When it comes to heritage development, the conservation officer is king. We need more of them

A lack of funding and expertise is having a detrimental effect on our listed heritage. To survive, these buildings need to adapt, and to adapt, these buildings need more people who understand what makes them special.

If our planning system has a heritage footsoldier, it is surely the conservation officer. These are the individuals who are meant to know about the listed buildings of the area in which they work and who can offer informed views not only about what makes them important, but how they can be appropriately adapted and developed.

When dealing with reasonable changes and demands on the part of owners, moreover, their role ought to be that of an expert facilitator, polishing and improving what has been proposed in heritage terms. Whatever their views on a particular project, it should also be possible for them to explain their opinions clearly so that their concerns can be understood and addressed. Athena has experience of many projects in which heritage conservation officers have performed exactly these positive roles. That’s not always the case, however, and she is conscious that there are clear patterns as to what tends to go wrong and why.

On the part of owners, it’s worth bearing in mind that the involvement of a conservation officer ought to begin early. To state the obvious, this can prevent the frustration of developing ideas that are clearly doomed to disappointment on heritage grounds. It can also establish a sense of mutual understanding and a consciousness of the specific interest and physical circumstances of the place in question. The ideal is for their first-hand experience of the property in the company of the senior professionals involved, but, unfortunately, that’s easier said than done.

Cuts within local authorities have left planning teams woefully under-resourced and with specialist expertise seriously eroded. It’s hard to put a figure on the change because it’s so uneven, but there are areas where there is presently no in-house heritage expertise at all. Historic England, meanwhile, will only involve itself with the most important listed buildings.

For hard-pressed planning teams, particularly those with little experience, it can be easier to follow rules to the letter and object to proposals outright than risk making a mistake. In such cases, it can be instructive by way of a response to visit other local properties and find precedents for what is intended; private owners and businesses occupying historic properties — say a country-house hotel — within the same locality are sometimes held to strikingly different standards.

Dealing with the planning system is complicated and it can be deeply frustrating. In seeking to improve it, however, it is important not to confuse an excess of red tape with inadequate resources. Both cause obstruction and paralysis, of course, but the former enforces rules of no utility or purpose, whereas the latter makes onerous and inefficient the observance of regulations that have merit. If we had more heritage conservation officers with more time and greater latitude of action, we might all be a great deal happier than, as at present, when we have too few.

Athena is Country Life's cultural crusader. She writes a column every week.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The law of unintended consequences is teaming up with Britain's latest tax rises — and it'll hit our historic houses hard

Country Life's cultural commentator Athena takes a closer look at last week's budget and foresees trouble ahead.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

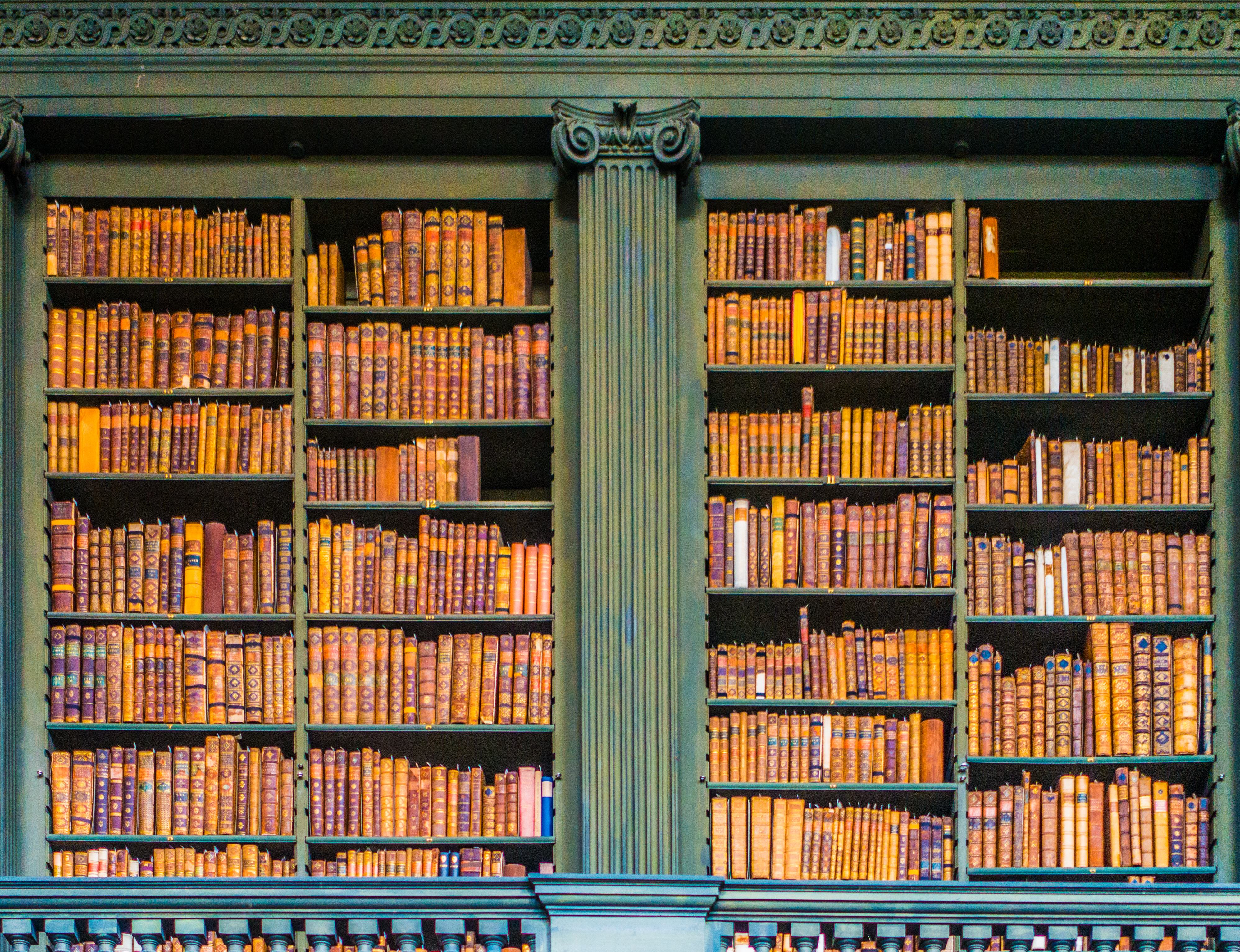

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life