King Charles III, by those who know him best: 'He has already changed the world'

Few realise the breadth and depth of Charles III’s interests and influence; fewer still can offer a meaningful answer to the question 'what is the King really like?'. But here, 10 friends of Country Life — all people who know and have worked with The King — predict he will be a magnificent and much-loved monarch.

Sir John Major: 'The King was so far ahead of received wisdom that he had to wait for it to catch up'

No monarch of our nation has been better prepared than Charles III. He has moved into the role with a sure touch and a deep understanding of all that will be required of him.

I do not claim to be an intimate of The King — and nor should any politician — but I know enough to be confident that, as the years unfold, he will become a very successful monarch and a much-loved one, too.

The nexus between the monarch and the Government is a sensitive one. It can easily be misunderstood and more easily misinterpreted. The monarch has every right to be fully informed about the actions and intentions of the Government, not least because each and every one of them will have an impact on the lives of those he or she serves.

Some critics have complained that — when still Prince of Wales — The King ‘lobbied’ ministers too forcefully; but, in my experience, such a criticism is woefully misguided. During the years I was Prime Minister, we met to discuss a wide range of issues and I found the meetings to be hugely beneficial. Yes, I was questioned about policy. And, yes, opinions were expressed. Yet I was never put under any pressure to follow any particular course.

The Prince invariably put his concerns to me fully and fairly — as I believe it was his duty to do — but I have never known him, or any other senior member of the Royal Family, step over the accepted line between Crown and Government. The question, as I saw it, was straightforward. Would I prefer an heir to the throne who highlighted a legitimate concern about what is happening in our country or one who showed no interest in how our people live and the problems they face? The answer to me was clear.

“Charles III is a man who believes in evolution, not revolution, cares about the common good and will seek to heal, not divide. During troubled and uncertain times, we are fortunate to have such a monarch.”

As monarch, there is no doubt The King will be circumspect, but I hope not too much so. I know of no prime minister who did not find the late Queen’s private counsel of immense value and that will hold true for Charles III as well. The King has a personal gift of empathy and an understanding of hardship. Both are sharpened by an acute sensitivity to others. It is that sensitivity that underpins his ability to sympathise with the ambitions, the hopes and the fears of people from all backgrounds. To be able to do so is a great strength for anyone in public life — and most especially in a monarch.

He has a talent for putting people at ease and, as did the late Queen, knows far more about how his people live than anyone — other than those close to him — might realise. From early childhood, The King was immersed in a world that put duty to others before self. He saw his mother’s own dedication until the very end of her life. He will be no less diligent.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

A modern man, he has often been well ahead of public opinion: on the encouragement of the young; on compassionate capitalism; on religious tolerance; on the built and natural environment; on agriculture; on climate change; and on so much more besides. Often, The King was so far ahead of received wisdom that he had to wait for it to catch up, which generally — albeit slowly — it did. Ideas he advocated that once were mocked have become orthodoxy.

The point is this: he leads opinion and does not follow it — nor is he influenced by fashionable chatter, for he has too much of his parents’ good common sense to do that.

I hope that The King will continue to talk — publicly as appropriate and privately when necessary — of the importance of community; of the natural world; of Nature; of compassion and caring; of his Armed Forces; and of his work for so many good causes. He should not be silent on issues that have been lifetime passions and upon which he is an authority.

Away from his duties, The King will still, I hope, find time for his private pursuits. His love of painting is known, but he also enjoys the theatre, notably Shakespeare. He loves listening to music — from classical to modern — and has an infectious sense of the absurd: it is no surprise that Monty Python films and Blackadder are among his comedies of choice.

Yet, perhaps, The King’s greatest passion remains that of creating gardens. His weekends at Highgrove and Birkhall were spent designing, landscaping, digging, planting and weeding — he does much of the physical work himself. No doubt, the gardens at Windsor, Balmoral and Sandringham will now receive equal attention. He will not waste his days of leisure. The King is a man with hobbies and interests aplenty, which is why he so easily finds a connection with all those he meets.

In a country and nation changing faster than is comfortable, The King knows our monarchy must continue to evolve. For centuries, there was a mystique around the Royal Family; but, over recent decades, public interest and modern media has pulled the curtain aside. Today, nearly every aspect of their lives is public property and nowhere is this searchlight more probing than upon The King and his immediate family. On any human level, this is intrusive and, at times, must be deeply upsetting, but The King carries the burden with dignity and fortitude.

Charles III is a man who believes in evolution, not revolution, cares about the common good and will seek to heal, not divide. During troubled and uncertain times, we are fortunate to have such a monarch.

On May 6, with The Queen beside him, we will move seamlessly from the Elizabethan to the Carolean age. As tradition dictates, bells will ring out and people will proclaim ‘God Save The King’.

From what we have seen thus far, I believe that proclamation will not merely be out of respect, but will — already — be out of genuine affection for His Majesty, King Charles III. Long may he reign.

Simon Jenkins: A lone voice in the architectural wilderness

THE then Prince of Wales was a man of many opinions. Some he kept to himself; others were mildly eccentric. But, on one subject, he made no attempt to conceal or restrain them: architecture. On this most public of art forms, he was unashamedly controversial. From the style of buildings to the nuances of town planning, he knew what he thought and would gladly take on any opponent, constitutional convention be damned.

He first broke cover in a speech in 1984. Still in his thirties, he had already declared his radicalism on alternative medicine, organic agriculture and community volunteering. Then came an invitation to speak on the 150th anniversary of the Royal Institute of British Architects at Hampton Court, an irresistible platform for his views on prevailing modernism. He tore up briefing notes and platitudes sent to guide him and disregarded pleas from aides who had wind of what he might say.

He duly launched a full-frontal attack on the profession there arrayed before him. Architects had, he said, ‘consistently ignored the feelings and wishes of the mass of ordinary people in this country’. They were trained to do one thing, ‘tear down and rebuild… for the approval of fellow architects, not for tenants’. He savaged their defiling of London, ‘once with one of the most beautiful skylines of any great city’. St Paul’s was to be ‘dwarfed by yet another giant glass stump better suited to downtown Chicago’. To the west, the National Gallery extension was ‘a vast municipal fire station… a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend’.

The dinner dissolved into near chaos. The guest of honour, the architect Charles Correa, refused to give his own speech. The National Gallery’s architect, Peter Ahrends, said the Prince’s views were ‘offensive, reactionary and ill-considered’. Norman Foster fumed and Richard Rogers complained the Royal Family ‘did not practise what they preached’. Yet press and public reaction sounded a quite different note. The reaction was overwhelmingly favourable. The Prince was no longer murmuring to plants, but talking robust common sense. Glass tower and carbuncle bit the dust.

In many of his controversies, Charles III tended to lapse into worthy abstractions. Not so in architecture. He, indeed, practised his preaching. Three years later, in 1987, he again took the stage, this time at Mansion House, to attack the City’s plan to replace the bleak post-war rebuilding of Paternoster Square north of St Paul’s with another ‘desecration’ of toxic Modernism. He compared the City fathers unfavourably with the Luftwaffe, which knocked down buildings ‘but didn’t replace them with anything more offensive than rubble’. He offered a plan of his own, drawn up by the neo-Classicist architect John Simpson. It was adopted and more or less built.

The Prince then turned to his own Duchy of Cornwall land outside Dorchester in Dorset, where he invited the favoured Léon Krier to build a completely new town. Traditional in both layout and design, Poundbury took some eight years of argument and near failure to get off the ground. The Prince never gave up. Still detested by Modernists, the estate has matured into a traditional mix of Cheltenham and Chipping Campden, its houses and flats hotly in demand. As if to rub salt into detractors’ wounds, in 1992, the Prince launched his Institute for Architecture in Regent’s Park. Together with other similar bodies, it morphed into The Prince’s Foundation, ardently committed to teaching the skills required for Classical and vernacular architecture.

Throughout his interventions, the Prince was adamant that he was doing no more than any private citizen in expressing an opinion and displaying his taste. He galvanised support for the lobbyists of SAVE Britain’s Heritage in rescuing Wentworth Woodhouse in South Yorkshire and in raising money to restore Dumfries House in Ayrshire. He would protest that he had no more power than the ‘opinion-formers’ who criticised him, which was a little naïve, given the breadth of his influence. He was ruthless in stopping a Brutalist replacement for Chelsea Barracks by intervening directly with its owners, the Qatari royal family.

The King’s most controversial technique was during the Blair Government, whose ministers he bombarded with scribbled ‘black-spider’ letters on anything that stirred his dismay. His attention span was notoriously short and the memos, when revealed under court order in 2015, were outspoken on topics ranging from military supplies to badger culls. As president of the National Trust, he once asked me as its chairman what we should do about the situation in Darfur. I had to explain that we had few members there. His concern was sincere, his application less so.

On architecture, one thing that stood The King in good stead was the simple fact that public opinion was overwhelmingly on his side. After his Paternoster speech, he received some 2,000 letters, almost all in approval. When, in 2009, Modernist architects, including Rogers, Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry and Lord Foster, declared his interventions ‘an abuse of power… and of democratic planning’, the press had only to look at their letters pages.

He was wholly aware that his opinions would have to be restrained if and when he was monarch. A Shakespeare fan, he knew Prince Hal’s warning on becoming Henry V: ‘Presume not that I am the thing I was… I have turned away my former self.’ His private secretary Sir Michael Peat said he was scrupulous of the need to ‘ensure he [was] not politically contentious or party political’. His campaigns as Prince were inevitably time limited and he wanted to get them off his chest.

The political establishment was plainly irritated to have a black spider crawling over its decisions. Equally, I sense that a large—albeit always mercurial—majority of The King’s subjects would be sorry if he was over-curtailed by constitutional convention. His had been a lonely voice. Architects had, for the best part of half a century, bullied politicians and planners into a highly partial view of how modern Britain should look.

For a public figure to give voice to a contrary opinion was thoroughly worthwhile. It would be sad to see it go.

Author and newspaper columnist Simon Jenkins FSA FRSL was editor of the ‘Evening Standard’ from 1976–78 and of ‘The Times’ from 1990–92. He also chaired the National Trust from 2008–14

Tony Juniper: ‘He’s already changed the world’

FEW of us these days are unaware of the momentous environmental challenges facing our world. Global heating, mass extinction of species, ecosystem degradation and the depletion of resources from fish stocks to soils are regularly in the news. It was not always like this, of course, with such questions relegated to the margins of society’s concerns for decades. That they are now on the agenda and mainstream is down to the work of visionary individuals who could see the need for change. Most prominent among them has been the former Prince of Wales, now Charles III.

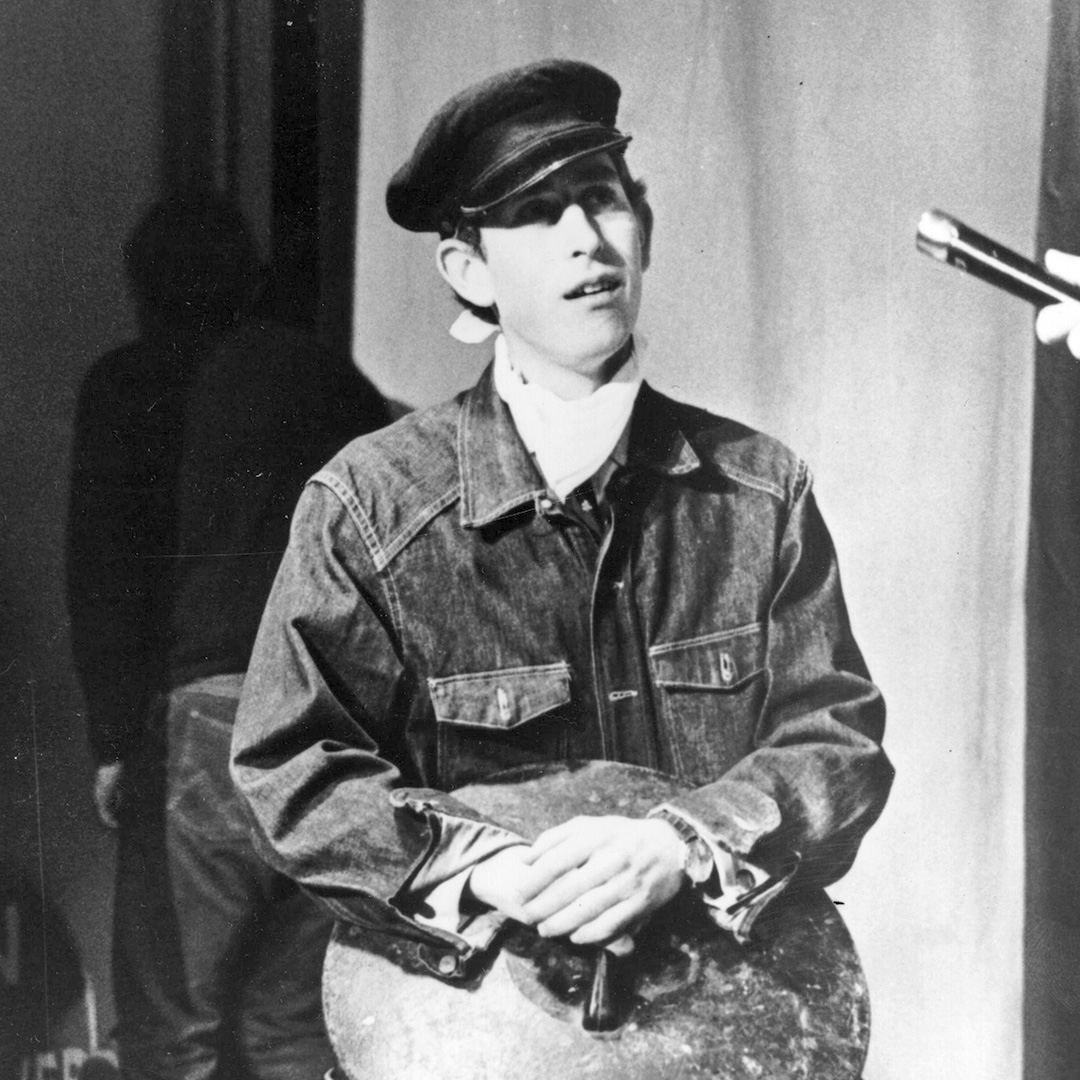

Long before celebrities drove Teslas and Greenpeace was a household name, in the days when organic agriculture was a fringe pursuit and few people had heard of the ozone layer, never mind climate change, there were very few voices speaking out for our planet’s future. It took a lot of courage to stand up and say what was happening, especially at a time when doing so often attracted ridicule. Back in December 1968, however, that is exactly what the 20-year-old Prince did, delivering his first environmental speech, at a conference about the future of the countryside in Wales.

It was the beginning of the most outstanding contribution on environmental issues from anyone anywhere in the world. When he was Prince of Wales, The King shone a bright light on pretty much every environmental question. His initiatives have raised the profile of tropical rainforests, the existential threat posed by climate change, the impact of excessive pesticide use, the need to protect food security through regenerative farming, the plight of the oceans and the opportunities arising from moves to sustainable fishing.

His advocacy has been based on advice from world experts, but also on seeing for himself the questions at first hand, reading vast quantities of material and participating in discussions, briefings and round tables. The breadth of his knowledge is as wide as the subjects upon which he has sought to galvanise action. In making progress, he has convened groups of influencers at the highest levels, including major global companies, governments, significant non-governmental groups and leading scientific bodies to find consensus on some complex and difficult challenges, such as the question of how to halt tropical deforestation. The initiative he originated on that subject, The Prince’s Rainforests Project (and the International Sustainability Unit that followed it) was influential in achieving significant outcomes, including at the Paris Climate Change Summit in 2015, which reached a breakthrough agreement that remains today.

His environmental work has, of course, been accompanied by interests and contributions in other areas, including education, health and architecture. Although, for some, this created the impression of a man who jumped from one issue to another, with a focus on buildings in the morning and sustainable farming in the afternoon, his 2010 book Harmony brought it all together. It revealed a golden thread that ran through all of his ideas, a unifying philosophy that sees Nature as being at the heart of human wellbeing and how the circular economy of the natural world must inspire the future of the human world.

He has helped multiple charities through being their patron, as well as setting up dozens of his own, including The Prince’s Trust and Business in the Community. Whereas some environmental advocates see people as the problem, he has always regarded them as the solution. His calls for sustainable farming centre as much on farmers as on soils, water and pollinators. His work for sustainable fishing has been much about fishing communities and his efforts to save the dwindling tropical rainforests embraced the future of the people who live there and from whose cultures came ideas that inspired aspects of Harmony, including the indigenous societies.

He worked in a tricky space for more than five decades, raising issues and making progress by bringing people together to forge solutions. He used his position with great skill, unswerving dedication and to great effect. Above the fray and with no axe of personal vested interest to grind, he fostered collaboration. He didn’t have to do what he did, but his personal calling was to make a difference and that is what he set out to do. His new role presents the challenge of finding an accommodation between, on the one hand, his longstanding mission to make progress on the most important issues facing our world and, on the other, the constitutional requirements that come with being head of state.

Since becoming King, he has already demonstrated something of what he can do, working with the Government to host two receptions at Buckingham Palace, bringing leaders together to encourage action. The first was in October 2022, just before the COP27 climate-change meeting in Sharm El Sheikh. The other took place in February, adding momentum in the wake of the successful Nature summit in Montreal at the end of last year. Although his personal voice will necessarily now be less prominent, these kinds of convening events are evidently compatible with his position as sovereign and more will follow.

Whatever the future may hold, however, our King has already changed the world, creating a legacy that historians will undoubtedly judge as going far beyond what might have been expected from the positions into which he happened to be born. If we do succeed in avoiding an ecological disaster later this century, part of the reason will be because of what he did for 50 years and more, driving a renaissance in ideas, raising awareness, bringing people together, celebrating good practice and supporting those who, like him, sought to make a difference.

Tony Juniper is an environmentalist, writer and the chair of Natural England

Christopher Price: Taking the rare-breed bull by the horns

FOR decades, the countryside and our rural communities have benefited from the great empathy and generosity of The King. Often behind the scenes, his support and action for communities, for wildlife and conservation, for food and farming and for rural heritage and skills have had a remarkable impact. In championing the under-represented and advocating for change, time and again he has shown a prescience that has only been recognised long after the fact.

When the then Prince of Wales became patron of the Rare Breeds Survival Trust (RBST) in 1986, many of our native breeds were at the bleakest point in their history. Our livestock and equines, bred for our landscape and habitats, were largely disregarded, out of fashion and, in some cases, kept going by only a handful of smallholders and farmers. As a whole, mainstream farming neither understood nor appreciated the irreplaceable value of native breeds’ characteristics.

The King’s foresight in celebrating and promoting those traditional breeds has been borne out and I am pleased to say that many more people are now catching up.

The skill, knowledge and passion with which His Majesty has supported RBST’s work over the past four decades has made an invaluable and very practical contribution to the breeds’ survival. The Prince’s Countryside Fund’s generous support helped us greatly expand the RBST’s work, not least in the aftermath of the horrors of foot-and-mouth disease, as well as our recent Equine Conservation Project and Farm Park schemes. Without fanfare, our patron has readily committed his own animals for our breeding programmes to help secure vulnerable, irreplaceable genetic bloodlines. He has quietly given a home to new herds that RBST has formed to save some of our very rarest breeds.

At other times, fanfare has been put to good use: I was honoured to visit Cotswold Farm Park alongside Charles III as he encouraged visitors to the network of RBST-approved farm parks when they were finally able to reopen after the first covid lockdown.

In this receipt of inspiration, I join RBST members of all ages. When a rare Boreray lamb was presented to the then Prince of Wales as a 70th-birthday gift at the Royal Cornwall Show in 2018, its proud breeder, Jowan Bobin, was only 15 years old. He has since completed an agricultural course and now runs a sustainable farm in Cornwall with Boreray sheep, Oxford Sandy and Black pigs and Golden Guernsey goats. It is the type of farm with potential to play a key role in a future for the countryside where high-quality food production goes hand in hand with the natural environment and multiple societal benefits. I feel sure His Majesty would approve.

RBST’s patron is a superb figurehead for the native breeds’ cause, but he most certainly leads by example, too. The educational farm he has created at Dumfries House is home to vital rare livestock and poultry breeding groups, from Vaynol and White-bred Shorthorn cattle to Castlemilk Moorit sheep and a variety of our priority poultry breeds, such as the Scots Dumpy. This work is not only improving the outlook for future generations of these rare breeds, it is also giving thousands of visitors an unforgettable experience of sustainable farming. The breeding programmes there have been successful in boosting breed numbers, geographic distribution and genetic diversity. The selection of breeds, comprising those in desperate need of help, but which would also have the right characteristics to thrive on the estate, reflects our patron’s encyclopaedic rare-breed knowledge and farming experience.

This knowledge and passion were brought to bear at Highgrove, too. His Majesty gave the nation a fantastic exemplar of the leading role native livestock and equine breeds should play in a sustainable approach to food production and land management, from Gloucester and Irish Moiled cattle to Large Black pigs and Cotswold sheep, and many more. Equine breeds are not overlooked, with two rare Suffolk Punch heavy horses showing the world their strength and skill. I look forward to seeing what His Majesty will create as he welcomes more breeds to Sandringham (‘Farming for our futures’, May 19, 2021).

The King’s talents for seeing sustainable farming in the round and bringing people together were at the heart of the Coronation Meadows project to celebrate the 60th anniversary of Elizabeth II’s coronation. The partnership between Plantlife, The Wildlife Trusts and RBST ensured the role of native-breed grazing was showcased as part of the action to reverse the decline of biodiversity.

Another example of this ability to bring people together for common good is the local-produce conference held at Highgrove in July 2016, where RBST and Slow Food UK joined forces to help develop supply chains for native-breed farmers by engaging with the hospitality sector. The then Prince of Wales gave generously of his time to talk with speakers and guests, providing great encouragement for all those working for a strong future for native breeds.

His Majesty’s skill in facilitating and supporting these types of connections and collaborations will be invaluable in the country-side’s challenging transition to a future in which food production and a modern rural economy need to work in harmony with environmental improvement and conservation.

We are living through an era of intense debate over land-use policy and it can be a struggle to find common ground between special-interest groups. As rural communities respond to each new crisis or opportunity, we desperately need leaders with an understanding of these nuances and who see things in their longer-term context. As we mark the coronation of Charles III, I have no doubt His Majesty will continue to employ his knowledge, skill and dedication to great effect for the people of the countryside, for the future of our landscapes and wildlife and in support of our native breeds.

Christopher Price is chief executive of the Rare Breeds Survival Trust and a former director of Policy and Advice at the CLA. He is also chair of the Wildlife and Countryside Link Agriculture working group and vice-chair of the Uplands Alliance

Baron Chartres: Our defender of the faith

MOST people in their early seventies have retired, yet our King is only just embarking on the most arduous period of his national service. He has been in the public eye, subjected to intense scrutiny, from his earliest years. His image was on the savings stamps that many of us collected when we were young. Now, his profile will soon be in circulation on everyday stamps and coins.

He represents an institution with a long history. In May, The King will be anointed in a coronation ceremony that incorporates many of the symbols introduced in 973 by St Dunstan when he crowned Edgar the Peaceful in Bath. The 10th-century rituals owed much to European precedents, but, now, they are a unique survival in Europe.

Such continuities are an important thread in a narrative that allows all those who dwell in these islands to say ‘we’. Of course, the changes have been profound. No one today could seriously echo the words of Shakespeare’s Richard II, who declared: ‘Not all the water, in the rough rude sea can wash the balm off from an anointed king. The breath of worldly men cannot depose the deputy elected by the Lord.’

It was in the 19th century that British monarchs finally surrendered the last vestiges of actual political power. Monarchs became part of a dignified national pageant. Their duty was to hallmark the realm of common values that lie beyond the struggle that is proper to political partisans. Sovereigns and their families were to give the constitution a human face and provide a focus for personal loyalty.

Yet for modern monarchs, at a time of increasing social and generational polarisation, the role of unifier is a complex and exacting task. Although it would be intolerable for the occupant of the throne to become a colourless cipher, the institution would probably not survive a self-indulgent monarch who only did the bare minimum.

This is the context for the immense achievements of our late Queen’s reign, recognised by the outpouring of affection and respect that followed her death. Our new King will interpret the role differently, but he has inherited the self-discipline and the capacity for hard work that formed the foundation of Elizabeth II’s 70 years on the throne.

Bertie, Queen Victoria’s eldest son, grew up as the role of monarchy was changing. Although he became beloved as Edward VII, it cannot be said that as Prince of Wales he brought very much lustre to the institution.

By contrast, we have had many years to appreciate the renaissance prince who is now our King. The sheer range of his interests and activities is astonishing. He has come to the throne at a time when the bonds that unite our society are under strain, when our planet seems to be on a trajectory leading to ecological degradation. In both these fields, he has been a pioneer and his involvements have been sustained, not those of a dilettante.

When, in 1976, Prince Charles completed his service in the Royal Navy, it was a time of record inflation and unemployment and he used his navy severance pay to fund a number of community initiatives. By 1983, having learned from the success of some of the initial projects, The Prince’s Trust launched an ‘Enterprise Programme’ and, within three years, 1,000 young people had been helped to start a business. By September 2020, the trust was able to announce that its work had supported one million young people.

The Prince of Wales also used the extraordinary convening power of the monarchy to work with companies to improve their impact on wider society. He organised visits by CEOs to alert them to contemporary problems, from urban homelessness to the challenges facing hill farmers in remote areas.

Charles III has been a consistent advocate for rural life and responsible farming, not least in his many contributions to COUNTRY LIFE. Renaissance princes were celebrated not only for the breadth of their interests, but also for their personal proficiency in the Arts. Likewise, The King, when not engaged in official duties, is a talented painter in the exacting medium of watercolour. He is a discerning and generous patron of music and musicians, as exemplified in the coronation.

The source of the energy that sustains such varied enthusiasms can perhaps be found in The King’s marked spiritual awareness. Albeit rooted in the Church of England, his sympathies and spiritual curiosity are wide. He will promise, in the coronation, to be ‘defender of the faith’, but he is, at the same time, aware of the vital contribution that faith communities of all kinds make to charitable work and social cohesion. His appreciation of Islam and his support for beleaguered Christian communities throughout the world are well known. Once again, his knowledge and sympathies are not those of a dilettante, but of someone who has a place of prayer in his garden at Highgrove, to which he frequently resorts.

The Renaissance that began in the Italian cities of the late Middle Ages was characterised by a revival of ancient wisdom that widened horizons and opened the way to a renewed Christian humanism. In today’s very different world, we can rejoice in a King who is inspired by the wisdom that is old, but always fresh.

Lord Chartres is a former Bishop of London and Dean of HM Chapels Royal

Margaret Casely-Hayford: The King of Arts

From his interest in Shakespeare to his love of music, via his support for diverse communities, our monarch has a true appreciation of the Arts

ACROSS the varied areas in which I work, I draw a sense of strength that our new monarch has influence and a love of the Arts. As the chair of Shakespeare’s Globe, I know that The King has an enormous love of our lead in-house writer—and frequently quotes him. What is wonderful for us is the continuity of the interest, not only in the writing, but also in our structure, which uses form and techniques Shakespeare himself would recognise. The Globe is an embodiment of heritage skills I know The King holds dear—although at a reception thrown for members of the Commonwealth diaspora, the then Prince of Wales entreated me to ‘do something about those bum-numbingly uncomfortable seats!’ (We do provide cushions for delicate bottoms.)

As a trustee of the Radcliffe Trust—which supports this country’s cultural heritage and craft sectors and champions contemporary composers—I was delighted to learn that The King’s great passion for music led him not only to request traditional works for the coronation, but also commission some wonderful new pieces, including one by Shirley J. Thompson.

But there’s more to The King than a ‘mere’ appreciation for the Arts: his ability to connect on a personal and individual basis is astonishing and he has been an incredibly supportive ambassador of charities such as ActionAid UK, which aims to eradicate poverty by focusing on the rights of women and girls. As Prince of Wales, he was an active patron from 1995, talking passionately about ActionAid’s work and visiting several projects, including in Brazil, Sierra Leone and Uganda.

We live in sensitive times and there are many who are vocal about not being monarchists. To me, a constitutional monarchy is a critically important element of our establishment: where governments rightly change in response to democracy, the monarchy is a constant, yet is held in check. It doesn’t retain unbridled power but, simultaneously, connotes necessary stability. It is one of my abiding memories that every Prime Minister has said that working with the late Queen was not only a joy, but that they learned from her, rather than the other way round. That is a symbol of the strength and knowledge that comes from continuity, which also holds significant cultural importance, because memory is a crucial part of who we are as individuals and, therefore, as a nation.

Historic memory isn’t always easy and we must work to address some structural imbalances. It’s worthy of note that Baroness Patricia Scotland, Secretary-General of the Commonwealth, was asked to speak first at the Queen’s funeral service. This, to me, was a wonderful symbol of the importance of the Commonwealth both to her late majesty and her family. Monarchy is as much about this country as it is about others with which it has an historic relationship and, for me, Charles III’s reign can be a symbol of that understanding and hope.

Margaret Casely-Hayford is a lawyer, businesswoman and the chair of Shakespeare’s Globe

Ralph Beckett: My kingdom for a horse

IT is 42 years since The King’s stint as an amateur jump jockey concluded and 18 years since his distinguished career as a polo player came to an end. Although Charles III didn’t ride a winner in his six outings on a racecourse, he did finish second twice. Allibar got him off to a promising start, with second place in an amateur chase at Ludlow. Sadly, the horse came to an early demise, collapsing one morning when walking home from exercise with trainer Nick Gaselee. Replacement Good Prospect was not very big and notably short-necked. Perhaps a less than ideal conveyance for an amateur, he unseated The King twice in five days, famously in the Kim Muir at the 1981 Cheltenham Festival.

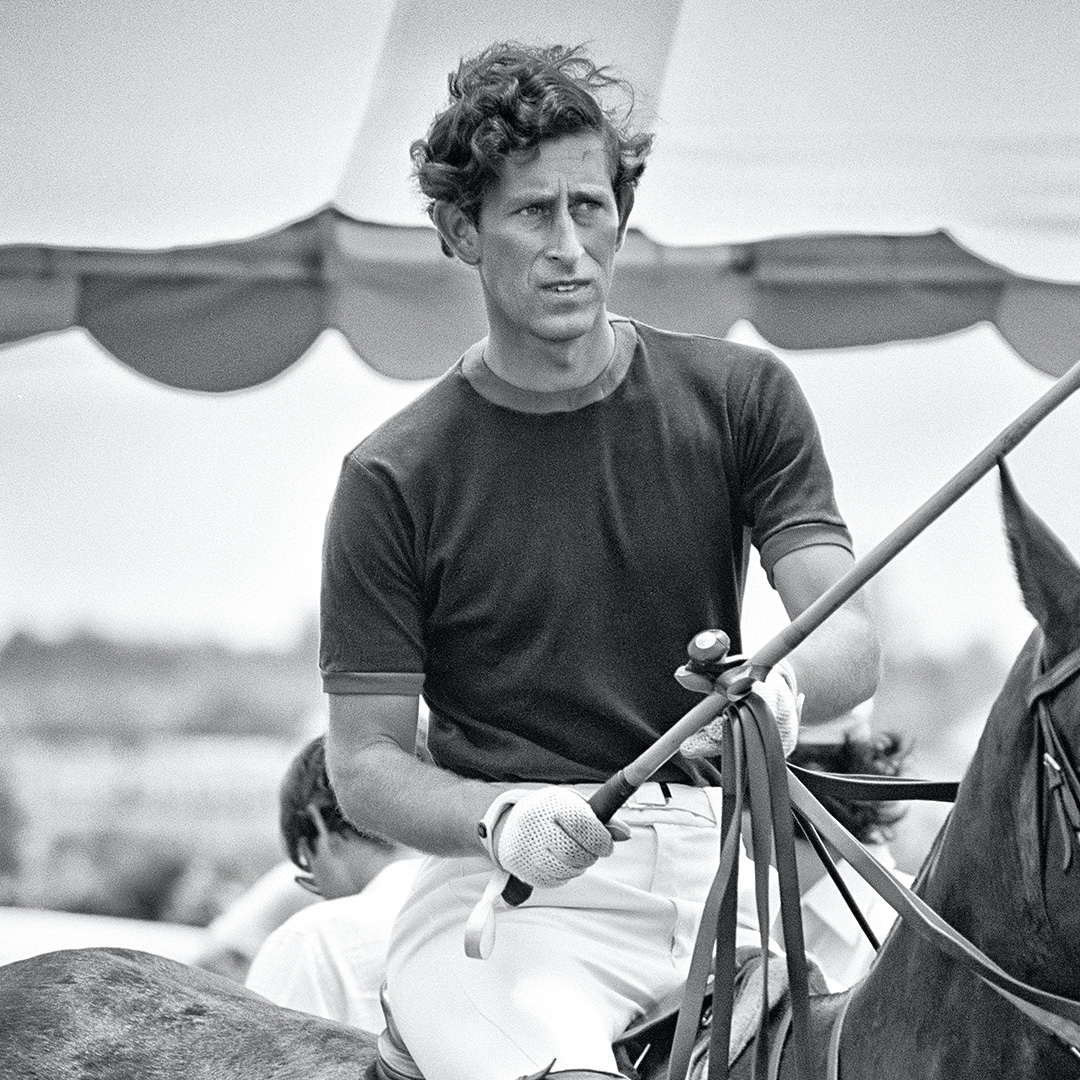

By contrast, Charles III’s polo career was as auspicious and as long as his race-riding spell was short. He played his first match at 15 years old in a team captained by his father, the Duke Of Edinburgh, and went on to play 17 times for Young England. In 1979, he scored all four goals in a 4–2 win for the Royal Navy over the Army in the Rundle Cup and, in 1981, played for England against Spain. He reached a handicap of four goals, making him a top-10 British player of his time and at least twice as good as either of his sons. He was considered a classic player, whose favourite position was at back in defence.

The Prince retired from serious competition just after his 57th birthday, with a list of injuries that included a broken arm, concussion and being hit by a ball in the throat, which resulted in him losing his voice for 10 days. From then on, he played only for charity, raising £12 million in the process.

A keen follower of hounds before the 2004 ban, he was a regular visitor to anywhere that tested horse and rider, particularly the Shires, and was well known for going route one in the huntsman’s pocket, regardless of how formidable the obstacle. Indeed, if you look hard enough among one of the hedge bottoms away from Willoughby Gorse, in the Quorn Monday country, there is apparently a tiny plaque with the inscription: ‘The Prince Of Wales broke these sticks.’ As a countryman, he is popular with farmers, pro-hunting or otherwise, wherever he visits.

The new Queen, too, was an avid follower of hounds from a young age, starting with the Southdown (now part of the Southdown & Eridge) in Sussex. In the 1970s, she shared with her mother steeplechasers that were trained by Fulke Walwyn at Lambourn in Berkshire, the most notable being Menehall, who won at Aintree. With her first husband, Andrew Parker Bowles, she bred numerous chasers and polo ponies. Blessed with a terrific eye, she is well known by friends and family for recognising a three year old if she had known it as a foal.

It is not surprising, therefore, that, as a wedding present, Elizabeth II gave the then Prince of Wales and his bride a Sadler’s Wells mare named Supereva. Her first progeny arrived as a yearling at Whitsbury, Hampshire, in the autumn of 2007. Named Royal Superlative, she belied her name, but won a maiden at Chepstow, making all up the stand rail under Jack Mitchell. There followed a succession of less than talented, but victorious horses, including tiny Carousel, who was one of our first winners on moving to Kimpton Down, Superciliary (a gorgeous, but soft type) and Ravenous (small, yet hardy), until decent handicapper Pacify showed up. He was much the best his dam produced and we had a lot of fun with him, although he did disappoint on the day that mattered most—at Royal Ascot in 2016.

There’s little doubt that the Royal Studs will continue to produce homebred winners on a regular basis, with decent prospects such as three-year-old Slipofthepen, which won at Kempton recently and is now quoted as a leading contender for the Derby, plus there are a number of promising types that have gone into training this year as two year olds. With the significance of the horses running in joint ownership not to be underestimated, both The King and The Queen’s enthusiasm for the Sport of Kings is readily apparent—hence, their future patronage of the great game is assured.

Ralph Beckett is a leading trainer of Flat racehorses at Kimpton, Hampshire

Dylan Jones: Monarch of the trend

THE KING has served as a brilliant role model for sustainable fashion and style and has been a lifelong advocate of good old-fashioned British tailoring. For that alone, he should be celebrated. I have always gone out of my way to champion Charles III as a style icon, because he’s become a talismanic figure in the fashion industry. He has developed the ability to fly the flag for British tailoring and craftsmanship, looking good in the process.

His classic looks include the safari suits of his youth (once famously worn with a short-sleeved, baby-blue safari shirt, a pair of tight chinos and some Helmut Newton-style riding boots), the traditional double-breasted jacket, which he completely subverts by jamming both hands into its pockets, the almost-bling signet ring (which he is supposed to pass on to William because of its Prince of Wales crest) and, of course, his love of tartan.

My all-time favourite Charles III look is the one he sported in the late 1970s when he was visiting Canada. He looked like a cross between John Wayne and Pee-Wee Herman, in a western suit (in an extremely modern shade of urgent pink) with a check shirt, a bootlace tie and a superb white 10-gallon hat. Then there was the time he sported an egg-yellow Hermès top (complete with cartoonish ‘Happy Hermès’ logo), a blue chambray shirt and a pair of skintight white jeans that left almost nothing to the imagination. He was dressed for the polo, but could just as easily have been going to a nightclub. He also appears to wear his blazer everywhere, regardless of whether or not it’s appropriate. Indeed, his equerries used to joke that he wore his favourite blazer in the bath.

Nonetheless, he takes all this stuff terribly seriously. I was once at one of his receptions at Dumfries House when His Majesty was unusually late. ‘I’m terribly sorry,’ he said with a smile, ‘but I changed my cufflinks three times before I came down.’

Whenever he is asked about his style, however, he likes to downplay it by being as self-deprecating as his position allows. ‘I think I’m a bit like a stopped clock,’ he’s fond of saying. ‘I get it right twice every 24 hours.’

Sustainability might be fashionable these days, but The King has been banging that drum—the same old drum, mind, with recycled skins—for decades. It’s ironic that he was pilloried for years for his obsessions, but he is now at the forefront of a modern movement that celebrates the old almost in spite of the new.

A few years ago, I spent a considerable amount of time with the then Prince of Wales, shadowing him for a magazine article, and he was nothing if not passionate in his espousal of his beliefs—and, obviously, still frustrated that industry and government often only pay lip service to sustainability.

Although he has decried fashion for fashion’s sake, he has nonetheless been something of a style icon. Ten years ago, when the British Fashion Council asked me to create Britain’s first fashion week devoted entirely to men, there was only one person I wanted to launch it and that was the Prince of Wales. His ability to celebrate the traditional with the anarchic chimed with my idea of what a fashion week should look and feel like, especially in Britain, celebrating the traditionalism of Savile Row on one hand and the entrepreneurial spirit of outspoken young designers on the other. Even then, the fashion industry believed in his own particular brand of style. Only Charles III could have convened all the warring Savile Row tailors, only he could have intrigued the young, just-out-of-college designers and only he had the pulling power to drag Vivienne Westwood, Tom Ford, Tommy Hilfiger and Paul Smith down to St James’s in the middle of the afternoon. And I remain convinced that it was his patronage that made the event so immediately successful.

The King makes you feel proud to be British. He looks British, sounds British and carries himself with a swagger that, in other hands, could look unnecessarily bullish or embarrassingly Mr Beanish. He is a cool-looking dude, which is what we expect him to be. I don’t think we like it when our politicians are too well-dressed (some of us distrusted Tony Blair because of this, in the same way that some look at Rishi Sunak as too much of a fashion plate), but we want our royals to wear that mantle. I certainly do.

Personally, I’ve always been a fan of The King. Not only have I enjoyed the fact that he tends to speak his mind, but, even from a young age, I thought his outspoken manner was actually rather smart. Where his mother was all about decorum and being silently quizzical, he always had more of his father in him—namely an ability to look aghast at strange developments in modern life that he didn’t like.

Plus, of course, he always dressed like a king. A flamboyant king, for sure, but a king all the same, even when he was only a prince.

A journalist and author, Dylan Jones was editor of the UK version of the men’s fashion and lifestyle magazine ‘GQ’ from 1999–2021

Dame Fiona Reynolds: Cometh the hour, cometh The King

A KING who warned of the carbon and Nature crises years before the rest of the world woke up to them. A King who is as comfortable in a farmhouse kitchen, a shepherd’s crook by his side, as in a royal palace. A King whose hands are scarred with the toil of hedge-laying, yet soft enough to enfold those who have received public awards, from knights (and dames) to recipients of British Empire Medals. A King who has helped countless young people take hold of their future, at the same time as persuading some of the world’s largest businesses to embrace sustainability. A King who loves nothing better than a quiet hour in a beautiful garden, where he impresses the local expert with his horticultural knowledge. And a King with a fine eye for architecture and design, from the vernacular to the unashamedly grand. In short: a King with a keen sense of beauty and how fundamental it is to our lives.

In this time of contested priorities and short-term politics, isn’t this exactly the kind of King we need? For although public policy is horribly siloed and seems ill-equipped to deal with a pressured economy and a succession of short-term crises, our King understands the bigger, long-term picture and has an unerring instinct for what motivates and sustains the people of the UK.

He knows our country intimately and understands it better than most. Over decades, he has visited every corner of the British Isles, taking time to acquaint himself with the spirit of each place and bringing delight as a royal visitor. Often, when I was working for the National Trust, I would receive a discreet telephone call seeking space in a busy visit for a spell of spiritual refreshment in one of our beautiful gardens or houses. We were always delighted to make this happen.

And he remembers: people, details, dates and stories. Years later, in a conversation about something entirely different, The King might draw an analogy or remember an anecdote that can only have come from such a fleeting, but clearly meaningful experience.

He cares. The joy of repeated, out-of-the-limelight visits to the Lake District—a landscape he loves—were jolted into another dimension by the horrors of foot-and-mouth disease in 2001. He cheered us on as we did all we could to save the Herdwick sheep from destruction from contiguous culling (today’s flocks being direct descendants of those shepherded by Beatrix Potter; Native breed, January 11). As the restrictions were lifted, he was among the first to visit the farms and their occupants who had been so terribly afflicted by the disease. He did the same in so many contexts: after floods and disasters he was always there, quiet, compassionate and completely genuine, understanding what people needed; not grandstanding, but offering real empathy, drawn from his own insights into the realities of people’s lives.

In Harmony, perhaps The King’s most personal articulation of his credo, he wrote: ‘This book offers inspiration for those who feel, deep down, that there is a more balanced way of looking at the world, and more harmonious ways of living.’ If that was true in 2010, it is more than ever now, as the implications of our failure to control the speed of climate change or reverse the decline of Nature have become ever more apparent.

Our world, our country and the places we live in and love are ecosystems of interconnected networks, underpinned by Nature and natural resources, but heavily influenced by humans. As The Economics of Biodiversity (the Dasgupta review into the economics of Nature) showed us, sometime in the 1950s human activity started to outstrip its ability to regenerate. The world is a tapestry of woven threads, which are now beginning to break.

Our King may rarely speak publicly on these issues now, as he did in the past, but make no mistake, we have already heard what he has to say. If ever we needed a role model to lead us to a better, more sustainable future, it is there in the form of our King, Charles III.

Dame Fiona Reynolds was formerly Master of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and director-general of the National Trust. She is now the chair of Governors at the Royal Agricultural University, Cirencester, and the author of ‘The Fight for Beauty’

Patrick Holden: ‘The world’s greatest convener’

OTHERS have highlighted The King’s many achievements; he is surely one of the most inspired and influential human beings on our planet. I believe his lifelong service—to humanity and the natural world—has rarely, if ever, been equalled. However, having known him for 40 years—initially through our shared interest in sustainable agriculture—I would like to share a personal perspective. I recall the excitement I felt in 1982, when I was first invited to meet the then Prince of Wales, who was considering putting his green farming principles into practice at Highgrove. I was on the list of guests because I—as were many there that day—was an early adopter of this way of farming, having left London in the early 1970s to set up a community farm in west Wales, which marks its 50th anniversary this year.

As the son of a doctor, who grew up in London and attended mainly state schools, my background contrasted significantly with his. Nonetheless, I immediately felt a strong sense of affinity. This was partly due to our interest in organic farming, but I suspect that he, like me, had also been influenced by some kind of global shift of consciousness in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Perhaps Jamie Oliver was right when he described him as ‘a bit of a hippy’—I definitely sensed he was a fellow traveller.

I can’t remember exactly what I said, except that I was tongue-tied and overwhelmed, muttering something about my experience of milking cows and organic dairy farming. I think there was some kind of mutual recognition, because we stayed in touch.

After deciding to go ahead with the organic conversion, a small parcel of land was chosen out of sight of the general public, in case it went wrong; back then, organic farming was seen as fringe, unworldly and decidedly not mainstream. Typically, the Prince persisted, converting the dairy farm and then the entire 1,700-acre estate to organic. Initially, this was not widely appreciated by the establishment. Subsequently, however, the Highgrove Farm and gardens became a place of pilgrimage. They offered a ‘seeing is believing’ experience to tens of thousands of visitors, including a small, but highly influential, group of farmers, policymakers, academics, food companies, philanthropists, environmentalists, celebrities and the media, as word got out that what he was doing was of long-lasting significance.

In my role as head of the Soil Association and, subsequently, the Sustainable Food Trust, we benefited greatly from this capacity to convene others on issues about which he was passionate. He did not attend meetings and we often joked that, if he had, delegates might have been distracted and learned less. As a result, the ‘Highgrove alumni’ now numbers more than 1,000 influential people, from all over the world, who have witnessed the positive impacts of the practical application of sustainable and Nature-friendly farming principles at landscape level. Indeed, I believe that The King is universally acknowledged as the greatest and most influential champion and advocate of sustainable food and farming.

Having been such a seminal influence for change, any normal individual might have been tempted to stop there and rest on his laurels, but not the future King. There is no doubt that his work at Highgrove led to what I consider to be one of his most important contributions to humanity, namely the publication of Harmony in 2010. The book details a new way of looking at our world and includes the observation—as The King has expressed in speeches—that ‘we are Nature’ and, by extension, ‘what we do to Nature we do to ourselves’. It stresses the need to work in a more interconnected way and that, in future, food production must operate in harmony with Nature through ‘land sharing’, as it did until the 1950s.

Known for his vision and intuition, the extraordinary breadth of his interests and knowledge, spanning history and culture, the Arts, faith communities, literature, music and the environment, The King has many hidden qualities, too. These include loyalty, humanity and vulnerability, but also courage, tremendous self-discipline and an incredible work ethic—how many of us go back to our desks after dinner in the evening? This discipline, finding expression in his determination to respond to as many letters and emails as possible has resulted in him perhaps being one of the greatest letter writers of our time.

Then there is his understanding and compassion, especially for animals. I was once in a car with him in rural Romania when we came across an accident, in which a horse, driver and cart had come off the road and ended up in a ditch. We were the first on the scene and, despite the anxiety of his close protection officers, he leapt out of the car and calmed the horse to make sure that no one was injured.

This sensitivity towards animals is matched by his remarkable ability to put people at ease and his extraordinary capacity to talk to each person he meets, leaving them feeling seen, heard and perhaps touched by an exchange in which he says something pertinent and meaningful that stays with them.

He likes to laugh, too. I have been reduced to tears by his anecdotes and mimicry, but never at the expense of others. I suspect that side of him—which goes back to his love of Spike Milligan and the Goons’ 1950s radio shows—is a release for all the huge responsibilities he has to reconcile in his role as King.

There is no doubt that his extraordinary dedication to service connects to his awareness, since childhood, of his destiny eventually to become King. Now that he has acceded to the throne, his role must rightly restrict his interventions. However, I doubt that this restraint will prevent him from continuing to be an important influence. This is because, during his long apprenticeship, he has earned such enormous respect from international leaders. Consequently, he has become, without question, the world’s greatest convener. Nowhere has this been more evident than in the Sustainable Markets Initiative (SMI). This was launched by the then Prince at Davos in 2020, inspired by his conviction that only if the world’s business community is fully engaged will it be possible for humanity to act at sufficient speed to harness the necessary resources to avoid catastrophic climate change and the breakdown of ecosystems.

As a participant in two SMI task forces, I have witnessed The King evoke a sense of higher purpose in world leaders, which has forged new friendships and trust. These new bonds are vital at this precarious time when, only through collaboration, will we pass on our planet in a fit state for future generations.

I know I speak for many when I say that His Majesty is a truly remarkable human being, dedicated to lifelong and selfless service, for which I believe we all have cause to be deeply grateful. God bless The King! Long live The King!

Patrick Holden is an organic dairy farmer, campaigner for sustainable farming and co-founder of the Sustainable Food Trust

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.