Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?

The history of the Olympics is full of curious events which only come to prominence once every four years. Martin Fone takes a look at one of the oddest: race walking, or pedestrianism.

The Olympic Games offer a quadrennial opportunity to shine the spotlight on some sports that would otherwise languish in obscurity. One such is race walking, which made its Olympic debut in 1904. The discipline has three events scheduled for Paris: two races over twenty kilometres, one each for men and women; and one over 50 kilometres for men only.

There are essentially only two rules. The competitor’s back toe cannot leave the ground until the heel of their front foot has touched and the supporting leg must straighten from the point of contact with the ground until the body passes directly over it. Infractions are judged by eye — no VAR here!

A filler in the Olympic TV schedules between the more popular track and field events it might be, but competitive walking, known then as pedestrianism, was one of the first organised competitive sports in Georgian England, along with boxing and horse racing. With no barriers to participation as no specialised equipment was needed, success offered competitors the opportunity of walking away with a substantial purse, far more than they could earn by working.

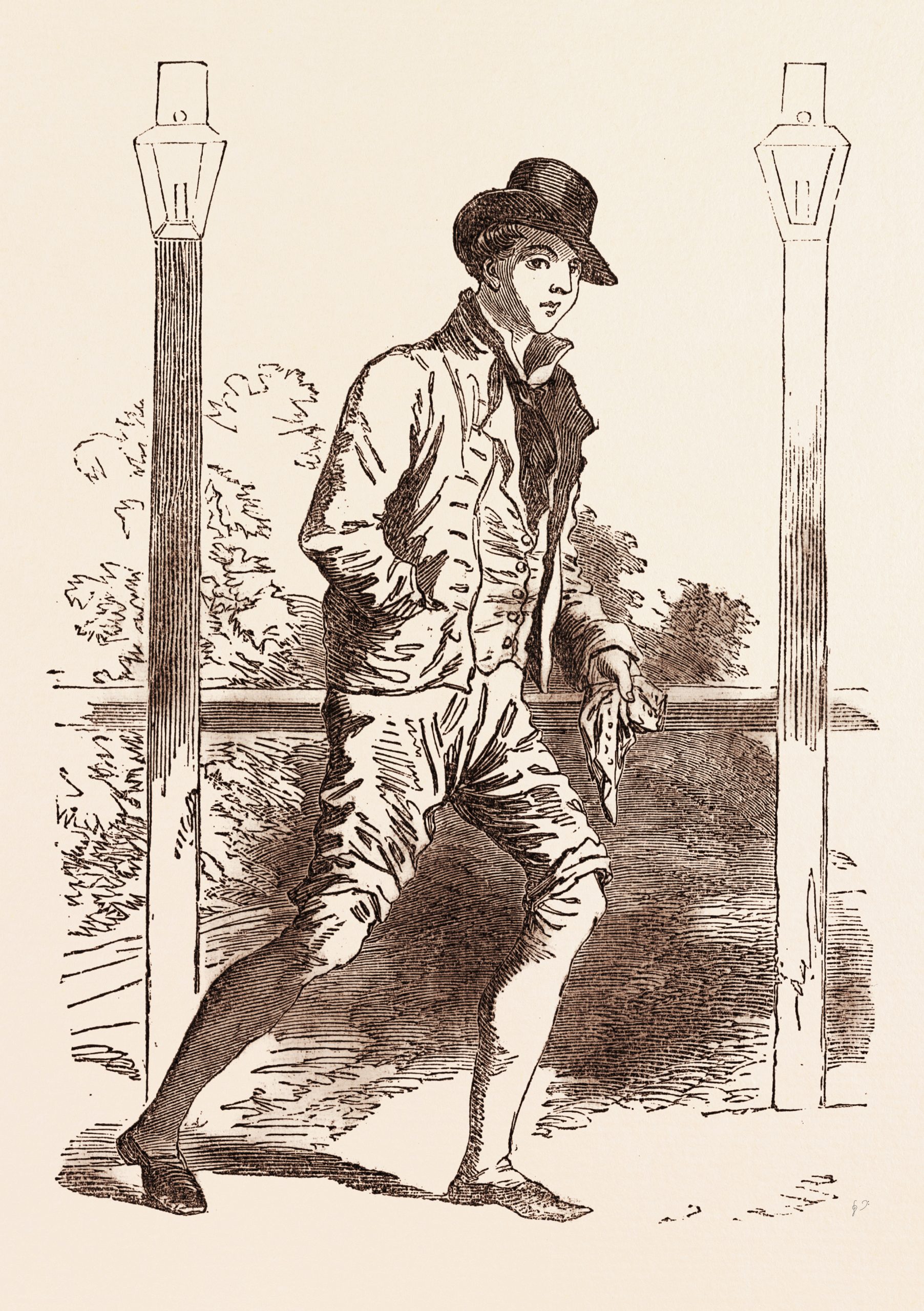

Captain Robert Barclay Allardice, known simply as Captain Barclay, was a leading proponent and an early British sporting hero. Born in Stonehaven in 1779, one of eight children, he was immensely strong, his party piece being to lift from the floor to the dinner table an eighteen-stone man who was standing on the palm of his hand.

Showing early promise as a 15-year-old by winning a 100 guineas wager walking heal to toe for six miles in an hour, he demonstrated his powers of endurance in his first recorded competitive walk, covering 110 miles in 19 hours 27 minutes in a muddy park in 1796. With a reputation for accepting seemingly impossible challenges, he began to prepare for the ultimate pedestrian feat, walking a mile an hour for a thousand hours consecutively.

Others had accepted similar challenges but had fallen short. A tailor made an unsuccessful attempt in 1772, walking a course on ‘a spot of ground marked out for the purpose near Tyburn Turnpike’, while a man called Jones tried to walk a mile an hour for a month but had to retire after three weeks. Lack of sleep, swollen legs, and other medical problems defeated others, but a Gloucestershire man, rather sensibly, had ridden a horse one mile an hour over a thousand hours on Stinchcombe Hill in Dursley, accomplishing the feat ‘with ease’.

Barclay began his attempt just after midnight on June 1, 1809 on a half-mile course laid out on smooth and uncultivated land near Newmarket. For lighting, seven gas lamps were hung on poles 100 yards apart and tents were erected for his assistants who recorded weather conditions and Barclay’s demeanour at each stage.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

His tactics were to start a mile around a quarter of an hour before the end of an hour immediately followed by another mile at the start of the next, thus ensuring around ninety minutes’ rest before starting the next two miles. However, it was a dangerous strategy as occasionally he would oversleep and have to hurry over the course to ensure completion of a mile within the hour.

Barclay completed his extraordinary feat of endurance on July 12th, having walked for 12 days and 8 hours over the course of 41.7 days, losing 32 pounds in weight in the process. Picking up a purse of 16,000 guineas, he celebrated by taking a warm bath.

Eschewing any form of rigorous training, reputedly being a hearty eater and drinker, and preferring a top hat, cravat, warm woollen suit, lamb’s wool socks and thick-soled shoes to any athletic strip, Barclay’s success, according to Walter Thom in his book Pedestrianism (1813), was down solely to his strength and unique walking style. He would bend his body forward to throw his weight on his knees, taking short steps and raising his feet only a few inches from the ground.

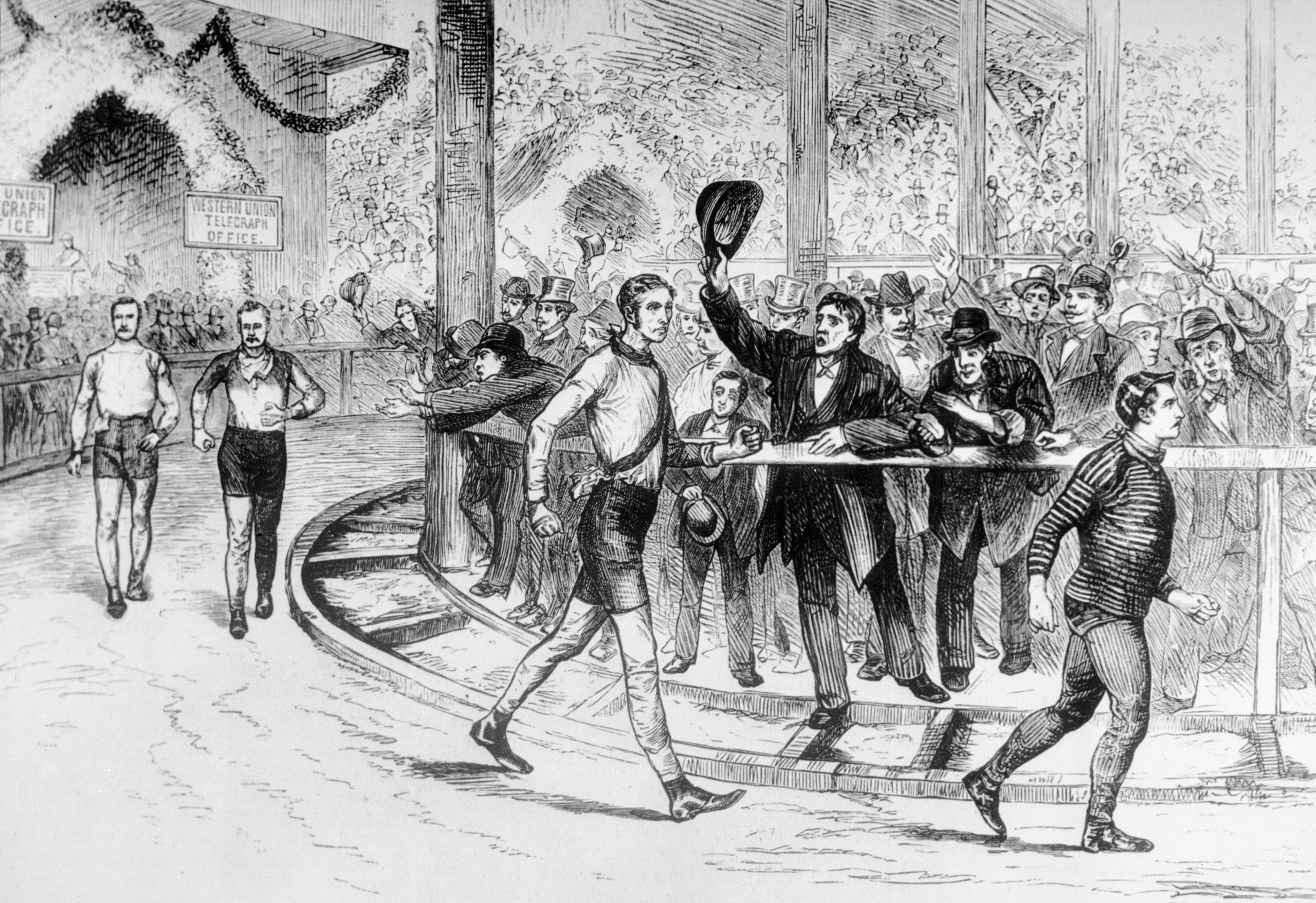

Over 10,000 spectators had watched Barclay’s feat and some 100,000 guineas wagered on the outcome. Pedestrianism had become a popular spectator sport in an age when everybody walked, requiring little recherché knowledge to appreciate the style and stamina of a good walker, while offering the crowd an opportunity to indulge in its favourite pastimes, drinking and gambling.

This could produce a heady cocktail as George Wilson, known as the Blackheath pedestrian although he was born in Newcastle upon Tyne, discovered to his cost. On September 11, 1815, at the age of 50, he set out to walk fifty miles over a twelve hour period each day for twenty days around a mile long triangular course near the Hare and Billet public house at Blackheath, drawing large crowds to watch his progress. They kicked up so much dust that Wilson’s breathing began to suffer, prompting some of his supporters to print handbills urging the crowd to give him room.

Those who had bet against Wilson resorted to increasingly desperate measures to thwart him. At one point he was handed a glass of tainted water that upset his stomach and later a couple stepped out of the crowd, assaulted him and when he fought back, threatened to have him arrested.

For the Hare and Billet’s landlord Wilson’s exploits proved a goldmine, with 1,296 quarts of beer sold in a day. A Tartar fair was set up to entertain the crowd, there were circus acts including a trapeze artist, and an elephant sat in front of the pub. So crowded were the streets that vehicles ‘pressed forward with an unwise impatience amidst the general crush. Friend and foes seem to have forgotten all the usual courtesies of good manners’.

The authorities were forced to take action, banning alcohol outside the pub and clearing the booths away. On the 16th day of Wilson’s attempt, a warrant was issued for his arrest for disturbing the peace with a ‘very tumultuous assemblage of people from the surrounding and other parishes and occasioning a considerable interruption to the peace of the inhabitants’.

Under virtual house arrest until the hearing and after walking just over 750 miles, Wilson had to abandon his attempt, although a public subscription raised his 100 guinea purse. The case was eventually dismissed on a technicality and he was ‘discharged and conducted home in triumph, decorated with ribbons, and accompanied by shouts of the multitude’.

Throughout the first half of the 19th century other publicans sought to emulate the enterprising landlord of the Hare and Billet by organising pedestrian matches, putting up the competitors, taking care of the publicity and running a book, certain in the knowledge that they would make a tidy profit.

Reviewing the growth of pedestrianism since 1760, Walter Thom attributed its fashionable status to the ‘patronage of men of fortune and rank’, while the Bristol Gazette in 1815 commented on the number of gentlemen infected by ‘the rage for walking’. Others adopted a more censorious tone, a correspondent to the Cambrian fulminating that ‘a whole race of fifty miles a day men had arisen, and what…before was the disease of an individual is now become an epidemic’ while the Morning Post called it a ‘pedestrian mania’.

It was not to last, though, as Victorian distaste for gambling and the consequences of excessive alcohol consumption, at least in public and amongst the masses, together with the suspicion that there was widespread cheating as competitors tried more outlandish feats of endurance saw pedestrianism fall out of favour. By the end of the 19th century football rather than pedestrianism had become the opium of the masses.

If you catch race walking on the television, give a thought to Captain Barclay.

Credit: AFP via Getty Images

Curious questions: Did the modern Olympics really start in Much Wenlock?

Martin Fone traces the history of the Olympics and examines the contribution of Shropshire doctor William Penny Brookes.

Curious Questions: What was the first ever televised sporting event?

Over 20 million people have been tuning in to watch England's stirring exploits at Euro 2020, and the huge numbers

Credit: Morgan Hancock / Getty

Curious Questions: Why do cricketers call it a 'duck' when they get bowled out for 0?

Martin Fone, author of 50 Curious Questions, explains how a duck egg led to the popularisation of a term in

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa Harrison

How an app can make you fall in love with nature, with Melissa HarrisonThe novelist, children's author and nature writer Melissa Harrison joins the podcast to talk about her love of the natural world and her new app, Encounter.

By James Fisher

-

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera season

'There is nothing like it on this side of Arcadia': Hampshire's Grange Festival is making radical changes ahead of the 2025 country-house opera seasonBy Annunciata Elwes

-

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?Martin Fone takes a look at the history of London's coalgates, and finds that the idea of taxing things as they enter the City of London is centuries old.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?Final words can be poignant, tragic, ironic, loving and, sometimes, hilarious. Annunciata Elwes examines this most bizarre form of public speaking.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?Tales of swashbuckling pirates have entertained audiences for years, inspired by real-life British men and women, says Jack Watkins.

By Jack Watkins

-

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylight

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylightMartin Fone tells a tale of sunshine and tax — and where there is tax, there is tax avoidance... which in this case changed the face of Britain's growing cities.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?A completely fair game of chance, or an opportunity for those with an edge in human psychology to gain an advantage? Martin Fone looks at the enduringly simple game of rock, paper, scissors.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?In days gone by, left-handed children were made to write with the ‘correct’ hand — but these days we understand that being left-handed is no barrier to greatness. In fact, there are endless examples of history's greatest musicians, artists and statesmen being left-handed. So much so that you'll start to wonder if it's actually an advantage.

By Toby Keel

-

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?The tax-year calendar is not as arbitrary as it seems, with a history that dates back to the ancient Roman and is connected to major calendar reforms across Europe.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Why does Easter move dates every year?

Curious Questions: Why does Easter move dates every year?Phoebe Bath researches why exactly Easter is a called a 'moveable feast'.

By Country Life