Curious Questions: Why are Christmas cracker jokes so corny?

With the dust having settled on Christmas, there is only one question left to ponder: why are the jokes in crackers so intentionally bad? Martin Fone explains all.

Shaped like a sweet wrapping, it is a segmented cardboard tube enclosed in colourful paper. These days, it is regarded as an essential component of the Christmas dinner, enabling us to engage with a fellow diner in that curious ritual of pulling it apart. A satisfying small bang, the result of friction on two shock-sensitive, chemically impregnated areas on a thin cardboard strip, accompanies the sound of ripping paper. The person with the largest portion scoops the prize, usually a coloured paper hat, a small toy or object, and a corny joke.

When to pull a Christmas cracker is a matter of some debate. It must be galling for someone who has spent hours preparing the main course and choreographed its serving to perfection to see their guests letting the fruits of their labour grow tepid as they pull their crackers. Some etiquette experts suggest that the correct time to pull a cracker is either when the main course has been completed or after the dessert. Whilst this is eminently sensible, frankly, the main course would not taste the same without wearing a paper hat.

But what of the jokes? Originally manufacturers included poetry or sayings, but rib-ticklers were first included in Totem Tom-Tom crackers in the 1920s — more on those later — and by the 1930s they had replaced verses and mottos as a matter of course.

They are irredeemably corny and cringeworthy, guaranteed to provoke a chorus of groans from the assembled company.

But why? Why do they have to be so bad?

It is all down to the audience. The assembled company around a Christmas table is made up of all ages and sensibilities. What was needed was a joke that everybody would understand, would elicit a titter or groan, and not cause offence.

These strictures left the joke writer with little option but to craft plays on words and attempts at humour that even an easy-going sub-editor would be tempted to excise from a child’s joke book. Mind you, the quality of the romantic verses they replaced was not high; a theatre critic for the Westminster Gazette was moved, in 1906, to describe a particularly shoddy piece of drama as “not up to the standard of cracker poetry”.

Sign up for the Country Life Newsletter

Exquisite houses, the beauty of Nature, and how to get the most from your life, straight to your inbox.

You search in vain for pearls in a cracker. Once you're past the age of 8, that is.

The origin of the cracker can be traced back to an idea brought back to London by sweet manufacturer Thomas Smith after a trip to Paris in 1847. He was intrigued by the Parisian bon-bon, a sugared almond wrapped in pretty tissue paper with a twist either side of the central section. This was something, he thought, that would pique the interest of his gentlemen customers looking for a little something to give to their lady friends, particularly in the Christmas season. Initially, his offering was a sugared almond with a love motto wrapped together in a central chamber with two twisted ends, but by 1849 the almond had given way to small gifts such as toys, trinkets or jewellery.

Whilst sales were encouraging, Smith was on the look-out for ways to make his product more appealing. The story goes that in the 1850s he became fascinated by the snap and crackle that his hearthside fire was making and wondered whether he could replicate that commonplace sound of a Victorian living room when the paper wrapping was torn apart. The sound of a small explosion would surely cause delight and amusement and make sales go with a bang.

After a period of development and experimentation, Smith launched, in 1861, what he called “Bangs of Expectation”, an early form of cracker. They were also known as cosaques, probably after the Russian Cossacks, encountered during the Crimean War and renowned for firing their rifles up in the air while riding their horses. At the same time, the basic cracker shape we would recognise today was established.

Although he took out a patent, Smith’s innovation soon attracted imitators, including another London ornamental sweet-maker, Gaudente Sparagapane. His company, established in 1846, a year before Smith’s, claimed in its advertising to be “the oldest makers of Christmas crackers in the United Kingdom”. Whether Sparagapane beat Smith to the draw or not, Smith is generally credited with inventing the cracker.

After Smith’s death in 1869, the business passed to his sons, Thomas Junior and Walter, who moved premises from Clerkenwell to 65-69 Wilson Street, near Finsbury Square. In March 1889 disaster struck when a fire broke out in the building, but within nine months it was back in business, employing, according to a contemporary newspaper report, 2,000 people including four hundred female workers, producing 112,000 boxes of crackers a year. As now, many of the gifts inside were imported from the Far East, although then from Japan rather than China.

Crackers were not just for Christmas. Tom Smith and Company introduced a range of themed crackers to celebrate major state occasions, military campaigns, and technological innovations such as the wireless. Crackers were made in support of the Suffragettes, ironically Sparagapane’s daughter, Maud Sennett was a leading light in the movement. Stage shows, and theatre and film stars also received the cracker treatment.

There were Charlie Chaplin themed crackers and perhaps the most extravagant was The Totem Cracker, launched in 1927, to cash in on the Totem Tom-Tom dance craze, spawned by the 1925 musical, Rose-Marie. For the sum 34 shillings you received a dozen crackers complete with Totem-Pole Girl headdresses, musical toys, imitation jewellery and jokes. Bizarrely, there were even crackers aimed at bachelors and spinsters, whose gifts included wedding rings and false teeth, a case of hope mixed with realism, perhaps.

Paper hats were introduced in the 1890s by Walter. Smith’s crackers even found royal favour, receiving their first Royal Warrant in 1906 from the then Prince of Wales. Now part of the Design Group, Thomas Smith’s company still produce crackers for the royal family. They have also left their mark on the city’s landscape. The fountain to be found in Finsbury Square was erected by the Smith brothers in memory of their mother, Martha. If you look closely at the pediment, there is something which looks suspiciously shaped like a cracker.

Is there a way to pull a cracker that guarantees you have the largest portion? According to defence technology experts, QinetiQ, the key is to ensure that the end you have grasped is lower than the other person’s so that it is tilting towards you, use a firm, two-handed grip, pull the cracker slowly and steadily, and do not twist it. Let us know if it works.

Whether that technique was deployed by any of the 1,478 people who participated in the world’s largest ever Christmas cracker pull, organised by Honda Japan at the Tochigi Proving Ground on October 18, 2009, I cannot say. Pulling the cracker made by the parents of children at Ley Hill School and Pre-school in Chesham on December 20, 2001 would have presented a challenge. At 63.1 metres in length and 4 metres in diameter, it holds the record for the world’s longest cracker. It must have made quite a bang.

Curious questions: Who was the first person to receive the Victoria Cross?

Martin Fone retraces the history of the order and discovers the stories of its early recipients.

Curious Questions: What is a 'doubly-thankful' village — and how did Upper Slaughter become one?

Martin Fone examines the (sadly rare) phenomenon of the parishes who erect memorials not to the fallen, but to those

Credit: Getty

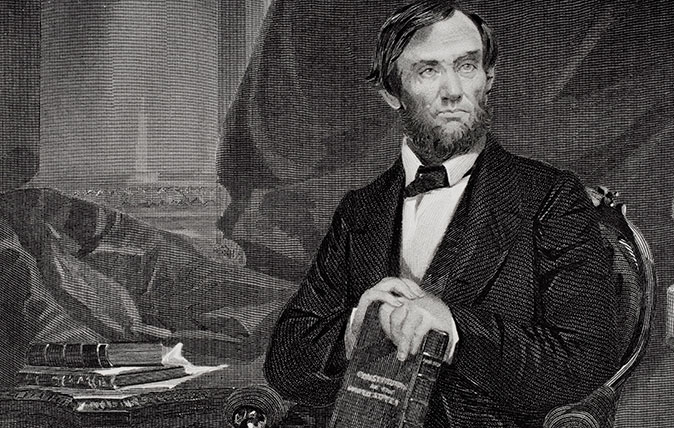

Curious Questions: How did Abraham Lincoln come to be the only US president to hold a patent?

Statesman, lawyer, fearless leader – and part-time inventor. Martin Fone looks at one of Abraham Lincoln's lesser-known talents.

Credit: Jamon Iberico

Curious Questions: Do delicious hams from little acorns grow?

Jamón Iberico is undeniably delicious – and undeniably pricey. Martin Fone took a trip to Spain to find out how it

After graduating in Classics from Trinity College Cambridge and a 38 year career in the financial services sector in the City of London, Martin Fone started blogging and writing on a freelance basis as he slipped into retirement. He has developed a fearless passion for investigating the quirks and oddities of life and discovering the answers to questions most of us never even think to ask. A voracious reader, a keen but distinctly amateur gardener, and a gin enthusiast, Martin lives with his wife in Surrey. He has written five books, the latest of which is More Curious Questions.

-

The King's favourite tea, conclave and spring flowers: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 22, 2025

The King's favourite tea, conclave and spring flowers: Country Life Quiz of the Day, April 22, 2025Tuesday's Quiz of the Day blows smoke, tells the time and more.

By Toby Keel

-

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)

London is the place for me* (*the discerning property buyer)With more buyers looking at London than anywhere else, is the 'race for space' finally over?

By Annabel Dixon

-

The Country Life Christmas message by Revd Dr Colin Heber-Percy: ‘The most powerful person in the world’ is not an emperor, high priest or CEO, but a helpless baby in the arms of a loving mother

The Country Life Christmas message by Revd Dr Colin Heber-Percy: ‘The most powerful person in the world’ is not an emperor, high priest or CEO, but a helpless baby in the arms of a loving motherRevd Dr Colin Heber-Percy on how Christmas shows us that ‘the most powerful person in the world’ is not an emperor, or a high priest or the CEO of a tech company, but a helpless baby in the arms of a loving mother.

By Rev Dr Colin Heber-Percy

-

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?

Curious Questions: Did the Victorians pave the way for the first ULEZ cameras in the world?Martin Fone takes a look at the history of London's coalgates, and finds that the idea of taxing things as they enter the City of London is centuries old.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?

Curious Questions: What are the finest last words ever uttered?Final words can be poignant, tragic, ironic, loving and, sometimes, hilarious. Annunciata Elwes examines this most bizarre form of public speaking.

By Annunciata Elwes

-

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?

Curious Questions: Why do we still love pirate stories, 300 years on from Blackbeard?Tales of swashbuckling pirates have entertained audiences for years, inspired by real-life British men and women, says Jack Watkins.

By Jack Watkins

-

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?

Curious Questions: Why is race walking an Olympic sport?The history of the Olympics is full of curious events which only come to prominence once every four years. Martin Fone takes a look at one of the oddest: race walking, or pedestrianism.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylight

Curious Questions: Where does the phrase 'daylight robbery' come from? It's literally about the theft of daylightMartin Fone tells a tale of sunshine and tax — and where there is tax, there is tax avoidance... which in this case changed the face of Britain's growing cities.

By Martin Fone

-

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?

Curious Questions: Is there a way to win at rock, paper, scissors?A completely fair game of chance, or an opportunity for those with an edge in human psychology to gain an advantage? Martin Fone looks at the enduringly simple game of rock, paper, scissors.

By Martin Fone

-

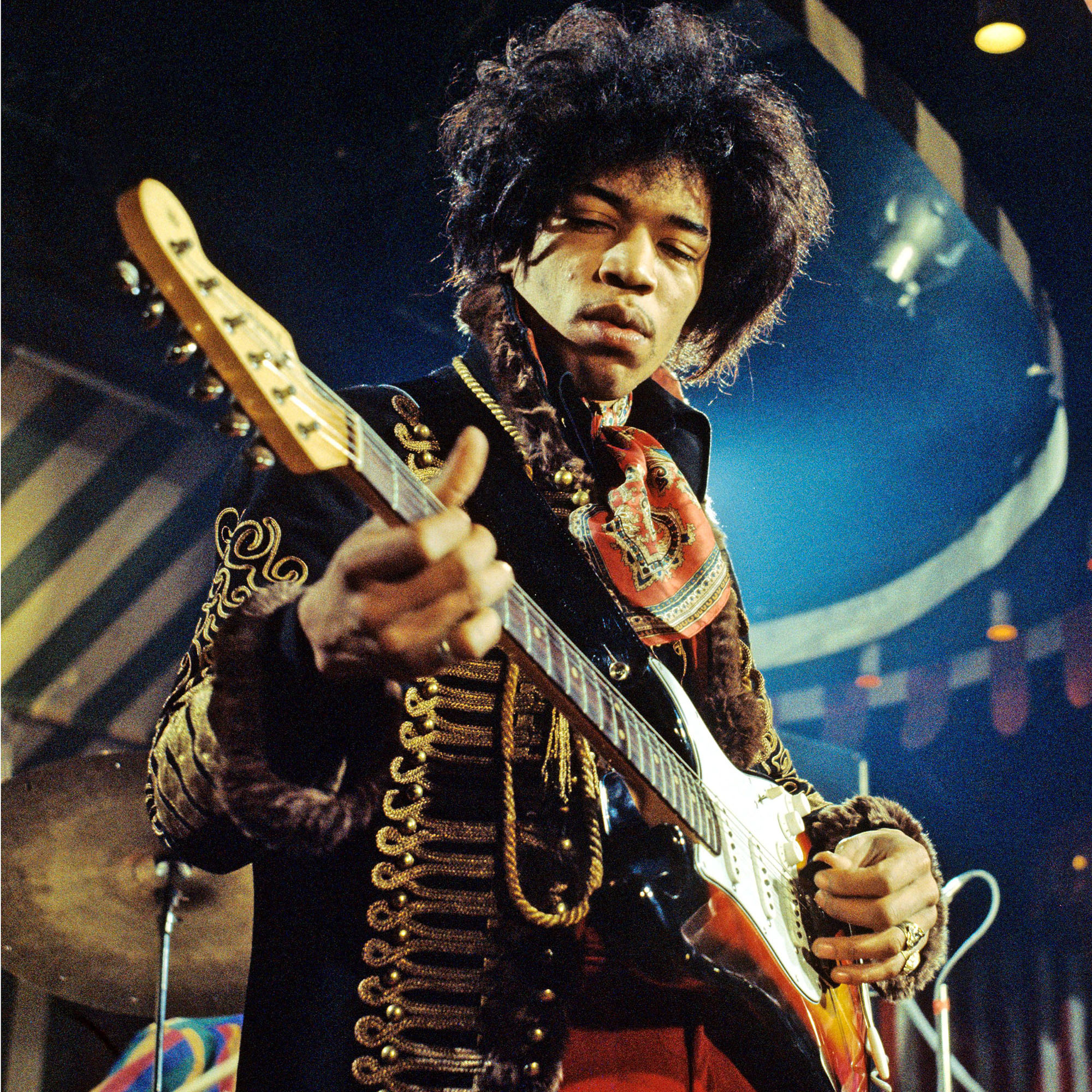

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?

Curious Questions: Is being left-handed an advantage?In days gone by, left-handed children were made to write with the ‘correct’ hand — but these days we understand that being left-handed is no barrier to greatness. In fact, there are endless examples of history's greatest musicians, artists and statesmen being left-handed. So much so that you'll start to wonder if it's actually an advantage.

By Toby Keel