The compass: How a flawed, unreliable invention changed the world

Never mind satnav, it was the compass that revolutionised the way we travel.

‘Naughty elephants,’ my grandfather would say, in a tone of utter despair, as he struggled to teach me the different points of the compass, ‘squirt water. Do you get it now? N is for “naughty” and “north” and is here at the top. E is for “elephants” and “east” and is here on the right.’ There were certain core skills that he believed every child should master and reading a compass was one of them. Possibly, if he’d waited until I was five or six and was able to spell, he might have found the going a bit easier. Nevertheless, long before I went to prep school, I was a dab hand at navigation.

There are, of course, lots of different navigation methods. Mariners used to follow currents, winds and even fish. Viking sailors released birds in the belief that, if they didn’t return to the ship, there must be land nearby. Plants and trees have long guided travellers, as have the sun and the stars. My late mother found her way around London by way of shops and hotels – which led to some strangely circuitous routes, such as Oxford Circus to Bond Street Underground station via Liberty, Fenwick, Asprey, the Ritz, H. R. Owen, the Connaught and Claridge’s.

For the past 1,000 years or so, however, mankind has relied almost completely on the magnetic compass.

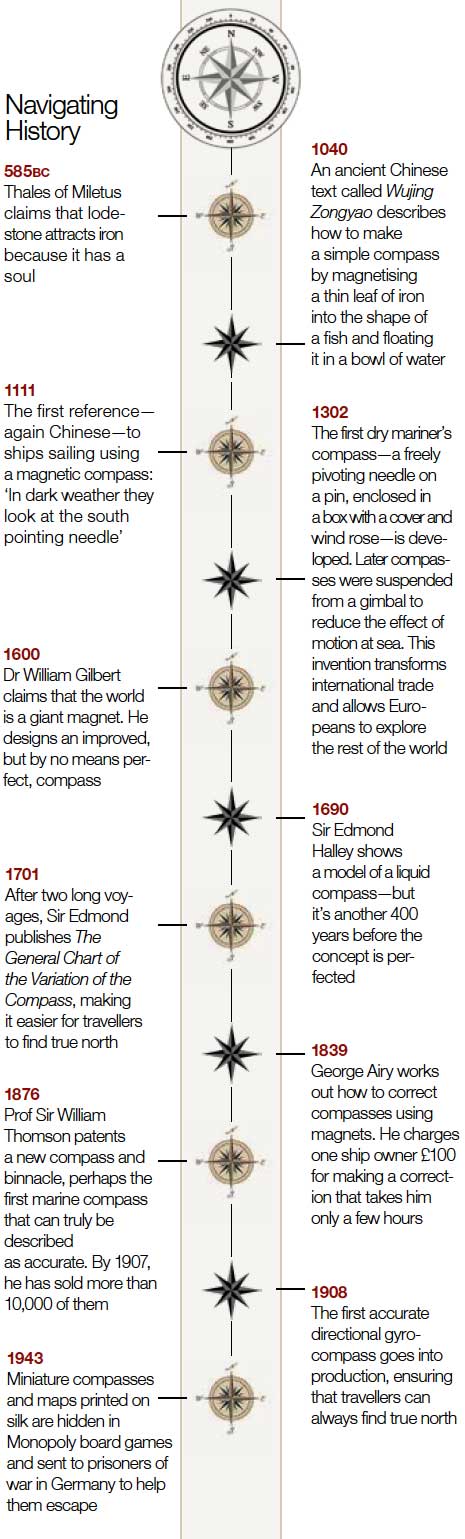

The first written reference to lodestone – a dull, grey rock that has the power to attract and magnetise iron and, if a sliver is suspended by a thread, will align itself north and south – is to be found in the 6th-century BC writings of the Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus.

However, it seems likely that the Chinese were the first to understand its potential. There are numerous mentions of it in Chinese literature from the 4th century BC onwards, when lodestone was employed for the purposes of divination. In the first century AD, for example, the Emperor Wang Mang possessed a primitive lodestone compass to ensure he could sit facing south, the imperial direction.

It’s unclear at what point the Chinese used such compasses for navigation, but the first definitive description of a directional compass – ‘a magnetic needle floating in a bowl of water’ – is in a book dated 1044.

Proof of the compass’s use in the West doesn’t appear until 1187, when an English Augustinian monk called Alexander Neckam wrote that when sailors ‘are ignorant to what point of the compass their ship’s course is directed, they touch the magnet with a needle. This then whirls around in a circle until, when its motion ceases, its point looks directly to the north’.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

During the latter half of the 13th century, some design modifications – including the addition of a ‘wind rose’, which made it possible to measure other directions in units or degrees, a gimbal to allow for the motion of the ship and a wooden box to protect the whole device – made the use of magnetic compasses practicable at sea.

In the space of a very short time, the merchant ships of Venice, Genoa, Pisa and Amalfi doubled the number of voyages they were able to make every year to the eastern Mediterranean, as navigation was now possible during the winter months.

"I say 'trusty compasses', but, for nine centuries, they were anything but"

Indeed, it would not be overstating it to say that the invention of the maritime compass had a very marked effect on international trade, as well as making it feasible for the European nations to start exploring and colonising distant parts of the world. Christopher Columbus, Hernán Cortés, Vasco da Gama, our own Sir Francis Drake and others of that ilk would never have got anywhere – or come back – without their trusty compasses.

Actually, I say 'trusty compasses', but, for nine centuries, they were anything but. The simple technology had several flaws. To begin with, even at their best, compasses point to magnetic north rather than geographic north. That they work at all is due to the molten iron in the Earth’s core, which has the effect of turning the whole planet into a giant magnet.

Like all magnets, Earth has two poles, one that attracts and one that repels. These poles aren’t aligned perfectly with true north or south and, to make it more confusing, they shift from place to place and over time, according to the movements of the magma. Magnetic variation at London in 1580, for example, was 11.15 east, but, by 1850, it had changed to 22.24 west. In 1950, it was measured at 9.07 west and it is still decreasing at the moment.

By the middle of the 15th century, navigators had identified the wandering pole, although it took several centuries to understand its cause. Various methods were tested to correct the deviation – or, to use the technical word, declination – of which charts and tables, created on the basis of previous observation, were the most accurate. Nevertheless, on long journeys, even a small deviation could send one hundreds of miles out of one’s way.

Another issue was the quality of the compass itself. After the Scilly naval disaster in 1707, when four British ships containing 2,000 men were lost as a result of a mistake in the fleet’s dead reckoning – which the Spanish call, somewhat mordantly, navegación de fantasía – an inspection of the fleet’s compasses was made. Of 506 instruments examined, only 73 could be said to be in anything close to working order.

Then there was the matter of interference. The introduction of greater quantities of iron in shipbuilding, beginning with iron nails and ending up with iron hulls, played havoc with the reliability of marine compasses.

Over the centuries, there has been a great deal of competition between different experts and manufacturers, with endless and generally unwarranted claims as to the reliability of one new compass over another. This isn’t so surprising when one considers that there were huge social and financial rewards for those who solved, or at least appeared to have solved, the various problems. In reality, it wasn’t until the end of the 19th century, when a more or less dependable version – the gyrocompass – was perfected, that travellers could rely on a single, completely trustworthy instrument.

I still have the piece that my grandfather utilised to teach me the rudiments of navigation, his First World War officer’s marching compass, for which he can have had very little use at the time, as he spent most of the war in charge of Woolwich Arsenal (the actual arsenal, not the football team). It has accompanied me on journeys through the Amazonian rainforest, across the Sahara, up the Zambezi and, somewhat more prosaically, along Offa’s Dyke, the Pennine Way and other National Trails.

I can’t say, in all honesty, that it’s entirely accurate. More than once, I’ve cursed it – especially the time I nearly found myself crossing accidentally into the Sudan – but I put up with its foibles as one puts up with the idiosyncrasies of an old friend. As Lord Bolingbroke said: ‘Truth lies within a little and certain compass, but error is immense.’

Jonathan Self

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.