Curious Questions: Why did the Garden Cities of Tomorrow never catch on?

The worst excesses of the Industrial Revolution prompted some truly forward-thinking urban planning as far back as the 19th century — yet today, precious few of us live in the idyllic 'garden cities' that were dreamed of. Martin Fone looks at what happened, the benefits that came to pass from those fresh ideas, and what got lost on the way.

Town and country need not necessarily be poles apart, but in Britain the Industrial Revolution sparked a massive redistribution of population. While some 80% of the population had lived in the countryside in the early 18th century, by the last decade of the nineteenth century over three quarters were living in town and cities. The lure of finding more lucrative employment and streets paved with gold had turned into a squalid nightmare of an overcrowded, insanitary, hand-to-mouth existence, what Frederic Osborn called the ‘urban disease’.

Some enlightened thinkers began to consider how these dreadful urban conditions might be improved. One such was parliamentary stenographer, Ebenezer Howard, whose vision was to combine the best of the town and countryside and eliminate the disadvantages of both. ‘Human society and the beauty of nature’, he wrote in Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform (1898), ‘are meant to be enjoyed together…Town and Country must be married, and out of this joyous union will spring a new hope, a new life, a new civilisation’.

Howard’s vision was a town where land was owned communally with mixed-tenure houses that were genuinely affordable, and where there was a wide range of local jobs within easy commuting distance of the residents’ homes. Houses would be well-designed with gardens, flanked by tree-lined roads and with wide open green spaces nearby. There would be a maximum of 32,000 residents in a town that was self-sufficient, with its own shopping, recreational, and cultural facilities and access to an integrated transport system.

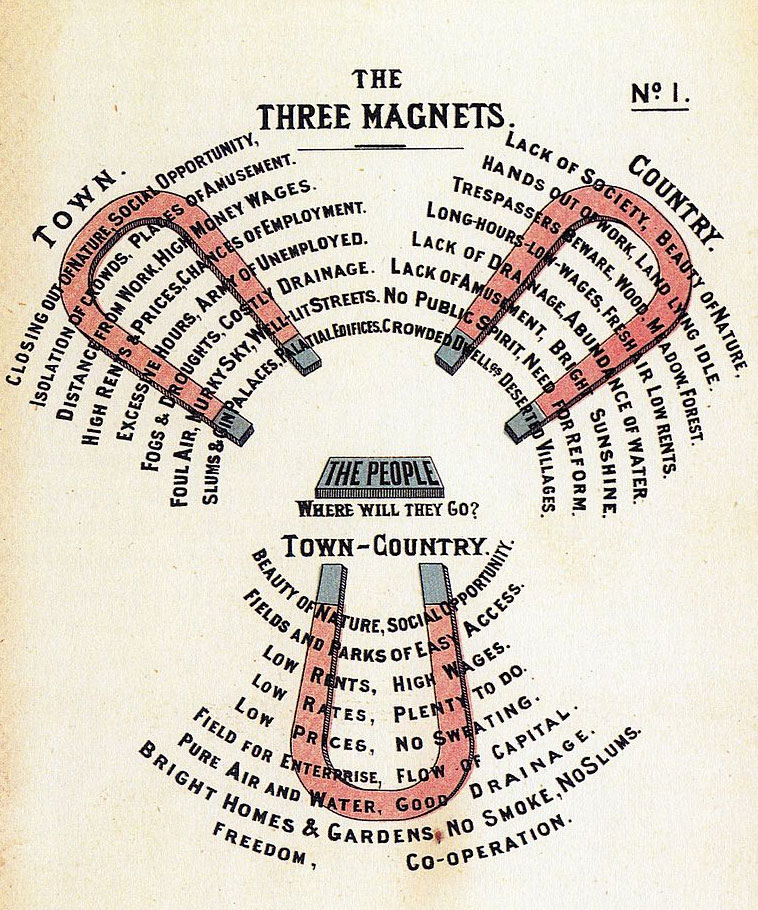

Remembering the strictures of the Liberal Unionist MP, William Sproston Caine — that ‘one good picture is worth many pages of description’ (1891) — Howard set about illustrating his radical concepts of urban design in a diagram, which appeared as a frontispiece to his Garden Cities of To-morrow (1902). It consisted of three magnets, the first of which listed his perception of the pros and cons of living in the town. The second repeated the exercise but from the perspective of living in the countryside. The third, placed towards the bottom of the page, encapsulated the benefits to be obtained by combining the best of urban and country living.

At the centre of the diagram were ‘The People’ and the question ‘where will they go?’ was posed.

Careful scrutiny of Howard’s diagram made its message clear; the poles of the magnet representing the combined benefits of town and country were placed slightly nearer to centre than those of the other two magnets, suggesting that it held a stronger attraction to those who had a choice in the matter. By modern graphical design standards it was overly busy with text written over each magnet and slightly confusing but, at the time, it was a powerful statement of Howard’s beliefs.

Not content with lofty aspirations and mouthing pious platitudes, Howard sought to put his vision into practice, forming, in 1899, the Garden City Association with a mission to promote social justice, economic efficiency, beautification, and health and well-being in an urban setting. He received support moral, political, and, most importantly as he was a man of limited means, financial support from ‘gentlemen of responsible position and undoubted probity and honour’.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

The involvement of these gentlemen was to prove a double-edged sword. While they provided sufficient funds to enable Howard to form a company, First Garden City Limited, and finance the purchase of land in Letchworth and the neighbouring parishes of Willian and Norton, there was a limit to their philanthropy. As shareholders, they anticipated that they would collect interest on their investment if the garden city made profits through rental income. Inevitably, this expectation led to tensions and Howard had to compromise on some of his principles, jettisoning the idea of co-operative ownership without landlords and the freezing of rents at low levels. He was even forced to employ architects who did not share his rigid design concepts.

Nevertheless, with architects Barry Parker and Raymond Unwin at the helm, construction of the world’s first garden city began in 1903. Unwin’s template for housing was that they should be ‘simple and straightforward buildings’ made from ‘good and harmonious materials’. Mirroring Howard’s vision, there were just twelve houses per acre, standing in tree-lined roads and with access to generous open spaces, amongst which were Norton Common and Howard Park.

Along Letchworth Lane they built a row of semi-detached houses complete with picturesque rows of dormer windows and tall chimneys, in one of which, ‘Crabby Corner’ later renamed ‘Arunside’, Parker lived from 1906 to 1935, no finer sign of commitment. To showcase their innovations, they held a number of exhibitions in Letchworth, including the Cheap Cottage and Urban Cottages exhibitions of 1905 and 1907 respectively.

Taking the first industrial estate at Manchester’s Trafford Park as their template, Unwin and Parker built factory units which, for their time, were bright and airy. Typical of their approach was the Spirella factory on Bridge Road with its two glazed workshop wings. There was even room for Britain’s first roundabout, at Sollershott Circus built in 1909.

Parker and Unwin’s manifestation of Howard’s vision won plaudits around the world, and inspired the Hampstead Garden Suburb in 1907. The brainchild of Henrietta Barnett, and laid out by Unwin and Edward Lutyens, showcasing the best of the early twentieth century English domestic architecture, it was described by Sir Nikolaus Pevsner as ‘the most nearly perfect example of that English invention and speciality, ‘the garden suburb’’.

Lured by low rents, tax breaks, and open spaces, the population of Letchworth grew, allowing First Garden City to begin paying out dividends to its shareholders for the first time after a decade of trading. The for-profit approach, though, saw house prices rise to a level unaffordable to the very blue-collar workers whom Howard had most in mind.

While other examples of garden cities were designed around the world over time, the garden city movement stalled in Britain. After pledging to build homes ‘fit for heroes’ after the First World War, the British government focused on adding suburbs on to existing towns and cities rather than creating the hundred new towns that the New Town Movement, of which Howard was a prominent member, lobbied for, let alone any garden cities. New towns, twenty-seven in all, were not built until after the Second World War, and the only other garden city was built as a result of Howard’s do-it-yourself spirit.

Frustrated, he undertook another round of fund raising in 1919 to establish The Welwyn Garden City Corporation and buy land at auction around the Hertfordshire village. Construction began on the new venture in 1920, but its proximity to London, only twenty miles away, meant that it was never as self-sufficient as Letchworth.

Howard’s legacy is best summed up by the American sociologist, Lewis Mumford, who, in 1946, opined that ‘at the beginning of the twentieth century, two great new inventions took form before our eyes: the aeroplane and the Garden City, both harbingers of a new age: the first gave man wings and the second promised him a better dwelling-place when he came down to earth’. We might not have realised Howard's dream, but his three magnets immeasurably improved urban life.

The tale of Knebworth: How does your garden village grow?

A garden city planned by Sir Edwin Lutyens was never brought to completion. Plans to redevelop it today, however, threaten

How the Surrey Hills has inspired generations of writers, artists and visionaries

With its magnificent views, lovely churches and grand country houses, this Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty has proven an inspiration

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

What should 1.5 million new homes look like?

What should 1.5 million new homes look like?The King's recent visit to Nansledan with the Prime Minister gives us a clue as to Labour's plans, but what are the benefits of traditional architecture? And can they solve a housing crisis?

By Lucy Denton

-

Having a ruff day: Kennel Club exhibition highlights the plight of vulnerable spaniel breeds

Having a ruff day: Kennel Club exhibition highlights the plight of vulnerable spaniel breedsPhotographer Melody Fisher has been travelling the UK taking photographs of ‘vulnerable’ spaniel breeds.

By Annunciata Elwes