Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?

Tales of swashbuckling pirates have entertained audiences for years, inspired by real-life British men and women, says Jack Watkins.

Blackbeard (real name, Edward Teach), Black Bart (Bartholomew Roberts), Capt William Kidd and Anne Bonny sit in a rogues’ gallery of British pirates that still intrigues us today. As Brenda Ralph Lewis writes in The History of Pirates: ‘Pirates and privateers… are among the few people in history to retain their fascination long after their own lifetime.’

Of course, piracy isn’t confined to the ‘Golden Age’ of the late 17th and early 18th century; it has been going on ever since cargo-carrying vessels set sail. The best-known accounts are associated with more far-flung locations in later centuries, such as the Barbary Coast and the Spanish Main, but the English Channel was a piracy hotspot in Roman and medieval times. The Roman Carausius, a future emperor, was employed by the Senate to patrol it in the 3rd century AD. He hunted for Saxon and Frankish buccaneers, helping himself to a share of the spoils on apprehending them.

In the Middle Ages, ships hugging the coastline were an easy target for opportunists able to launch lightning attacks, often operating under a cloak of respectability because ship owners were useful at a time when the Crown had limited naval resources. For John Hawley, being licensed by the King during the Hundred Years War with France to patrol the Channel and attack enemy ships was a profitable business, although complaints of piracy were made against him by neutral shipping merchants. Eventually, he fell from favour and had a spell incarcerated in the Tower of London, yet he was able to accumulate estates in Devon and Cornwall and was Mayor of Dartmouth 14 times between 1374 and 1401.

Hawley’s practices illustrate the fine line between being a privateer, sanctioned by a monarch in times of war to attack hostile vessels, and a pirate, operating without official authorisation. By the 16th and 17th centuries, Spanish conquests in the New World led to more opportunities for pirates to attack galleys carrying silver, gold and jewels back to Europe. This was the era of Elizabeth I’s ‘sea dogs’, notably Sir Francis Drake, Sir Martin Frobisher, Sir John Hawkins and Sir Walter Raleigh. Their privately funded voyages to raid Spanish ships and territories were profitable to them and the Crown, but Elizabeth was forced on occasion to express official regret over their exploits, although secretly delighting in the damage they did to her enemy.

By the mid 17th century, the Caribbean seas were riddled with pirate ships. The Spanish Main had seen the Spanish and Portuguese joined by their English, French and Dutch rivals in establishing colonies and outposts. It was into this melting pot that the Welsh-born Henry Morgan seems to have arrived in 1654 with an expedition sent by Cromwell, who was keen to create a Protestant empire in the Americas.

In Jamaica, the corrupt British governor Thomas Modyford used buccaneers to attack Spanish vessels, enriching himself in the process, and Morgan proved an able commander. He stepped out of line by attacking Panama in 1671, just after the Treaty of Madrid had been signed, but, when summoned back to London, his plea of ignorance of the treaty was accepted and he returned to Jamaica as Lt-Governor. However, his star fell once again, before his death in 1688, with the 1684 publication of an English translation of Alexandre Exquemelin’s The Buccaneers of America, which described him as a cruel and lustful character.

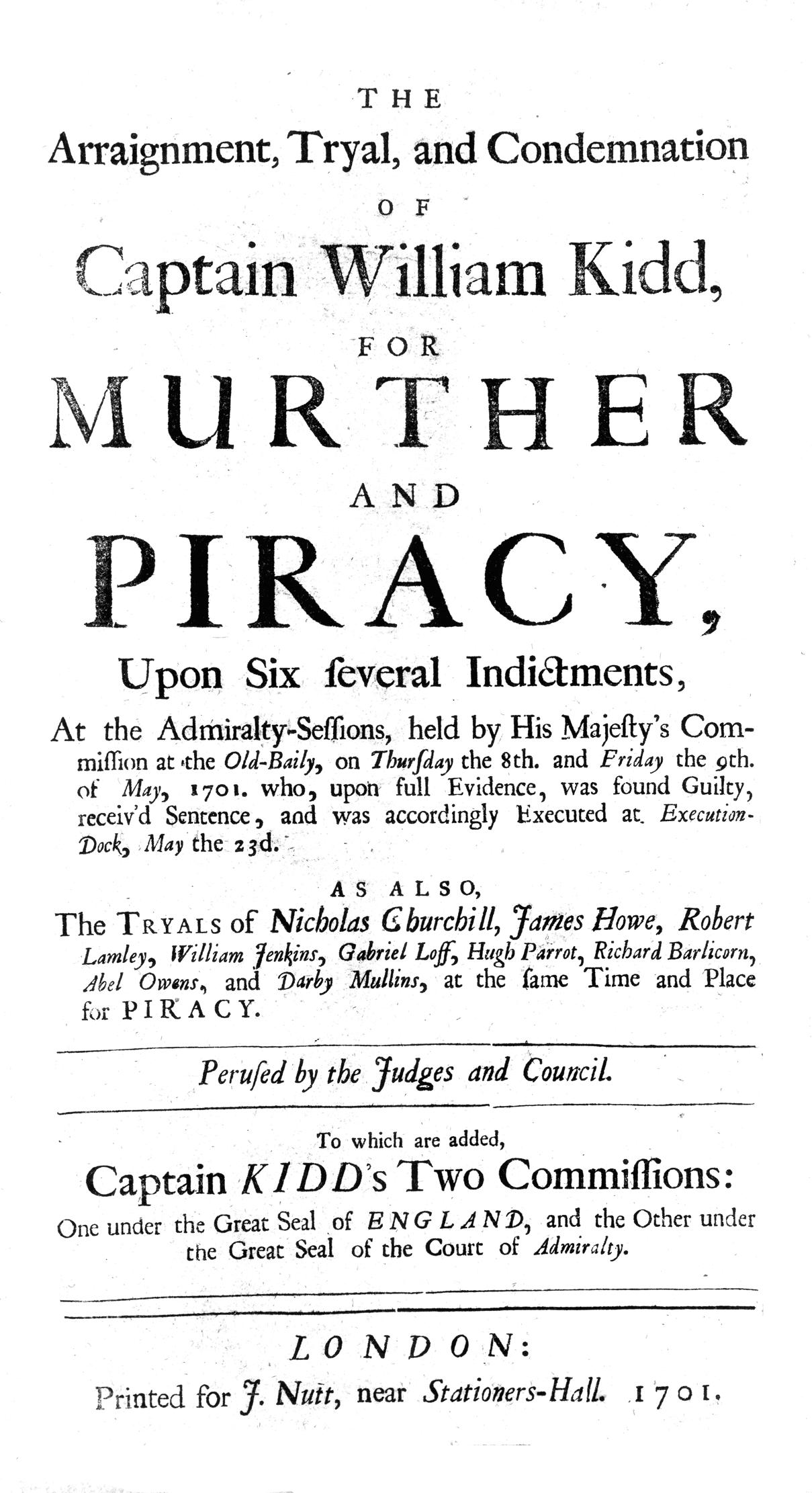

Forever associated with buried treasure on mysterious islands, the pirate Kidd had apparently respectable beginnings. The son of a Presbyterian minister, he began well as a privateer, launching a successful raid on a French colony off the coast of North America in the 1690s, then settled in New York, married and became a regular churchgoer. However, his thirst for the sea drew him to take command of a pirate-hunting ship, Adventure Galley. Soon afterwards, a warrant was put out for his arrest. By the time he returned, in chains, to England, he had stolen an estimated £26,000 (some £8 million today) worth of goods. Kidd was executed in 1701 and his tarred body left gibbetted in an iron cage at Tilbury Point.

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The career of Teach was much shorter. A privateer during the Spanish War of Succession (1701–14), he then turned to piracy in the Bahamas. He was described in Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Pyrates (1724) as ‘a tall, spare man with a black beard which he wore very long’, hence Blackbeard. His appearance was made more terrifying by the slow-burning fuses that hung from his hat when entering battle. He maintained tenuous control of his crew by fuelling them with rum and once tried to smoke them out of the ship’s hold with brimstone — in an attempt to simulate the Devil’s behaviour. Blackbeard preyed on ships in the Caribbean in a sloop he had seized and renamed Queen Anne’s Revenge. His luck ran out in November 1718, when he was felled by at least five pistol shots and countless cutlass slashes in a skirmish with the Royal Navy. His killers sailed off with his severed head hanging from the bowsprit.

Far more disciplined than Blackbeard was Roberts, or Black Bart, who had started out in the slave trade before turning to piracy on the Guinea coast in 1719. Drinking was banned after lights out aboard his ships, but he still traded on a grisly reputation, flying under a flag depicting himself standing on two human skulls. Before he was killed by a pistol shot in a stand-off with an English man-o-war in 1722, he had taken the spoils of 400 ships.

Among the few female pirates were Bonny and Mary Read. Johnson’s history claims that both were illegitimate and dressed as boys from childhood. Read first enlisted in the Army, before falling in with a company of pirates led by the flamboyantly attired John Rackham, or ‘Calico Jack’. It was among the rabble that she met Bonny — who had also opted for the cutthroat life, having beaten up a would-be rapist. The pair outshone their male counterparts for bravery and toughness, being the only crew members to hold their nerve when Rackham’s ship was boarded by pirate hunters in 1720. Both escaped hanging by pleading pregnancy and it was said Bonny lived on to the ripe old age of 84. Rackham was not so fortunate. Bonny visited her former lover as he awaited the gallows and told him that she was ‘sorry to see him in such a situation, but if he’d fought like a man, he need not have been hang’d like a dog’.

By the early 1720s, the glory days of pirating were numbered. Imperial powers no longer felt it in their trading interests to have merchant ships assailed by buccaneers on the high seas. As a result, most pirates were hunted down and executed. Yet the curious fascination that society had, and still has, for pirates never faded. Blackbeard; or the Pirate’s Princess, by James Cross, was a musical drama of the 1800s, first staged in 1798; The Pirates of Penzance, a later send-up of pirate melodramas by Gilbert and Sullivan, was wildly popular with 19th-century audiences.

As the ‘shiver me timbers’ image was duly sanitised, pirates became suitable material for children’s adventures, such as Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island and J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. One of Hollywood’s great hellraisers, Errol Flynn, was suitably swashbuckling as a pirate in Captain Blood (1935) and as an Elizabethan privateer in The Sea Hawk (1940).

In the 21st century, the appetite for cutthroat entertainment, served up with tongue firmly in cheek, is reflected in the box-office returns for the ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’ films, starring Johnny Depp as Captain Jack Sparrow. More visceral fare is television’s Black Sails, the thrilling tale of how Long John Silver of Treasure Island came to be. Buckle up, me hearties.

Jack Watkins has written on conservation and Nature for The Independent, The Guardian and The Daily Telegraph. He also writes about lost London, history, ghosts — and on early rock 'n' roll, soul and the neglected art of crooning for various music magazines