Opinion: Why small family farms should be the future of agriculture in Britain

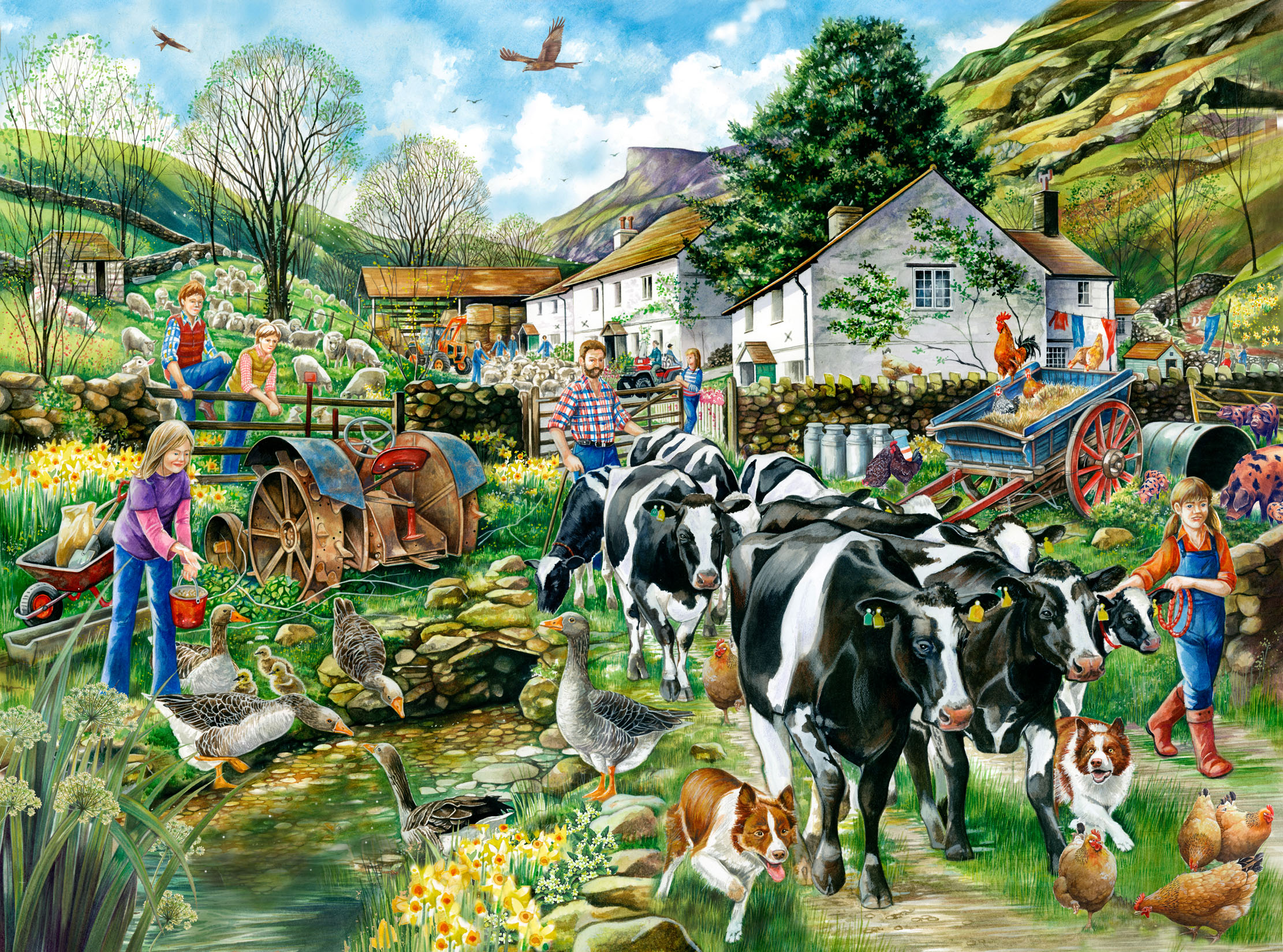

Many aspects of farming are expanding — and not always in a good way. Jason Goodwin argues that it needs re-balancing, with a return to multiple small family farms, neighbourly cooperation and a bolstering of the local community.

A debate at this year’s Oxford Farming Conference considered the motion that ‘the demise of the family farm has been greatly exaggerated’. After the stats and stories, the house — comprising many of the industry’s movers and shakers, of all ages — voted the motion down by 2 to 1. The family farm, they believed, was dying on its feet. However, neither the people who thought it was dying, nor the people who thought it was still flourishing, considered the death of the small family farm to be a good thing at all.

It isn’t hard to see why family farms might be in crisis. With property prices sky high and many tax advantages for people with money to invest in farmland, it has made sense for a lot of small farmers to flog their land, sell off the farmhouse and retire, dividing the proceeds between their children. The farmer who stays in the game adds that land to his, but looks for economies of scale, relying on contractors. Behind him or her, a barrage of agronomists, salespeople, seed merchants, vets, scientists and retail barons helps to ensure that a bare 7p of every £1 of produce returns to the farmer who created it. The farmer is always running to stay still.

Farming’s creeping tendency toward bigness is baked into our way of running policy. It is in the nature of big governmental bureaucracies to engage with other big organisations to formulate big policies that cover large areas of life and the land. The result is a country bereft of people, from where giant farms truck produce to join huge and complex supply chains, heading to big supermarkets, as their field margins are managed for eco-subsidy.

From a smallholding in Dorset that overlooks the sea, Jyoti Fernandes runs the Landworkers’ Alliance, the aim of which is to represent small and family farms. She argues fiercely against the idea that the family farm is dying, but agrees that it’s all about policy. Small farmers attending Defra meetings may find, for instance, that all the talk is about exports. ‘We don’t need export opportunities,’ she points out. ‘We need to open up our own domestic markets. Small farms are interested in strong domestic opportunities.’

These exist, and they urgently need expanding. The 20th-century retreat from the land has impoverished us as a nation. Plenty of British children (and some adults) can’t say if carrots grow on trees and believe that sheep are killed for their wool. Some of them are hungry. As fewer people work on the land, farmers find themselves getting blamed for a range of real and imaginary sins by avocado-gobbling drivers of electric SUVs, prompting their shy retreat from local life. Hunting is banned by townies with no sympathy for or understanding of the countryside. In villages now, as well as in towns and cities, people rely on supermarkets and are cut off from ideas of seasonality or basic food production.

"Nothing could gladden the eye like a countryside of small farms and smallholdings, in a patchwork of tiny fields, with a shack or a caravan or a Hobbit-house every few acres"

Getting more people working on the land isn’t only good for those people in terms of their health and wellbeing. It’s good for people around them — and for the earth itself. More people living on, and off, the land means a livelier rural scene. Local farmers are on call to stem floods, tow cars or lend machinery to the village fair. They use the village amenities, the shop, the post office and the pub, where people chat and form communities. Families living on the land and populating villages provide customers to the church’s round of funerals, christenings and marriages, as well as harvest suppers.

Smaller farms may be more efficient — or not; the only evidence is that efficient farms are more efficient than inefficient ones, regardless of size. Mary Durling, a smallholder in Dorset, points out that her range of lamb and vegetables sell locally. ‘I’m producing a mix, not concentrating on one crop that needs to be shipped to a distant distribution centre,’ she observes. Small farmers can keep more of their profit and eat more of their own produce.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Direct selling to the public helps them keep the value of what they produce, but the wider benefits are legion. In market towns with a thriving food scene, the farmers educate their customers; they advocate for their way of doing things, demystify the process and the product and give urbanites a glimpse of what the countryside produces — and how.

Then there is the issue of food security. When Covid struck, the lucky ones among us were able to go without the supermarket altogether, by relying on farm shops and local food, driving a rise in meat boxes and suchlike. Small family farms producing food that gets processed — slaughtered, picked or packed — locally are doing their bit for the climate and society. We live in an unstable, uncertain world and farming resilience has to be extended. If that means challenging the supermarkets and their supply chains, so be it. The alternatives are already there. A recent report says that Britain’s farm shops employ 25,000 people, with sales totalling £1.4 billion — and most of them expect business to grow, not shrink.

The trend so far is away from the small producer, but policy can change. The stopper is straightforward: high land prices, sustained by subsidy, tax and investment rules and planning. What we need is not only more small farms to join the thousands already on the land, or more families to join the 150,000 or so people already working out there, but hundreds of thousands of farmers.

Organisations such as the Ecological Land Cooperative try to bring cheap or free marginal land into cultivation by ‘stewards’, whose commitment to agriculture is overseen by the group and who enable small farmers to build and live on their plots. We need thousands more smallholdings, their owners supplementing their income with outside jobs, by specialising, by needing less in the first place. Bring on the micro-dairy, the mushroom grower, the bee-keeper’s orchard, the salad producer.

William Cobbett, the farmer, politician and polemicist who believed in local distinctiveness, saw beauty where he saw rural prosperity: well-fed children, hard-working adults and a pig in the sty. He would have railed against a green sward divided by blown-out hedgerows, visited twice a month by a contractor with a heavy machine. Just as there’s no finer sight than an allotment garden, so nothing could gladden the eye like a countryside of small farms and smallholdings, in a patchwork of tiny fields, with a shack or a caravan or a Hobbit-house every few acres, with polytunnels, sheep shelters and pig arks.

Perhaps we should begin where Cobbett wanted us to start two centuries ago, G. K. Chesterton a century later or the Sustainable Food Trust in our own age. Even that hoary compendium of common sense, the Bible, cries: ‘Woe unto them that join house to house, that lay field to field, till there be no place, that they may be placed alone in the midst of the earth!’

The best fertiliser, says an old proverb, is the farmer’s footprint. If we are to have decent countryside and proper food, we must have more feet on the land, bare or booted. This means more people and fewer massive systems. We can either have change at a pace we command, or we may yet have it by default. Many people think our current way of life is doomed to fail and that a civilisation that doesn’t understand where its food is coming from is ripe for collapse.

It happened in ancient Rome, it happened to the Mayans and to the ancient Mesopotamians. All of a sudden, the whole house of cards collapses. One moment, everyone is ordering the Mayan equivalent of frozen strawberry milkshakes for immediate home delivery or wolfing down Rome’s answer to deep-fried animal protein from a chicken shack, and the next they are lucky to be pushing seeds into the earth with a stick.

Jason Goodwin: Supermarkets sell 10,000 different things, but it turned out we hardly need any of them

Jason Goodwin's local farm shop has it all — including prices which ring up in historic dates.

Jason Goodwin: 'What gets lost will be forever lost, whereas pylons, cars and trains may be rendered obsolete'

Jason Goodwin muses on economics, Stonehenge and social media.

-

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotels

Why British designers dream up the most desirable hotelsWhen it comes to hotel design, the Brits do it best, says Giles Kime.

By Giles Kime Published

-

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication

The five minute guide to 'The Great Gatsby', a century on from its publication'The Great Gatsby' sold poorly the year it was published, but, in the following century, it went on to become a cornerstone of world literature.

By Carla Passino Published