Britain's beautiful green lanes: The charming remnants of leafier times, untouched by the modern world

Although they’re difficult to define, the charm of a green lane – be it a footpath, bridleway, byway or road – is its mystery and otherworldliness, says John Wright.

A natural tunnel of trees in the West Sussex countryside near Halnaker

Hogg Cliff Farm in west Dorset was my home for four years. I was newly married, highly impoverished and lacking transport, so a shopping expedition to our village involved a two-mile trek. Down the chalk-hill track, up again through the steep woodland path, across two fields and down, down the flinty and steeply banked Drift. Returning home involved two hill climbs, so shopping was done with considerable care.

The Drift is an ancient drove-road that allowed stock to be brought to and from our long-lost village market – and it’s a green lane.

Green lanes defy precise definition and have no legal status. They can be a footpath, bridleway, byway or road; they can be public or private. They can run for scores of miles or just for a hundred yards.

The general conception of them, however, is a rural trackway of some antiquity, which is unmetalled, often with high or overarching hedges and, on the less frequented lanes, sporting a sward – hence ‘green lane’.

Nearly every town possesses one somewhere, a memory of leafier times, although it may be in suburbia, next door to Coronation Street or on an industrial estate. There are, nevertheless, thousands of miles of green lanes largely untouched by the modern world and they are among the most enchanting and accessible delights of the countryside.

Knowledge of their origin is, however, often lost to us. Some will be Iron Age paths between fortifications, some a development of the deep, V-shaped boundary ditches between manors. The shorter ones may owe their existence to the necessity of accessing the ‘waste’ (the wild part of a manor left for the workers) for firewood and forageable plants. And then, of course, there are the drove-roads.

I know every inch of the Drift, from the riot of pink redcurrant flowers at the bottom, along elder, hawthorn, blackthorn and spindle, to the occasional stinkhorn fungus near the top. Halfway up is a gateway into a steeply sloping field and a green valley. Here, I always rest on the conveniently positioned and massively swollen stem of a once-laid hedging beech. On one late-night walk, we found fireflies illuminating the hawthorns like Christmas-tree lights.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Drift is high and free and airy. Unsurprisingly, Hell Lane is not. I discovered this well-known ‘holloway’ while on an excursion to photograph hedgerow plants around Bridport in west Dorset. The passage of people, animals, carts and floodwater over centuries has eroded the path to such a depth that the soft sandstone has formed near cliffs on either side.

It’s dark, damp and has an otherworldly feel, like a ruined cathedral. The walls are festooned with mosses, lichens, shade-loving plants and extensive and venerable graffiti. It is, above all, romantic.

Much poetry has resulted from our romantic view of green lanes – ‘Whene’er I walk with thought o’ercast, Along the old green lane’ – but this masks a darker history. Boundaries, wills and rights of way bring out the very worst in people and disagreements about access continue to this day. An example from 1840 finds Governor Darlaston defending his failure to remove a fallen tree obstructing a green lane under his care by insisting to the jury that ‘God Almighty put it there, and God Almighty shall remove it, for I will not’.

Green lanes appear to be favourite places for robbery and even murder. Ireland set the criminal standard low in 1844, with a murder by two brothers of an older man. The dispute that caused the unfortunate to be bludgeoned to death took place in the green lane under question.

Today, apart from the tiresome issue of landowners blocking public rights of way with barbed wire, notices promising damnation and shouts of abuse, there is the equally tiresome matter of who can use a green lane – the ‘who’ that people complain about being ‘off-roaders’. The latter, it is claimed, damage the lanes with their four-wheelers and motorbikes and frighten both horse and human.

Campaigning groups from either side have set up organisations defending their views. Legislation in 2006 largely settled the matter (although to no one’s complete satisfaction), limiting the use of green lanes by motorised vehicles to a few classes of lane. The legislation is complex to the point of incomprehensibility and so the arguments continue.

As a Nature lover and the proud owner of a four-wheel-drive, testosterone-powered pickup, I have mixed feelings. Perhaps the answer is to restrict off-road access to only me. I will be careful, I promise.

Country crossings: a stile guide

Steven Desmond climbs back through history to uncover the origins of the stile and understand why these charming country crossings

Credit: Getty

The art of the sunrise and sunset: How the greats have captured Nature's finest display

A truly spectacular sunrise or sunset is one of Nature’s greatest achievements. Jay Griffiths explores our timeless desire to capture

Dreamy properties in Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty

Green and pleasant.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old Masters

From Vinted to Velázquez: The younger generations' appetite for antiques and Old MastersThe younger generations’ appetite for everything vintage bodes well for the future, says Huon Mallalieu, at a time when an extraordinary Old Masters collection is about to go under the hammer.

By Huon Mallalieu

-

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comeback

In all its glory: One of Britain’s most striking moth species could be making a comebackThe Kentish glory moth has been absent from England and Wales for around 50 years.

By Jack Watkins

-

The battle of the bridge, Balloon Dogs and flat fish: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 15, 2025

The battle of the bridge, Balloon Dogs and flat fish: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 15, 2025Tuesday's quiz tests your knowledge on bridges, science, space, house prices and geography.

By James Fisher

-

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025

Jungle temples, pet snakes and the most expensive car in the world: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 14, 2025Mondays's quiz tests your knowledge on English kings, astronomy and fashion.

By James Fisher

-

School dinner puddings, Scrabble tiles and Antonio Banderas: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 11, 2025

School dinner puddings, Scrabble tiles and Antonio Banderas: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 11, 2025Friday's quiz asks you to name one of Britain's most beautiful places, and ponders the distance of a marathon.

By Toby Keel

-

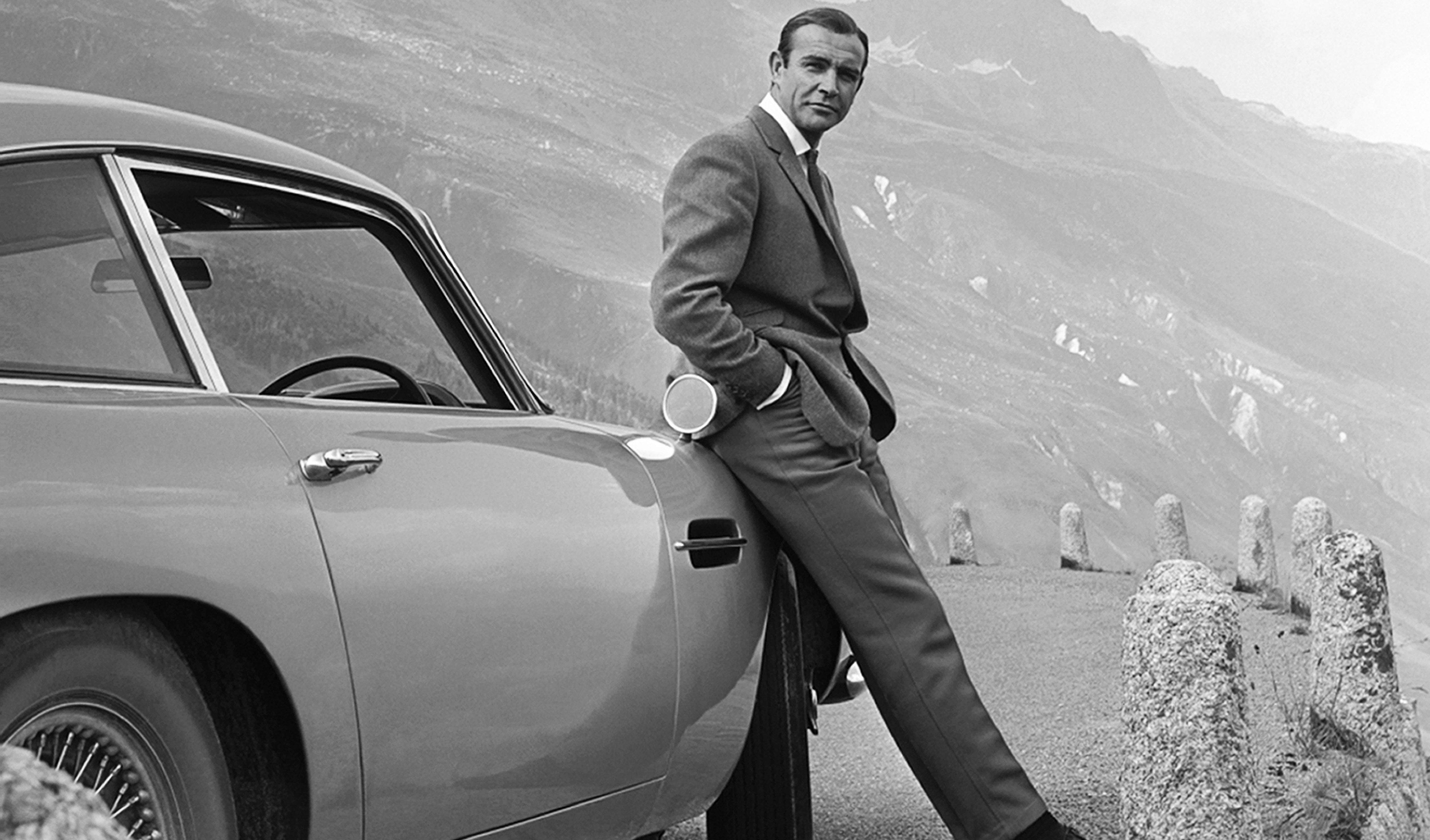

Bond's Aston Martin and Welsh rarebit: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 10, 2025

Bond's Aston Martin and Welsh rarebit: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 10, 2025Thursday's quiz celebrates pedestrian crossings and tests your language skills.

By Toby Keel

-

Scary sharks, the T-Rex and fabulous city views: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 9, 2025

Scary sharks, the T-Rex and fabulous city views: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 9, 2025Wednesday's quiz takes in restaurants, beautiful cities and more.

By Toby Keel

-

The beautiful island bridge, an otter's life and Churchill's TXT speech: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 8, 2025

The beautiful island bridge, an otter's life and Churchill's TXT speech: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 8, 2025Tuesday's quiz takes in cricket pitches, frittatas and more.

By Toby Keel

-

An architectural masterpiece, frog eyelids and Wordsworth's house: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 7, 2025

An architectural masterpiece, frog eyelids and Wordsworth's house: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 7, 2025Plus the longest bridge in Europe, all in Monday's quiz.

By Toby Keel

-

Hold the front page: How to find the ladybird hiding on this week's Country Life cover

Hold the front page: How to find the ladybird hiding on this week's Country Life coverDid you struggle to find the ladybird on this week's Country Life front cover? You weren't the only one.

By Rosie Paterson