Jason Goodwin: Forget what you were told at school — history is simply a cracking story that happens to be true

The education system did its best to put Jason Goodwin off history, but he came through unscathed — and thank goodness too, otherwise he might not have been able to recommend these summer reads.

Years ago, anyone wanting to study history at university used to be given a prophylactic called What Is History? by Professor E. H. Carr. History, he taught, was what anyone said it was. Nobody could ever be properly objective and any historian claiming to be fair-minded was either a liar or a fool.

Carr had been a Nazi sympathiser at the outbreak of the Second World War, but transferred his admiration from Hitler to Stalin. The engine of progress, he claimed, was class struggle, leading to the workers’ triumph and the overthrow of bourgeois individualism.

The master pattern had been set out in excruciatingly vague detail by 19th-century German philosophy, so it only required the evidence to be clinically assembled by intellectuals like Prof Carr. Otherwise, like the Hungarian Marxist György Lukács, he agreed that ‘history becomes a collection of exotic anecdotes’.

I sincerely hope so. A few of us have been reading the latest history books for The Historical Writers’ Association Crown Awards and many of them contain splendid exotic anecdotes. Last year’s winner, Leanda de Lisle’s White King, reconsidered Charles I by drawing on loving letters from his wife, Henrietta Maria.

This year, just in time for your late-August holiday, we have a long list of 12 books; absorbing stories that illuminate places and periods we might wish to know better.

Sue Prideaux’s biography I Am Dynamite! shows Friedrich Nietzsche as an original and even amusing thinker, who later sank into madness and whose writings were repackaged by his virulently anti-Semitic little sister.

Helen Rappaport’s The Race to Save the Romanovs addresses a nagging question: why, given every warning, did the Tsar and his family stay in Russia, to be brutally murdered in the cellar at Yekaterinburg? Did George V really let them down and could more have been done to save them?

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Fast forward 60-odd years and Oleg Gordievsky is losing faith in the system that has brought him to the Soviet embassy in Copenhagen as a KGB agent. Ben Macintyre’s The Spy and the Traitor tells how he becomes a British double agent and of his hair-raising escape.

Midnight in Chernobyl by Adam Higginbotham is another nail-biter: a forensic investigation into the nuclear disaster that epitomised the shortcomings of the Soviet empire and hastened its end. Eleanor Herman’s witty and gruesome The Royal Art of Poison ends with some hair-raising anecdotes about Russian state assassination today.

Secrets are kept across the ideological divide, too, in Daniel Immerwahr’s How to Hide an Empire: A History of the Greater United States. Secrecy turns sleazy in The Real Lolita, brilliant sleuthing by Sarah Weinman.

Two books we loved are about Japan. The title says it all in Naoko Abe’s ‘Cherry’ Ingram: The Englishman Who Saved Japan’s Blossoms. Between the wars, Ingram single-mindedly rekindled Japan’s reverence for cherry trees. How the Japanese came to lose it in the first place might concern Christopher Harding, whose Japan Story deals with that country’s unexpected responses to westernisation and the modern world.

Some of our books describe another island. The Five: The Untold Lives of the Women Killed by Jack the Ripper by Hallie Rubenhold takes a fresh line on the Whitechapel murders. Nick Barratt writes a lively portrait of medieval England in The Restless Kings: Henry II, His Sons and the Wars for the Plantagenet Crown and Kate Hubbard’s fascinating Devices and Desires: Bess of Hardwick and the Building of Elizabethan England deals with an astonishing Yorkshirewoman, her mania for construction, marriage and the Elizabethan Wonder House.

Rather than a scientific treatise that distorts the evidence to fit a theory, I prefer a good story that also happens to be true. That, I think, is history.

Credit: Alamy

Jason Goodwin: On wardrobes, spontaneous combustion and burning Vladimir Putin

Our columnist takes his life into his own hands by witnessing the ceremonial destruction of Russian premier Vladimir Putin.

Credit: Alamy

Jason Goodwin: 'Our headmaster was more Gilderoy Lockhart than Dr Arnold'

The graduation ceremony of Jason Goodwin's son reminds our columnist of the latin prayers which were so prolific in his

Credit: Alamy

Jason Goodwin: How to turn a majestic but unlucky deer into a freezer-full of meals

Our columnist Jason Goodwin makes the most of a bit of A35 roadkill – with a little help from Christian Dior.

-

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attached

Some of the finest landscapes in the North of England with a 12-bedroom home attachedUpper House in Derbyshire shows why the Kinder landscape was worth fighting for.

By James Fisher

-

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025

The Great Gatsby, pugs and the Mitford sisters: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 16, 2025Wednesday's quiz tests your knowledge on literature, National Parks and weird body parts.

By Rosie Paterson

-

'It may be vain to think that the past was a cleaner, quieter and kinder place, but it felt pretty decent when you knew your GP and your GP knew you, and milk in glass bottles was delivered every morning'

'It may be vain to think that the past was a cleaner, quieter and kinder place, but it felt pretty decent when you knew your GP and your GP knew you, and milk in glass bottles was delivered every morning'Carla Carlisle is homesick for the olden days, when we didn’t know we had it so good.

By Carla Carlisle

-

Patrick Galbraith: We are a brilliant and terrible species who messed it up a long time ago — and that means we have to do things we don't want to

Patrick Galbraith: We are a brilliant and terrible species who messed it up a long time ago — and that means we have to do things we don't want toOur columnist laments the painful decisions on culling wild animals which he argues have to be taken if we're to manage the countryside and maintain biodiversity.

By Patrick Galbraith

-

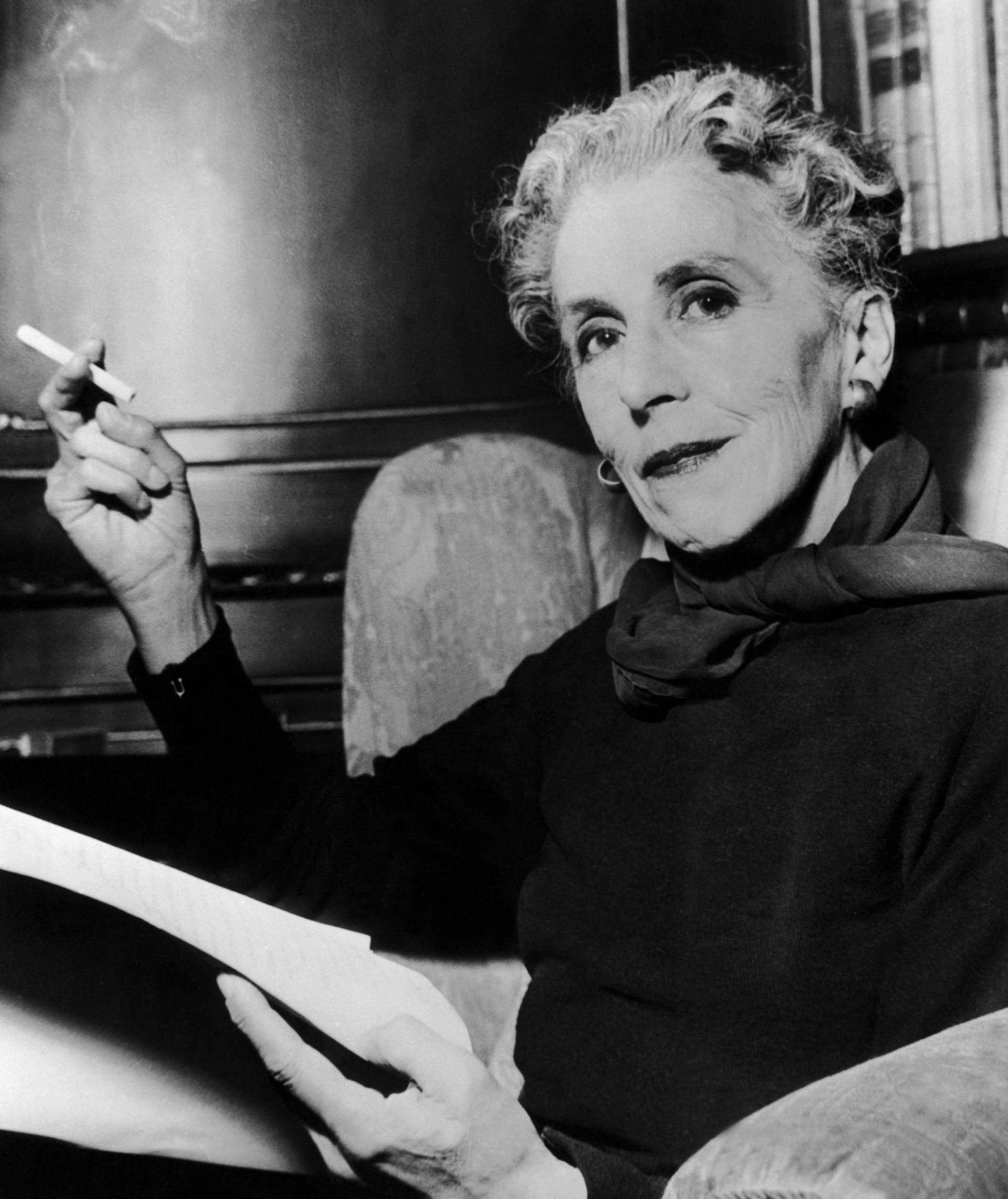

'From the first page until the last, I was in another country, another world... It was like falling in love'

'From the first page until the last, I was in another country, another world... It was like falling in love''There is beauty and there is poverty, order and corruption' — Carla Carlisle on Karen Blixen and Kenya.

By Carla Carlisle

-

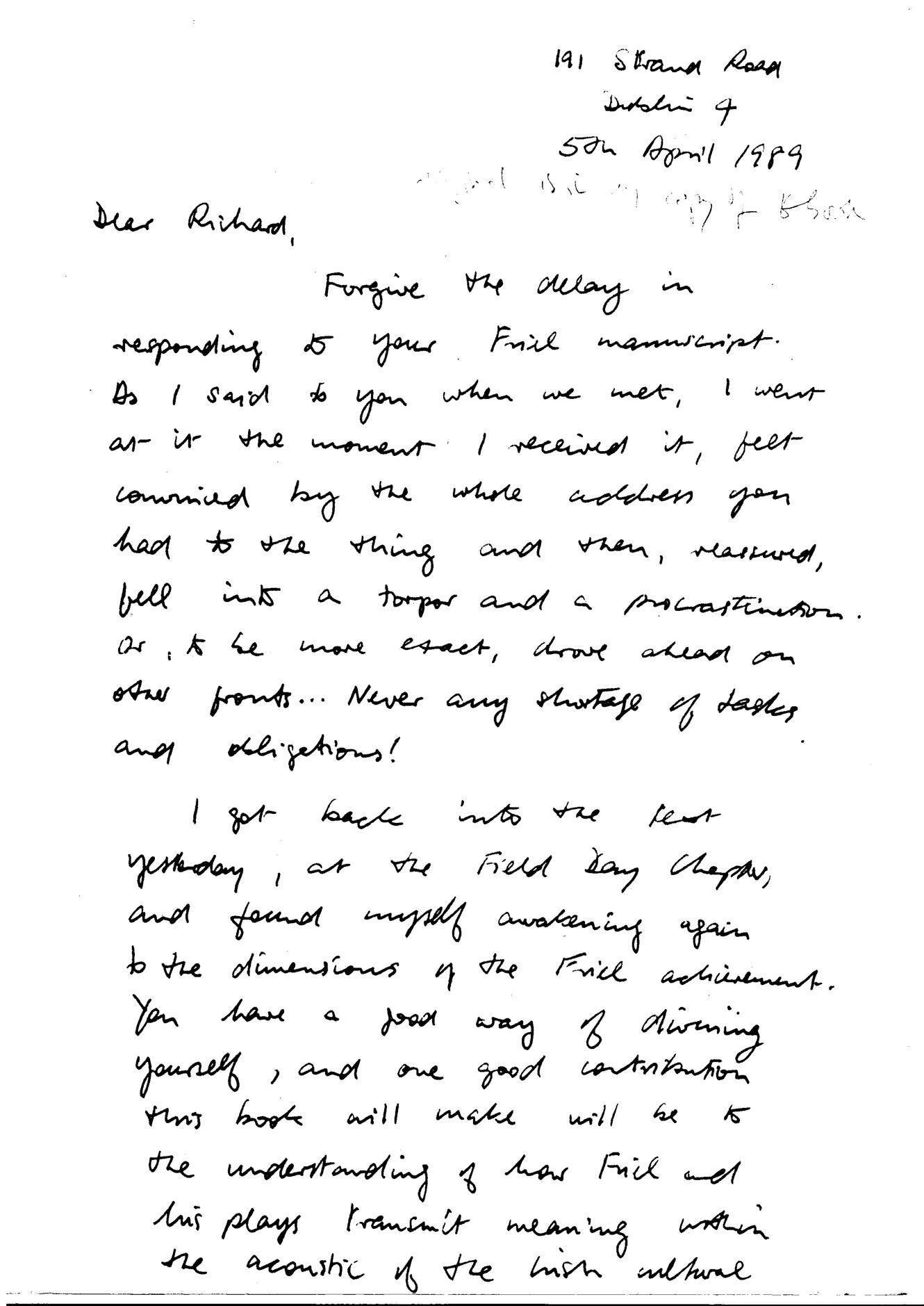

Carla Carlisle: 'Seamus Heaney deserves a sainthood, as well as his Nobel Prize'

Carla Carlisle: 'Seamus Heaney deserves a sainthood, as well as his Nobel Prize'Carla Carlisle applauds The Letters of Seamus Heaney and shares how she couldn't wait until Christmas to devour the collection from the late Irish poet

By Carla Carlisle

-

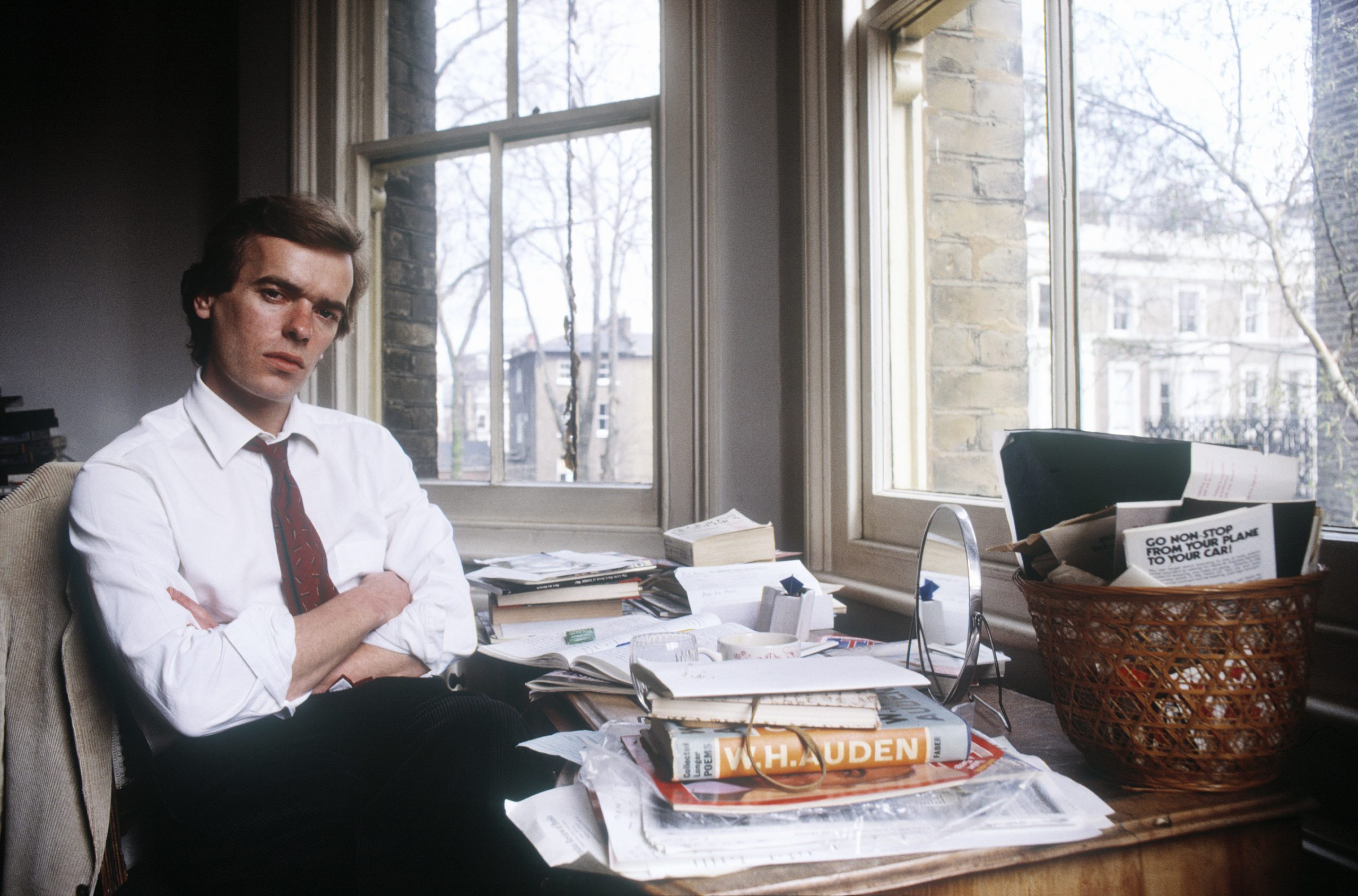

Carla Carlisle on Martin Amis: The 'passionate, graceful, fierce' writer who scared us, challenged us, and brought us understanding

Carla Carlisle on Martin Amis: The 'passionate, graceful, fierce' writer who scared us, challenged us, and brought us understandingCarla Carlisle pays tribute to the late Martin Amis, who died last month.

By Carla Carlisle

-

Carla Carlisle: 'Edit your one and precious life. Prepare for Judgement Day. Do it Now.'

Carla Carlisle: 'Edit your one and precious life. Prepare for Judgement Day. Do it Now.'Carla has been having a bit of a New Year clear-out — albeit one which started last August, and which is NOT going particularly well...

By Carla Carlisle

-

Jason Goodwin's books of the year 2022

Jason Goodwin's books of the year 2022Our columnist Jason Goodwin shares the books that have entertained and enlightened him this year.

By Jason Goodwin

-

'By the time I reached chapter seven I was nauseated by the sheer volume of stuff I owned'

'By the time I reached chapter seven I was nauseated by the sheer volume of stuff I owned'Jonathan Self's chance encounter with a book shifts the way he sees his belongings... but how long will his urge to declutter last?

By Jonathan Self