Curious Questions: Why are four-leaf clovers lucky?

Ian Morton investigates the myths and legends linked to Ireland's favourite plant.

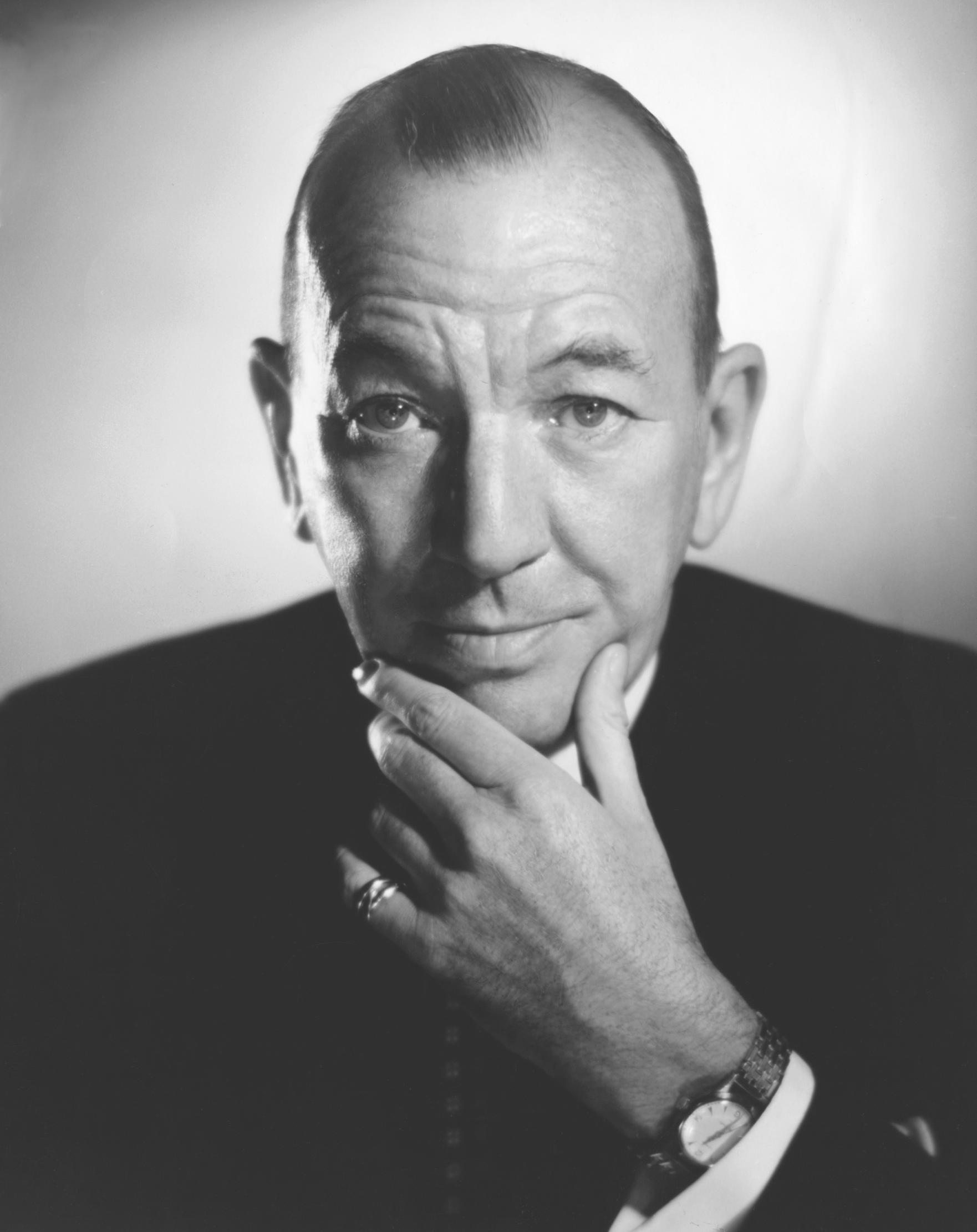

Firstly, we have the Irish question. No, not that one, this one: what is shamrock and what is clover? The sentimental claim of the Emerald Isle to the exclusivity of shamrock was never better expressed than in the 1914 song A Little Bit of Heaven by American songwriter J. Keirn Brennan, which features the lines: So they sprinkled it with stardust, Just to make the shamrocks grow,’Tis the only place you’ll find them, No matter where you go.

Pure blarney. Shamrock and clover are botanically the same and there are 245 recognised species worldwide. To my mind, if there’s a collective noun for clover, it’s a complexity.

Shamrock derives from seamair, from the old Irish semar — meaning clover — and og, meaning small or young. The first published reference to it in English can be found in John Gerard’s Herball of 1597, which noted that ‘meadow trefoils are called Shamrockes’.

Yet who would wish to deny the Irish their national plant? For legend has it that St Patrick — the 5th-century Romano-British missionary that weaned the land away from Celtic polytheism — used clover’s three-leaf configuration to illustrate the Christian trinity, of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost.

Usefully, the number three was already significant in the pagan orthodoxy and in the triumvirate of senior Greek and Roman goddesses. Equally as potent, if not more so, was the number four — the seasons, the ancient elements and the points of the compass — with a rare four-leaf clover proclaiming good fortune, as well as playing a part in druid rituals.

For early Christians, it represented the holy cross and allowed the perception of evil. They believed Eve carried a four-leafed clover with her when she was thrown out of Eden to remind her of paradise lost.

In medieval times, a single woman who put one in her shoe would marry the first wealthy and eligible man she met. The same charm pinned over her door would ensnare the first unmarried man to pass through.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

Strewn in the path of a rural bride, clover gave her protection and the promise of a successful marriage. It provided fodder and silage, enriched poor soil and banished snakes. Fields of clover were believed to attract fairies and wearing a four-leafed clover was said to render them visible. An ointment made from a four-leafed clover or an amulet containing the lucky leaf, together with seven grains of wheat, gave second sight.

A rhyme declared one leaf for fame, one for wealth, one for a faithful love and one for glorious health. A maiden finding a two-leafed stem held the promise of a lover and a four-leafed helped a chap avoid military service, protected against madness, enhanced his psychic powers and promised wealth.

Two people chewing a four-leafed clover together were bound to fall in love and anyone finding a five-leafed one was assured of exceptional powers and great fortune.

Some species found abroad generate large numbers of leaves on one stem. Guinness World Records credits Japanese enthusiast Shigeo Obara of Hanamaki City with 56 — a sure candidate to win the Takarakuji lottery, perhaps.

Those of us content to find only one lucky four-leaf clover may be nonplussed by another Guinness record, registered by 10-year-old Katie Borka of Spotsylvania, Virginia, who found 166 in the space of one hour; a likely US Powerball winner, perhaps.

Our native white clover, Trifolium repens, and red clover, Trifolium pratense, widely planted in British fields and carried to other continents by colonisation, are but two in the global list of members of the Fabaceae or pea family. Here, we may also see the so-called Swedish clover (T. hybridum), which has naturalised since arriving in the early 19th century, the straggling meadow or zigzag clover with rose-purple bloom (T. medium), the hairy and feathery hare’s-foot (T. arvense), the strawberry clover (T. fragiferum), the hop clover (T. campestre) and the very similar T. dubium, which likes dry soil and may be found on roadsides. Few folk perceive them.

Elsewhere in the world, other clover species have garnered a variety of colloquial and rather bewildering names, such as foothill, forest, subterranean, tomcat, cow, buffalo, bull, knotted, notchleaf, bearded, cup, clammy, fewflower, sulphur, whitetip, woollyhead and thimble. Others are known by their location — Persian, Egyptian, Hungarian, Chilean and Santa Cruz.

English folk names included honeystalker or honeysuckle, from the old practice by rural children of sucking the flowers to taste the nectar produced within their 30 to 60 florets.

Preferred by bees and especially bumblebees, white clover deterred witches and, when rubbed on weapons before battle, was thought to render them infallible. It also carried considerable folk value in Wales, where it warded off evil spirits, deflected madness when gathered in a gloved hand and epitomised beauty — in Arthurian legend, Princess Olwen left a trail of white clover wherever she went.

Red clover is one of the world’s oldest crops — the Greeks and Romans fed it to cattle and warhorses. It had great medicinal value, too. Pliny recommended it for poisonous bites and the ancient Chinese prescription for whooping cough survived into medieval Europe and crossed the Atlantic with Dutch settlers.

Traditionally, it served as a diuretic, expectorant, blood purifier, antibiotic, appetite suppressant, relaxant and a treatment for cancer, heart and lung problems. Infused in warm water, it was an aphrodisiac.

Freckles were banished from a face washed with red clover in dawn dew and, added to bath water, it aided financial decisions. Few such nostrums are credible, but modern analysis has identified vitamins B and C, plus phytoestrogens, judged to be relevant in treating menopausal and prostate problems.

Clover miscellanea

• Of indeterminate origin and popular with rugby clubs and the licentious soldiery of two world wars, the bawdy song relating to a romp Roll Me Over in the Clover couldn’t offer greater contrast to Brennan’s ballad and the dozen or so other sentimental songs involving the plant

• The clover-leaf symbol used for the clubs suit in English-language playing cards originates from the French trèfle (clover), adopted in 1480. In Italian, the suit is fiori (flower) and in German/ Swiss Eichel (acorn)

• Celtic football club, predominantly Catholic and Irish in its ethnicity, proudly claims the clover leaf as its symbol (left). Alfa Romeo sports the four-leaf quadrifoglio as a model and brand badge. Sundry businesses large and small endeavour to associate themselves with good fortune with clover-leaf logos • HMS Clover, a Flower-class corvette built in Paisley and launched in 1941, was adopted by Bishop’s Stortford, Hertfordshire. She served as an escort with convoys in South and West Atlantic waters before helping to shepherd the small boats across the Channel for the Normandy invasion. Sold for mercantile duties in 1946 and renamed Cloverlock, she was later purchased by the Chinese navy and became a warship again, leaving service in the early 1970s

Curious Questions: What caused Tulipmania?

Curious Questions: Which bird's song is loudest?

We tend to think of bird song as endearing and delicate — but there are birds out there who would put

Carla must be the only Italian that finds the English weather more congenial than her native country’s sunshine. An antique herself, she became Country Life’s Arts & Antiques editor in 2023 having previously covered, as a freelance journalist, heritage, conservation, history and property stories, for which she won a couple of awards. Her musical taste has never evolved past Puccini and she spends most of her time immersed in any century before the 20th.

-

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter Weekend

Two quick and easy seasonal asparagus recipes to try this Easter WeekendAsparagus has royal roots — it was once a favourite of Madame de Pompadour.

By Melanie Johnson

-

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtower

Sip tea and laugh at your neighbours in this seaside Norfolk home with a watchtowerOn Cliff Hill in Gorleston, one home is taller than all the others. It could be yours.

By James Fisher

-

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?Martin Fone takes a look at the history of London's coalgates, and finds that the idea of taxing things as they enter the City of London is centuries old.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?Final words can be poignant, tragic, ironic, loving and, sometimes, hilarious. Annunciata Elwes examines this most bizarre form of public speaking.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?Tales of swashbuckling pirates have entertained audiences for years, inspired by real-life British men and women, says Jack Watkins.

By Jack Watkins

-

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?The history of the Olympics is full of curious events which only come to prominence once every four years. Martin Fone takes a look at one of the oddest: race walking, or pedestrianism.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylight

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylightMartin Fone tells a tale of sunshine and tax — and where there is tax, there is tax avoidance... which in this case changed the face of Britain's growing cities.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?A completely fair game of chance, or an opportunity for those with an edge in human psychology to gain an advantage? Martin Fone looks at the enduringly simple game of rock, paper, scissors.

By Martin Fone

-

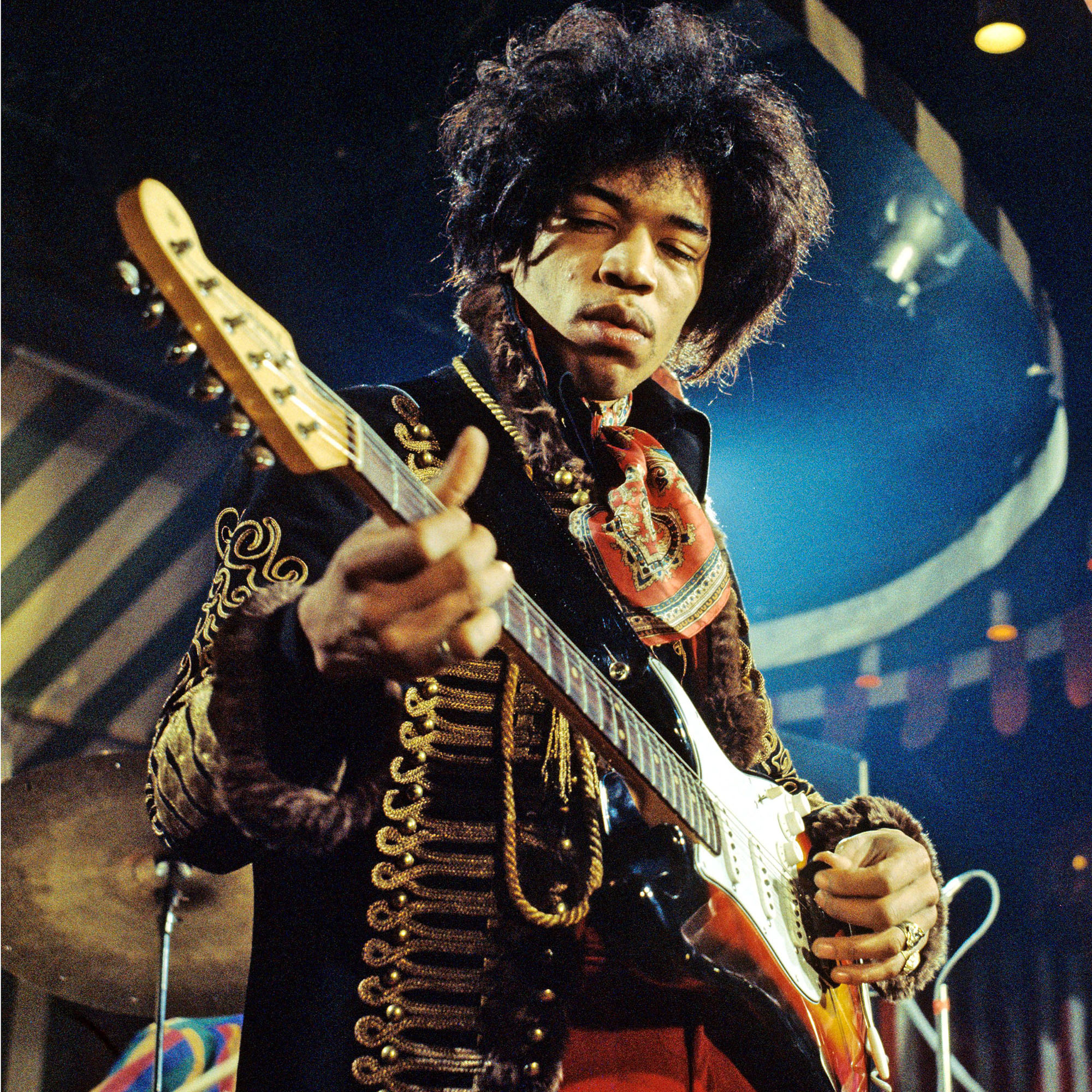

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?In days gone by, left-handed children were made to write with the ‘correct’ hand — but these days we understand that being left-handed is no barrier to greatness. In fact, there are endless examples of history's greatest musicians, artists and statesmen being left-handed. So much so that you'll start to wonder if it's actually an advantage.

By Toby Keel

-

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?

Curious Questions: Why does our tax year start on April 6th?The tax-year calendar is not as arbitrary as it seems, with a history that dates back to the ancient Roman and is connected to major calendar reforms across Europe.

By Martin Fone