Jason Goodwin: 'There must be a moral here, but I can’t work out what it is'

Our Spectator columnist ponders the highs and lows of picture hanging.

There are some tasks that, undertaken together, foster conjugal harmony. They may not be the same for everyone. Kate’s sister and her husband, for instance, enjoy sailing and are bound by the salt tang of the wind and the dangers of the deep, as well as the prospect of winning the Fastnet Race: the very ingredients that would, if mixed into our marriage, almost certainly dissolve it.

We like picture framing instead. Over the years, Kate has amassed an extraordinary number of frames of all shapes, sizes and patterns, which have accompanied us from house to house to the gentle tinkling of breaking glass and the cracking of joints.

Some time ago, Harry very sweetly stacked them in the cellar to make room for his drum kit, and they began growing damp and mouldy. Meanwhile, the plan chest is full of watercolours and sketches, geometric mandalas and prints. Some of them were done by us, the rest gradually acquired from auctions, charity shops, exhibitions, inheritances and friends.

On a recent weekend, we pulled them all out and began to fit frames to pictures. It was fun, like matchmaking. We took empty frames to the glazier, who cut new glass. I assembled a battery of pliers, oddly shaped hammers, clean cloths, a Stanley knife and a steel ruler, and sequestered the kitchen table. We picked apart grimy old frames: glass to the sink, mounts and backing boards to be dusted and brushed, rusty pins and greasy hanks of old string to the bin. The dreary artworks they had originally displayed were pulled out and set aside – feeble watercolours by amateurs long since dead, cheap and garish prints from a more pious age, meretricious reproductions and dull sketches. There is, I’m afraid, a hierarchy of quality in art.

In their place, we set old prints and the artwork of gifted friends. We swapped mounts around, did fiddly things with sheets of watercolour paper and sliced surrounds to fit, before clapping everything back together with pins and passe-partout, new eyes looped with bright brass wire. The pictures sparkled behind the shiny glass-like jewels, leaning on the floor at the foot of the kitchen dresser.

It was good to do right by the pictures, to lock them snugly into frames, protected from buffeting and spillages. Some had reminded us of people we loved, or forgotten places and old times, and framing them was like kindling a fire on the hearth. It brought order out of chaos, tidied up some loose ends. It was like doing all the washing-up the morning after a good party and we worked away so companionably that, like Donne’s lovers, ‘Our eye-beams twisted, and did thread/Our eyes upon one double string’.

Yet there are some other tasks, when undertaken together, that sow only discord and disharmony – and, sadly, picture hanging is one of them. Standing for 10 minutes with outstretched arms, holding a picture flat against the wall, moving it up, moving it down, slightly to the right and back again, piles irritation on annoyance. The hook is an inch too low. The wall is made of powder. The pictures look crowded, or are the wrong height, or in the wrong sequence. You hit your thumb with the hammer again and drop pins off the ladder, stepping back into the glass you so painstakingly fitted earlier, and your helpmeet has become a savage pedant who can spot a variation from 10 paces and calibrates distances between frames by thousandths of an inch.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You can’t have picture hanging without picture framing, yet one leads to misery and the other to happiness. There must be a moral here, but I can’t work out what it is.

-

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?

What's a 'wellness village' and will it tempt you back into the office?The team behind London's first mixed-use ‘wellness village’ says it has the magic formula for tempting workers back into offices.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

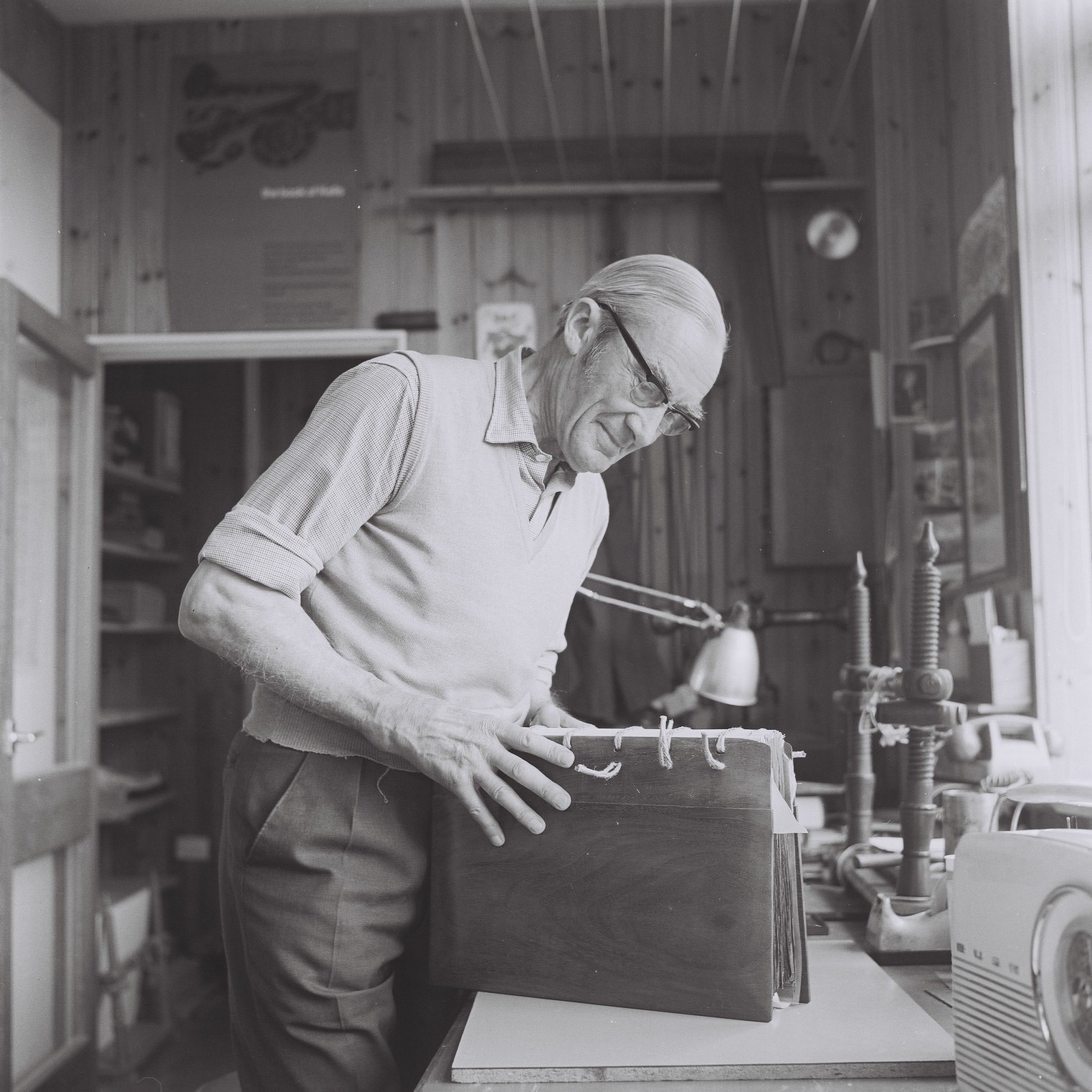

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani