The true story of St Valentine, his legend and legacy of love

Whatever the truth of the real St Valentine, the middle of February has been a favourite time for lovers since records began. We take a look at the curious history of St Valentine, and how an ancient martyr came to be remembered as a champion of romantic love.

In modern times, St Valentine's Day is more closely associated with cards, chocolates and commercial gain, but it has not always been the case. Although the story of the saint and the origins of the feast day are clouded by myth, February 14 has long been celebrated as the day of lovers.

The earliest version of the story dates back to ancient Rome and the pagan festival of Lupercalia. Shepherds outside the city walls waged a constant battle against hungry wolves and prayed to the god Lupercus to watch over their flocks. Every year in February, the Romans would repay the god's vigilance with a festival, which doubled as a celebration of fertility and the onset of Spring. Newlywed women would be whipped by februa (strips of goat skin and the derivation of our word February) to purify their bodies in preparation for childbirth.

One of the highlights of Lupercalia came on February 14 with an erotic tribute to Juno Februata, the goddess of feverish love (the equivalent of Cilla Black). The names of maidens were drawn at random by young men and the resultant couple would become partners at the feast and even for life.

"The bishop was executed on February 14.... On the eve of his death, he sent a passionate letter to his beloved, signed simply 'your Valentine'."

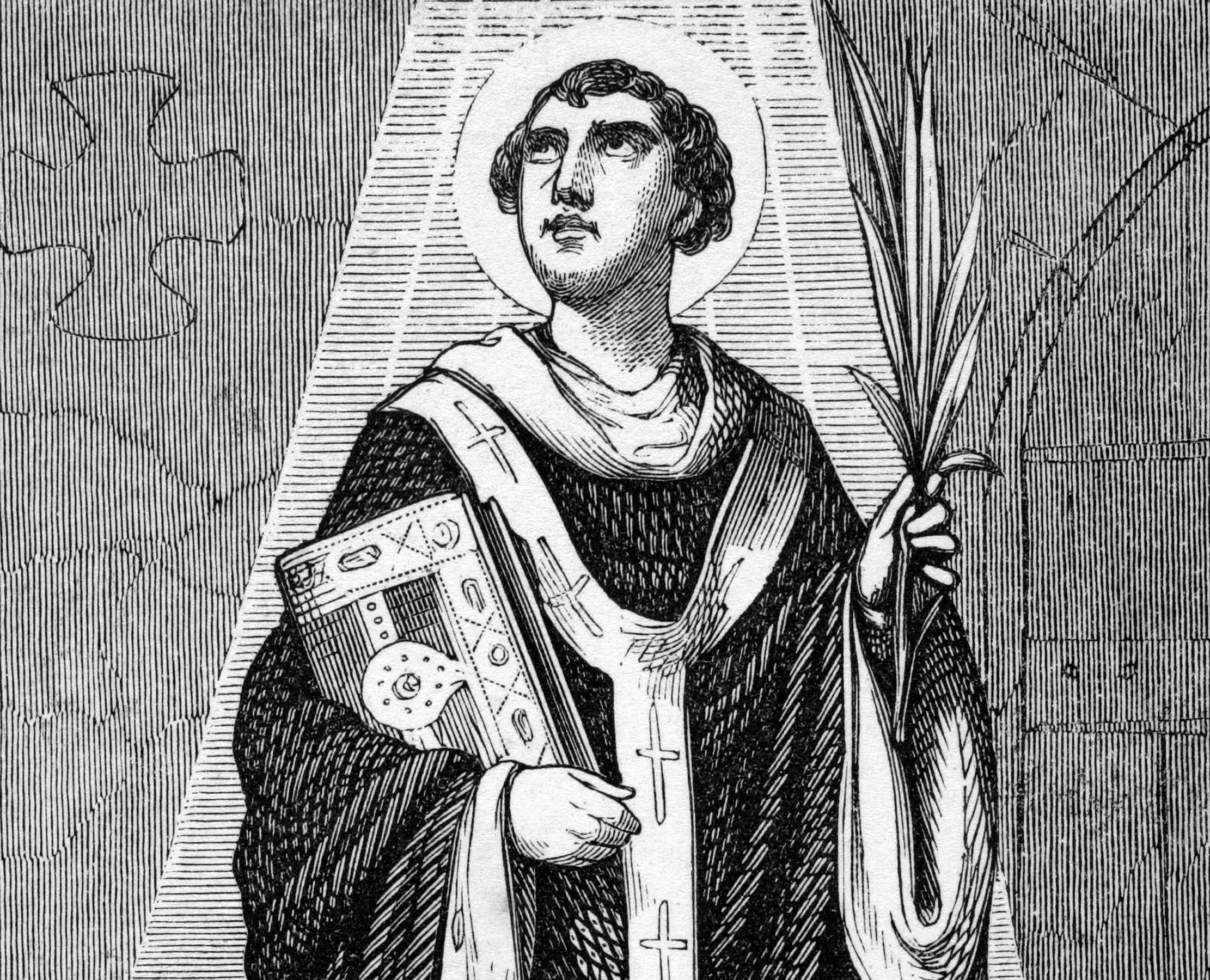

The festival was extremely popular and lasted for centuries. After Constantine had christianised Rome, the Church tried to clamp down on pagan activities and Lupercalia, with its lurid temptations, was an obvious target. Pope Galasius, in the 5th Century, needed to find a suitable replacement for the wolf god Lupercus and chose a bishop who had been martyred 200 years previously: Valentine.

The emperor Aurelius had imprisoned Valentine in 272 AD for continuing to marry Christian soldiers, despite royal decree (Aurelius needed them to fight his wars). In prison, the bishop cured his jailer's daughter of blindness and the pair fell head over heels in love (quite literally 'love at first sight'.) Ultimately, their desires were frustrated as the bishop was executed on February 14 the following year. On the eve of his death, the condemned man sent a passionate letter to his beloved, signed simply 'your Valentine'.

Whatever the truth, the intention of the Church to curb Lupercalia only served to extend the tradition of celebrating true love in the middle of February and any later attempts to take away the romantic angle proved unsuccessful. It was the mediaeval English who would take the saint's day to a new level and guaranteed its future. One theory is that the word 'valentine' comes from the Normanga latin, meaning gallant or lover of women, which further enriched the romance of Valentine's Day. (According to etymologists, the letters v and g were once used interchangeably.)

Roses such as Constance Spry — David Austin's first-ever 'English' rose — have long been the flower of choice for Valentine's Day. Picture: Charles Quest-Ritson

Young ladies in England would write the names of prospective lovers on slips of paper, before rolling them in clay and placing them in a bowl of water. Whichever name rose to the surface first, would be their Valentine. In Scotland, names were drawn from a hat three times and if the same name appeared each time then marriage would follow. Of course, it was possible to increase your chances of finding the right name. The name of your Valentine was then worn on your sleeve for the remainder of the day.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

It was not just a day for humans, either. In the Middle Ages, it was believed that birds chose their partners on St Valentine's Day and poets often rejoiced in the link between lovebirds and lovers. According to the historian Peggy Robbins, many superstitions were related to birds seen by maidens on Valentine's Day. If she saw a blackbird, she would marry a clergyman; a goldfinch, a millionaire; a redbreast, a sailor; a crossbill, a quarrelsome man. A wryneck would condemn the poor lady to the fate of an old maid.

To improve their chances of finding true love, single girls could run round a church twelve times without stopping; lay bay leaves sprinkled in rosewater on their pillow; or even eat a hard-boiled egg at midnight, shell and all. A lady approaching old-maid status was advised to try all of the above.

The popular act of handing a red rose to your lover was made famous by Robert Burns' poem 'My love is like a red red rose' although the Scot, who was well-versed in the ways of love, was not talking about Valentine's Day. Indeed, true lovers will wear the yellow crocus over their heart, in dedication to St Valentine. It is thought he once drew two strangers together with a single crocus and they never parted again.

Yellow Crocus — the other flower of love...

The Europeans are not the only ones to celebrate love, fertility and purification at this time of year. Since 767 BC, the Japanese city of Inazawa has held the Shintu ritual Hadaka Matsuri, the Naked Festival, in February to purify its people for the year ahead.

It is a great honour to be chosen as the naked man, but he has his work cut out. He is shaved from head to toe and sent to the Kounomiya Shrine at the other end of the city. But 9,000 sweaty men in loin-clothes try to stop him, as each competes to touch and grab the naked man. In doing so he will absorb their bad luck and evil deeds. When the naked man does finally arrive at the shrine, having endured a whole day at the mercy of the crowd, he is dressed in robes and chased out of the town to rid the town of all its evil.

Further west, on February 15 this year, (the first Full Moon of the Chinese New Year) young couples in Hong Kong will meet to celebrate Yuen Siu, the Spring Lantern Festival. Everyone holds lanterns to avoid being snatched by ghosts and spirits swooping down and snatching them away. The lanterns carry riddles and sweet nothings, similar to Valentine messages, and the young men and women play games to find out who will be their partner.

In the past, it was the one day of the year when a woman could come out, with a chaperone, and be seen by eligible men. In the days when women's feet were bound, it was often the one time when she could appear in public with unbound feet.

On the other side of the world, in the island paradise of Tahiti, the Love Marathon is run every year on the Ile de Moorea. One thousand athletes race round crystal blue lagoons and tropical forests, receiving pineapples, papayas, mangos and coconuts en route to speed their way. That evening the party begins and with the sweet scent of the tiare flower in the air, Vahinedancers, wearing the traditionalmore(grass skirts) and cache-titi (strategically-placed coconuts) sway to the beat of Tahitian drums.

The legacy of St Valentine has survived long after his death. There was such an uproar over his execution among the Christian community in Rome, that the authorities had to bury his body quickly to avoid a riot. But three of his followers found his body and took him to Terni in Umbria, where he is perfectly embalmed in the Basilico de S Valentino.

Young lovers still travel to the tomb to ask his blessing and the city throws a month long festival in his honour every year in February. Nowadays, his memory has been hijacked by card sharks and florists, but the ancient tradition of proclaiming love on February 14 remains.

This article was first published in Country Life in 2004.

Curious Questions: Why do we say it with flowers?

Post-Valentine's Day, Martin Fone takes a look at the true meaning behind flowers, decoding what each individual bloom says about

Country Life is unlike any other magazine: the only glossy weekly on the newsstand and the only magazine that has been guest-edited by His Majesty The King not once, but twice. It is a celebration of modern rural life and all its diverse joys and pleasures — that was first published in Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year. Our eclectic mixture of witty and informative content — from the most up-to-date property news and commentary and a coveted glimpse inside some of the UK's best houses and gardens, to gardening, the arts and interior design, written by experts in their field — still cannot be found in print or online, anywhere else.