Jason Goodwin: 'Some empires take centuries to decay... others crumble like a sandcastle assaulted by the tide'

Our columnist laments the apparent beginning of the end of our current empire – but points out that it has ever been thus.

News filters down to us here but slowly and the political excitements of the past week or so reminded me how, five years ago, through a process almost Boot-like in its absurdity, I found myself giving an address to a diplomatic audience at the European Commission headquarters in Tallinn, Estonia.

I approached the rostrum rather like Gussie Fink-Nottle condemned to extemporise before an audience of fifth-form girls and their headmistress. Simultaneous translators crouched at their microphones. Ambassadors nodded their silvered heads.

It was long before the referendum was so much as a twinkle in the Cameronian eye and I took as my theme the Fall of Empires, meaning to address the hubris that surrounds all imperial projects, the wild assurance that theirs will last for 1,000 years.

They never do. They have to say so, however, frequently and loudly, because inspiring awe is an element of empire.

'The British Empire was packed and ready to go in a couple of decades. In only three years, the Soviets collapsed like a sandcastle assaulted by the tide.'

Small democracies don’t go in much for all that majesty and pomp, the military march past, the durbar, the colossal statuary, the triumph. Flinging Christians to the lions is a distinctly imperial gesture. When the Ottomans sent the sultan to the mosque on Friday, they hung all the horses in slings on Thursday night, to ensure that they walked with becoming gravity in procession. That, too, is empire style.

By empire, I mean a congeries of people, speaking different languages and perhaps having different faiths, whose interests and projects are all tethered in a single direction by a caste or emperor. The people can do nothing about it for years, even for centuries: the rewards of empire are cunningly well distributed, the leaders dextrously co-opted, the soldiers paid, the laws maintained.

Eventually, inevitably, something goes wrong. The emperor forgets to share or proves incapable of keeping the peace and, before you know it, the constituent parts of his empire begin to recognise that they could do things better themselves.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

'An empire was no longer justifiable, morally, financially, commercially or militarily'

Some go overnight, like those steppe empires strung together by fast-moving horsemen, which collapse when their Genghis or Attila dies. Some take centuries to decay, such as the Ottomans, whose demise was widely expected in the 17th century, but who saw out the First World War. Others, including Persia and China, seem to bloom and decay and bloom again. The British Empire was packed and ready to go in a couple of decades. In only three years, the Soviets collapsed like a sandcastle assaulted by the tide.

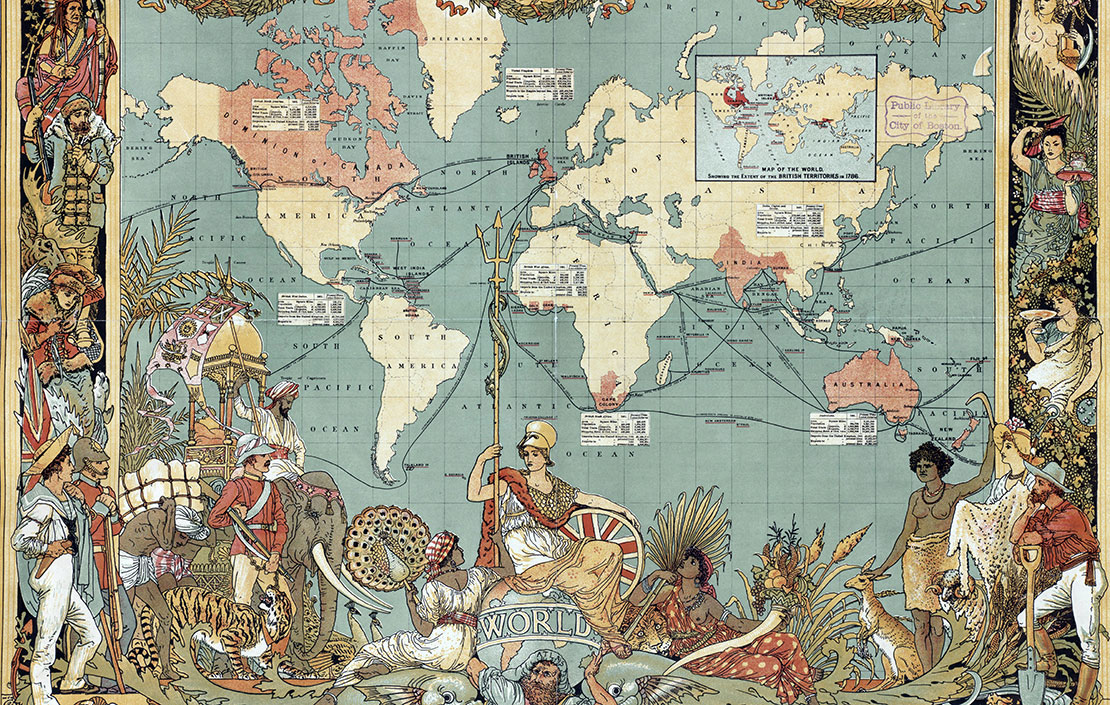

In the case of the British Empire, splashed pink across the Mercator Projection of the world as little as 70 years ago, two unimaginably costly World Wars revealed that the game wasn’t worth the candle. An empire was no longer justifiable, morally, financially, commercially or militarily. The colonies could govern themselves and so Macmillan went through Africa, riding the wind of change, arranging independence with national leaders and taking orders for the O- and A-Level textbooks published by the family firm on the side.

I’m not sure what the Tallinn gathering thought of my remarks. From my notes, I see that I mentioned Atlantis and Ozymandias, quoted a Polish finance minister about the likelihood of war in Europe and observed that the three Baltic republics had emerged three times from the rubble of empires – the Tsarist, the Nazi and the Soviet – in the course of the 20th century. ‘The tumult and the shouting dies;/The Captains and the Kings depart.’

The only certainty, Kipling pointed out in a poem written for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897, is that empires disappear.

Far-called, our navies melt away; On dune and headland sinks the fire: Lo, all our pomp of yesterday Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!

I left that one for the simultaneous translators and bowed out.

Curious Questions: Why do the British drive on the left?

The rest of Europe drives on the right, so why do the British drive on the left? Martin Fone, author

Credit: Jaguar advert

The six reasons why British actors make the best movie bad guys

British actors are simply the best in the world at being bad. Jonathan Self explains why.

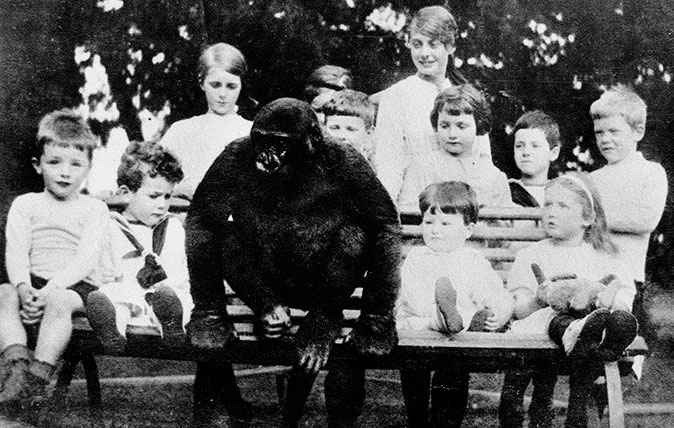

The strange tale of the gorilla who went to an English country school

A baby gorilla sold in a London shop during the First World War lived the life of a young English

-

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producers

380 acres and 90 bedrooms on the £25m private island being sold by one of Britain's top music producersStormzy, Rihanna and the Rolling Stones are just a part of the story at Osea Island, a dot on the map in the seas off Essex.

By Lotte Brundle

-

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The Season

'A delicious chance to step back in time and bask in the best of Britain': An insider's guide to The SeasonHere's how to navigate this summer's top events in style, from those who know best.

By Madeleine Silver