebrates its 125th anniversary, Michael Hall tells the remarkable story of how the magazine came into being under the exacting eye of its founding editor, Edward Hudson.

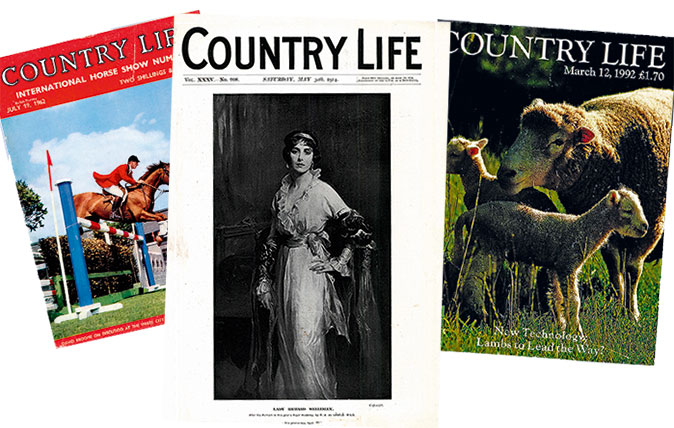

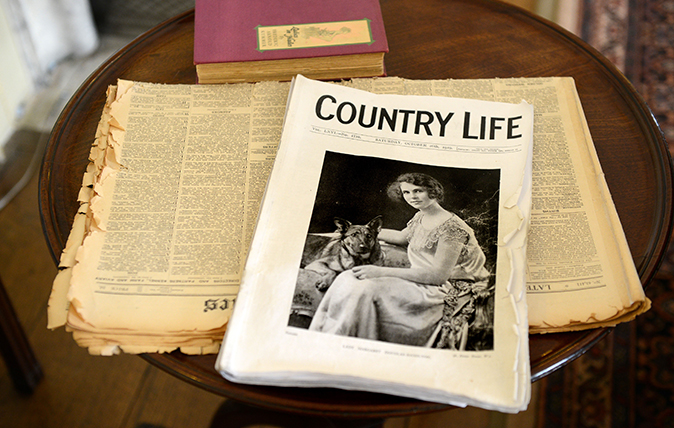

On January 8, 1897, commuters browsing station bookstalls while waiting for their trains were confronted by an intriguing new magazine: Country Life Illustrated. Subtitled ‘A journal for all interested in country life and country pursuits, with which is incorporated Racing Illustrated’, it was a luxurious folio printed on heavy, glossy paper and — as its name promised — was well illustrated with large black-and-white photographs, so richly inked that they feel slightly grainy to the touch.

Leafing through it now compared to a modern copy is to see the caterpillar beside the butterfly. Like most periodicals of the time, its front cover is occupied by advertisements — which were not finally confined inside until 1941 — but they are not yet for houses: ‘The New Raw Hide Riding Whip by Swaine & Adeney’ sits alongside Cadbury’s cocoa and Osmond bicycles. The Frontispiece is no ‘girl in pearls’, but the stoutly middle-aged Earl of Suffolk, beaming benignly.

Sport is prominent, with articles on the Devon and Somerset Staghounds and (less expectedly) the rules of Association Football. There is an article on a country house, but with only two illustrations and a page of vapid text about cooing doves and ‘mailed knights’, the account of Baddesley Clinton probably interested readers less than an article on the Princess of Wales’s pet dogs.

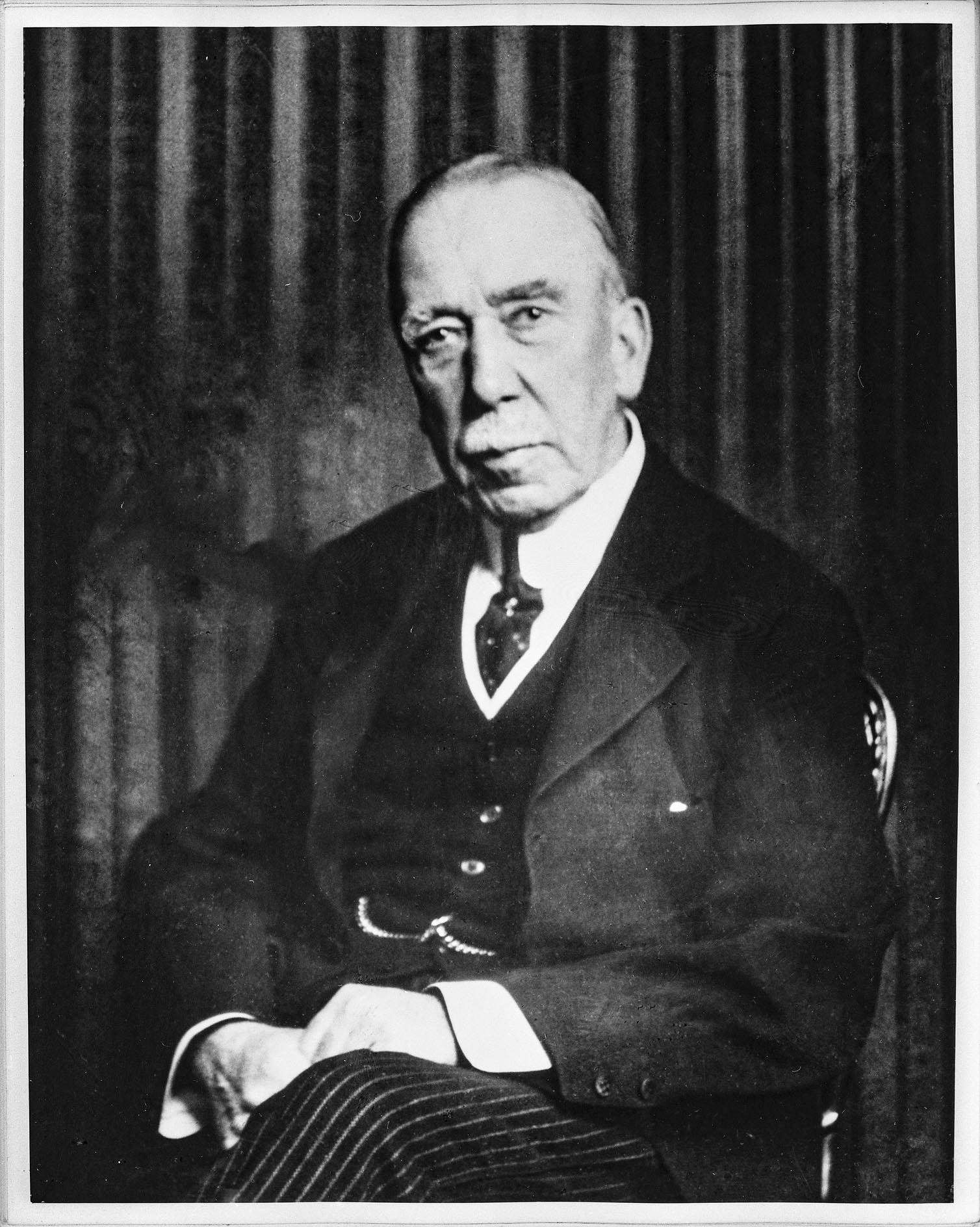

It was an odd mixture, but it worked and was rapidly refined by the remarkable man who conceived Country Life and was to steer its fortunes with passionate single-mindedness for the next 40 years. This was Edward Hudson (1854–1936), born into a prosperous middle-class family with a big house near Hyde Park. Having attended neither public school nor university, he was articled to a solicitor when he was 15, but was soon bored and persuaded his father to let him enter the family business, Hudson & Kearns, a firm of printers based in Southwark.

In about 1890, after he had succeeded his father, he oversaw a transformation of the company under the impact of new technology, invented in Germany in the early 1880s, that made the printing of mass-market periodicals illustrated with photographs a commercial reality for the first time.

That is why the turn of the century was such a golden period for the foundation of illustrated magazines, including not only Country Life, but also The Studio, The Architectural Review and The Burlington Magazine. Much of the appeal of his new magazine was due to Hudson’s exacting eye for the quality of its printing.

Once it was clear that Country Life was a success, he imported the latest presses from America and was unrelenting in his scrutiny of the results. ‘I am told,’ wrote Bernard Darwin, in a 50th-anniversary history of the magazine, ‘that in the earliest days of the paper he inspected every sheet from the machines in order to pass it before allowing the machines to run.’

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

As Hudson & Kearns were only printers, Country Life was created in partnership with a leading publisher of periodicals, George Newnes. The magazine’s editorial offices were in two modest houses in Tavistock Street, in Covent Garden, but advertising was dealt with in Newnes’s office, round the corner in Southampton Street — this quarter of London was, until the 1970s, the Fleet Street of the magazine-publishing world (as the presence there today of The Lady still testifies).

Newnes’s fortunes were based on the spectacular success of his magazine Tit-Bits, founded in 1881, but a combination of unwise investments and alcoholism led him to cede control of his company to George Riddell, later Lord Riddell, owner of the News of the World, already notorious for its sensational journalism.

Years later, Riddell reflected that, if his association with the News of the World hampered his entry into Heaven, ‘I will urge in extenuation my connection with Country Life’.

There’s little doubt that the idea of Country Life crystallised in Hudson’s mind when, in 1896, he and Riddell were discussing what to do with one of their joint ventures, Racing Illustrated, which had disappointing sales (and was to be incorporated into the new magazine).

This conversation is often said to have taken place at Riddell’s golf club, Walton Heath in Surrey, but as the club wasn’t founded until 1904, that can’t be true and if there had been a connection between the conception of Country Life and a golf course, Darwin would surely have mentioned it in his well-informed anniversary history, as he was the magazine’s golfing correspondent.

That doesn’t obscure the fact that Country Life was the product of the imagination and commercial instincts of two dynamic businessmen. Our knowledge of Hudson’s personality is shaped by the many descriptions of his tongue-tied, clumsy social manner, which seem to be borne out by the glum, walrus look of the only good portrait photograph of him, taken in old age.

However, this was not how he appeared to the staff at Country Life. ‘As soon as Mr Hudson was in his room,’ wrote Darwin, ‘signs and portents were not long wanting; a livelier air seemed to blow down the passage. If anyone, having for a moment nothing to do, had composed himself with his feet on the table, he instantly took them down again. Bells began to ring and summonses to be issued.’

It would be interesting to know how quickly Hudson and Riddell grasped the significance of the property advertising that was to be so important to the magazine’s future prosperity. The appearance of Country Life coincided with the emergence of the modern profession of the estate agent, either by the evolution of long-established firms of land agents, such as Savills, or by the creation of new partnerships, notably Knight Frank, founded (as Knight, Frank & Rutley) in 1896.

Such firms benefited from the break-up of large agricultural estates, a process encouraged by the long recession in arable farming that began in the 1870s and the impact of death duties, introduced in 1894.

However, much of the property advertising in Country Life focused on London and the Home Counties, where land and houses had, for centuries, been traded very actively, so the magazine simply provided a new, well-distributed and well-illustrated vehicle for a strong and established market. That is certainly how it seemed to Lord Lee of Fareham, who, in 1909, saw his future home, Chequers in Buckinghamshire, advertised in Country Life.

Later, he recalled his first sight of the magazine: ‘In January 1897, when serving in Canada, I was turning over the newly arrived English papers in the Montreal Club and was thrilled to come across a new weekly journal of which the outstanding feature, as it seemed to me, was an intoxicating array of temptation in the shape of English country houses — Tudor, Jacobean, Georgian and what not — which were at the disposal of any homesick exile who could make a fortune overseas and retire to his native land.’

Those words bring us to the final element that enabled Country Life not just to be launched successfully, but also to thrive to the present day: Hudson’s vision of what it represented. He was never the magazine’s editor, nor was he a contributor, but he was, in many ways, its ideal reader. He was a Londoner by birth and upbringing and it was almost by chance that he developed a love of the countryside and what would now be called its heritage.

Prompted by the need to entertain an invalid brother, he toured in his motor car around the cathedrals, churches, country houses and gardens of England and fell in love with what he saw. Country Life was the product of a romantic idealisation of the countryside that was reflected in many other aspects of contemporary culture, from the Arts-and-Crafts movement to the foundation in 1895 of the National Trust.

Guided by that ideal, Hudson proved to be a talent-spotter of genius. In the decade after the foundation of the magazine, he gathered the team that would shape its future. First, there were the architectural and garden photographers, beginning with Charles Latham, who fused documentary accuracy with nostalgic glamour. Then, there were the writers, most significantly Gertrude Jekyll, who not only contributed a column on gardening to the magazine, but also introduced Hudson to Edwin Lutyens.

Through Country Life, Hudson ardently promoted Lutyens’s work as an ideal demonstration of how the future of British culture could be guided by tradition. For Hudson, Lutyens designed that most beguiling of all Arts-and-Crafts houses, Deanery Garden in Sonning, Berkshire, and then, in 1904–5, new offices for Country Life, the architect’s first major Classical building, and the magazine’s home for the next 70 years.

Its completion marked the moment that Country Life came to maturity, coinciding, for example, with the arrival of Henry Avray Tipping as architectural editor and the transformation of the country-house articles into well-researched scholarship.

Country houses lie at the heart of the magazine’s ideal, not simply as subjects for historians, or material for advertising, but as an expression of a quintessentially British culture: rural, historical, conservative and creative. Country Life’s genius resides in its celebration of the place that rural life has in the national consciousness.

It appeals to an audience that has remained remarkably consistent in character and outlook, well summed up by Sir Roy Strong in his centenary history: ‘The magazine still stands for the civilised person in the old sense of the word, someone as much at home working in the garden as seeing an art exhibition, as fascinated by the nesting habits of birds as the restoration of a state bed, as concerned about pollution as much as who will win the Boat Race.’

It is a tribute to Edward Hudson’s visionary combination of editorial and commercial flair that all these elements were present in embryo in the magazine that those commuters first picked up 125 years ago this week.

Michael Hall is a former deputy editor and architectural editor of Country Life.

-

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa Harrison

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa HarrisonThe novelist, children's author and nature writer Melissa Harrison joins the podcast to talk about her love of the natural world and her new app, Encounter.

By James Fisher

-

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera season

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera seasonBy Annunciata Elwes

-

Edward Hudson: The tale of the man who founded Country Life, 125 years ago this month

Edward Hudson: The tale of the man who founded Country Life, 125 years ago this monthA publisher, innovator and shrewd businessman with strong connections to the Liberal political establishment, Edward Hudson was the visionary founder of Country Life 125 years ago. Clive Aslet revisits his remarkable life.

By Clive Aslet

-

22 things you probably never knew about Country Life

22 things you probably never knew about Country LifeI never knew that about Country Life…

By Agnes Stamp

-

Digitising Country Life's 125 years of history

Digitising Country Life's 125 years of historyA hugely ambitious initiative to digitise the contents of the Country Life photographic archive during the magazine's 125th anniversary year promises to make its riches properly accessible to everyone for the first time. John Goodall explains more.

By John Goodall