Jason Goodwin: 'In those days, the French government seemed to use sugar wrappers to effect social change'

Jason Goodwin speaks of collections – from stamps and bus tickets to sugar packets and mushrooms.

Every year for the past four years, members of the Artworkers’ Guild in London have assembled a Table Top Museum at the guild’s handsome headquarters in Queen Square. It’s a museum of museums, in fact, because each of the artworkers involved displays a personal collection. It might be passport photos or plastic clothes pegs or the various mincers that Peter Quinell has been ‘collecting unenthusiastically since 1983’. All have their own, sometimes grisly, sometimes joyous, fascination.

You never know what people will collect. I was recently at lunch, the other guest being a large and anxious-looking Italian who barely spoke. I only guessed he was a dealer when, over the coffee, he produced a leather case, with a clasp, containing a marble Roman dildo that, the man assured us, had belonged to the controversial murdered film-maker Passolini. He assumed, correctly, that our host would be interested.

As a child, my stamp collection was made in the shadow of the album that belonged to my Russian godfather, the mushroom-picker, who had escaped St Petersburg in 1921 by leaving everything behind and travelling only in the clothes he stood up in. If I mentioned, say, the Penny Black, he would look thoughtful for a few moments and murmur that, in his St Petersburg collection, he once had three. Two, he might add, were unmounted mint. It was a kind of torture. To me, it seemed inconceivable that he had left Russia with his hat instead of his stamp album.

I collected Continental sugar-cube wrappers, mostly French. On holiday, I would take the sugar that came with my parents’ coffee, eat the cubes inside and then smooth out the wrapper and examine it. In those days, the French government seemed to use sugar wrappers to effect social change, although I was fairly sure that only a handful of people had noticed and even fewer cared.

A series on women chemists, for instance, portraits and dates printed on the wrapper, was sponsored by the Ministry for Gender Equality. There were also more conventional runs depicting wild animals, popular sports or famous writers. It wasn’t wildly interesting, but its existence was a surprise.

'Major activity was required if I found myself close to 9999 because I had to stay on the bus for it and secure the holy of holies.'

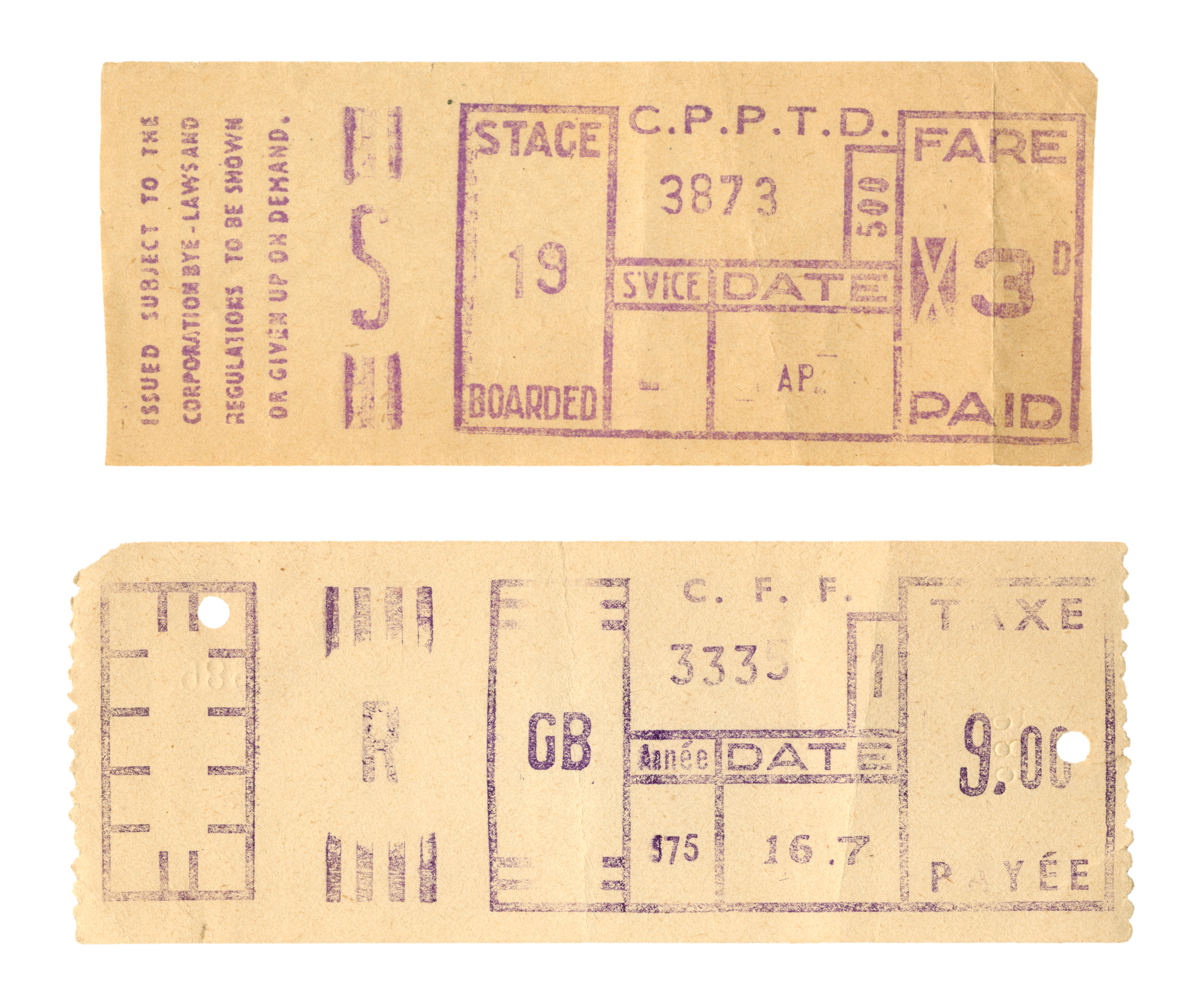

The cream of my collecting mania came from going to school in London by bus. In those days, conductors produced your ticket from a machine slung from a strap. They set the dials and cranked a handle and the machine printed off your ticket in lilac ink on a roll of very pale paper.

There were various codes the conductor set, including the class of ticket, whether ORD for ordinary or C for child, and other categories I’ve forgotten, but what roused the collector in me was the four-figure number printed on the bottom.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

One afternoon, I noticed that my ticket was numbered 1109. It didn’t take a genius to see that here was something worth having. ‘Excuse me,’ I said to the American tourist seated in front of me, ‘could I possibly have your ticket when you leave the bus?’ Sure enough, theirs had the palindromic number 1111. From then on, I was hooked.

I gathered the scales and the arpeggios of bus-ticket numberings: 1234 was a good one, but 4321 was more satisfactory to the cognoscento – me. I knew of no others. Major activity was required if I found myself close to 9999 because I had to stay on the bus for it and then, obviously, secure the holy of holies which followed on, when the machine clocked itself and produced 0000.

Conductors were sometimes irritated and sometimes amused and passengers were usually generous, although I remember one man who refused to part with his treasured ticket after I had explained why I wanted it.

I’m not quite sure what I collect now – mushrooms, perhaps. They are in a league with bus tickets and clothes pegs because you can’t tell where and when the next one will show up. It may be a religious impulse. As the critic Walter Benjamin wrote: ‘Every second of time was the strait gate through which Messiah might enter.'

Jason Goodwin: Keeping up with the Jehovahs

'I don’t get into theological debate with them; I simply like to bask awhile in their radiant happiness'

Perfect pilaf rice made simple: A skill that every cook should learn for life

Writer, historian and chef Jason Goodwin whips up perfect pilaf rice.

Jason Goodwin: ‘The washing-up is being done by a hulking fellow who, moments ago it seems, knelt on a chair at the kitchen table’

Jason Goodwin looks at his nearly-fully-grown children and wonders how it all came to this. (In a good way.)jas

Credit: Alamy

Jason Goodwin: 'Our headmaster was more Gilderoy Lockhart than Dr Arnold'

The graduation ceremony of Jason Goodwin's son reminds our columnist of the latin prayers which were so prolific in his

-

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbinding

'To exist in this world relies on the hands of others': Roger Powell and modern British bookbindingAn exhibition on the legendary bookbinder Roger Powell reveals not only his great skill, but serves to reconnect us with the joy, power and importance of real craftsmanship.

By Hussein Kesvani

-

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary Britain

Spam: The tinned meaty treat that brought a taste of the ‘hot-dog life of Hollywood’ to war-weary BritainCourtesy of our ‘special relationship’ with the US, Spam was a culinary phenomenon, says Mary Greene. So much so that in 1944, London’s Simpson’s, renowned for its roast beef, was offering creamed Spam casserole instead.

By Country Life