Jonathan Meades on Anthony Burgess: 'The encyclopedia in his head was like the internet'

Jonathan Meades reviews a new selection of Anthony Burgess’s literary journalism, gathered from previously uncollected reviews and essays from throughout his career.

In his introduction to this absorbing and scrupulously chosen collection of Anthony Burgess’s literary journalism, Will Carr quotes a 1972 interview in which the novelist talks about the benefits of book reviewing. For Country Life, ‘I had to review books on stable management, embroidery, car engines – very useful solid stuff, the very stuff of novels’.

He might have qualified that as ‘my novels’. For one of the many characteristics that set this giant of a writer apart from his contemporaries was his engagement with the everyday and his detachment from what passes for ‘the literary life’. Quite how simulated that detachment was is moot.

However, it is undeniable that a formidable knowledge of just about everything is evinced in his fiction. He was too modest when he claimed that all a novelist needs is ‘imagination and a children’s encyclopedia’. The encyclopedia in his head was like the internet. To spend any time with him was to be dazzled by his sheer volume of knowledge and his (oddly humble) desire to keep adding to that volume, to be a specialist in all fields, trivial meadows included. Burgess would have agreed with Housman’s dictum that ‘knowledge is precious whether or not it serves the slightest human use’.

"His best work belongs to the Nabokovian tradition – inventive, shocking, brutally poetic and proddingly boastful about the very words it is composed from"

Most of his preoccupations manifest here will come as no surprise to his devotees: Joyce, the perpetual futility of using high literature as the basis of films and the coarse chimera of synergy, slang and its lexicographers, the crassness of TV in 1993 (when, by today’s standards, it was at least watchable), the disgusting paltriness of censors, the brilliance of V. S. Naipaul and William Burroughs, the usefulness of pornography, the joy of blasphemy and the inadequacy of prose (and poetry) in comparison to music, where several lines can be played simultaneously.

Many of the pieces suggest that Burgess adhered to Wilde’s paradox in The Picture of Dorian Gray, that criticism is a form of autobiography, an ever-accreting bildungsroman marked not by events, but by thoughts, spiritual moods and imaginative passions. Criticism is, in Burgess’s case, an autobiography of multiple contradictions.

The most fundamental contradiction is the constantly implicit debate about the nature of fiction. Ought it to be opaque, like that of, say, Nabokov, where the style is, as Burgess has it, a ‘character’, or merely a narrative in the manner of Somerset Maugham or Priestley? Burgess lurched between the two, although there can be no doubt that, with the exception of The Malayan Trilogy, his best work belongs to the Nabokovian tradition – inventive, shocking, brutally poetic and proddingly boastful about the very words it is composed from.

Dessicated browning newsprint is seldom as entertaining as this dense and generous collection of enthusiasms, expressions of self-doubt and civilised muscularity.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The Ink Trade: Selected Journalism 1961-1993 by Anthony Burgess, Edited by Will Carr, is published by Carcanet, £19.99

Jason Goodwin: ‘Memories fade. Gavin was right: buildings outlive us all and they’re each memorials. They should not be allowed to disappear’

Our columnist remembers Gavin Stamp, the architectural critic, historian and campaigner.

Where to live near London: top commuter stations

Commuter heaven is an efficient train that's far out enough to get a seat, but near enough to get you

Girls in pearls on horseback: British event riders in Country Life

British beauties mad keen on eventing.

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by HRH The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.

-

From California to Cornwall: How surfing became a cornerstone of Cornish culture

From California to Cornwall: How surfing became a cornerstone of Cornish cultureA new exhibition at Cornwall's National Maritime Museum celebrates a century of surf culture and reveals how the country became a global leader in surf innovation and conservation.

By Emma Lavelle Published

-

Jaecoo 7 SHS: Can you really get a luxury SUV for £35,000?

Jaecoo 7 SHS: Can you really get a luxury SUV for £35,000?The Chinese automaker Jaecoo lands on UK shores with the 7. We take it for a spin around Scotland and the north of England to see if the hype is real.

By Charlie Thomas Published

-

'It may be vain to think that the past was a cleaner, quieter and kinder place, but it felt pretty decent when you knew your GP and your GP knew you, and milk in glass bottles was delivered every morning'

'It may be vain to think that the past was a cleaner, quieter and kinder place, but it felt pretty decent when you knew your GP and your GP knew you, and milk in glass bottles was delivered every morning'Carla Carlisle is homesick for the olden days, when we didn’t know we had it so good.

By Carla Carlisle Published

-

Patrick Galbraith: We are a brilliant and terrible species who messed it up a long time ago — and that means we have to do things we don't want to

Patrick Galbraith: We are a brilliant and terrible species who messed it up a long time ago — and that means we have to do things we don't want toOur columnist laments the painful decisions on culling wild animals which he argues have to be taken if we're to manage the countryside and maintain biodiversity.

By Patrick Galbraith Published

-

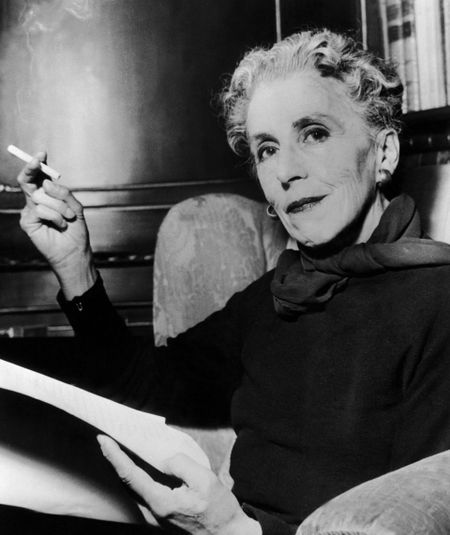

'From the first page until the last, I was in another country, another world... It was like falling in love'

'From the first page until the last, I was in another country, another world... It was like falling in love''There is beauty and there is poverty, order and corruption' — Carla Carlisle on Karen Blixen and Kenya.

By Carla Carlisle Published

-

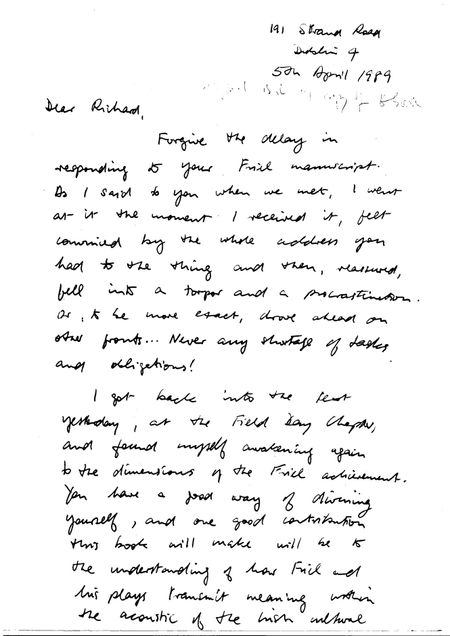

Carla Carlisle: 'Seamus Heaney deserves a sainthood, as well as his Nobel Prize'

Carla Carlisle: 'Seamus Heaney deserves a sainthood, as well as his Nobel Prize'Carla Carlisle applauds The Letters of Seamus Heaney and shares how she couldn't wait until Christmas to devour the collection from the late Irish poet

By Carla Carlisle Published

-

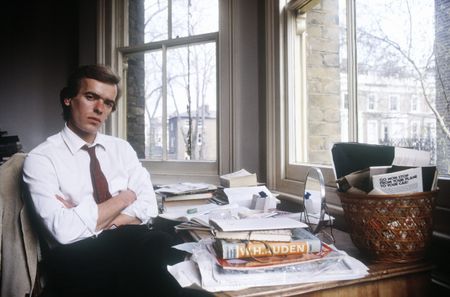

Carla Carlisle on Martin Amis: The 'passionate, graceful, fierce' writer who scared us, challenged us, and brought us understanding

Carla Carlisle on Martin Amis: The 'passionate, graceful, fierce' writer who scared us, challenged us, and brought us understandingCarla Carlisle pays tribute to the late Martin Amis, who died last month.

By Carla Carlisle Published

-

Carla Carlisle: 'Edit your one and precious life. Prepare for Judgement Day. Do it Now.'

Carla Carlisle: 'Edit your one and precious life. Prepare for Judgement Day. Do it Now.'Carla has been having a bit of a New Year clear-out — albeit one which started last August, and which is NOT going particularly well...

By Carla Carlisle Published

-

Jason Goodwin's books of the year 2022

Jason Goodwin's books of the year 2022Our columnist Jason Goodwin shares the books that have entertained and enlightened him this year.

By Jason Goodwin Published

-

'By the time I reached chapter seven I was nauseated by the sheer volume of stuff I owned'

'By the time I reached chapter seven I was nauseated by the sheer volume of stuff I owned'Jonathan Self's chance encounter with a book shifts the way he sees his belongings... but how long will his urge to declutter last?

By Jonathan Self Published